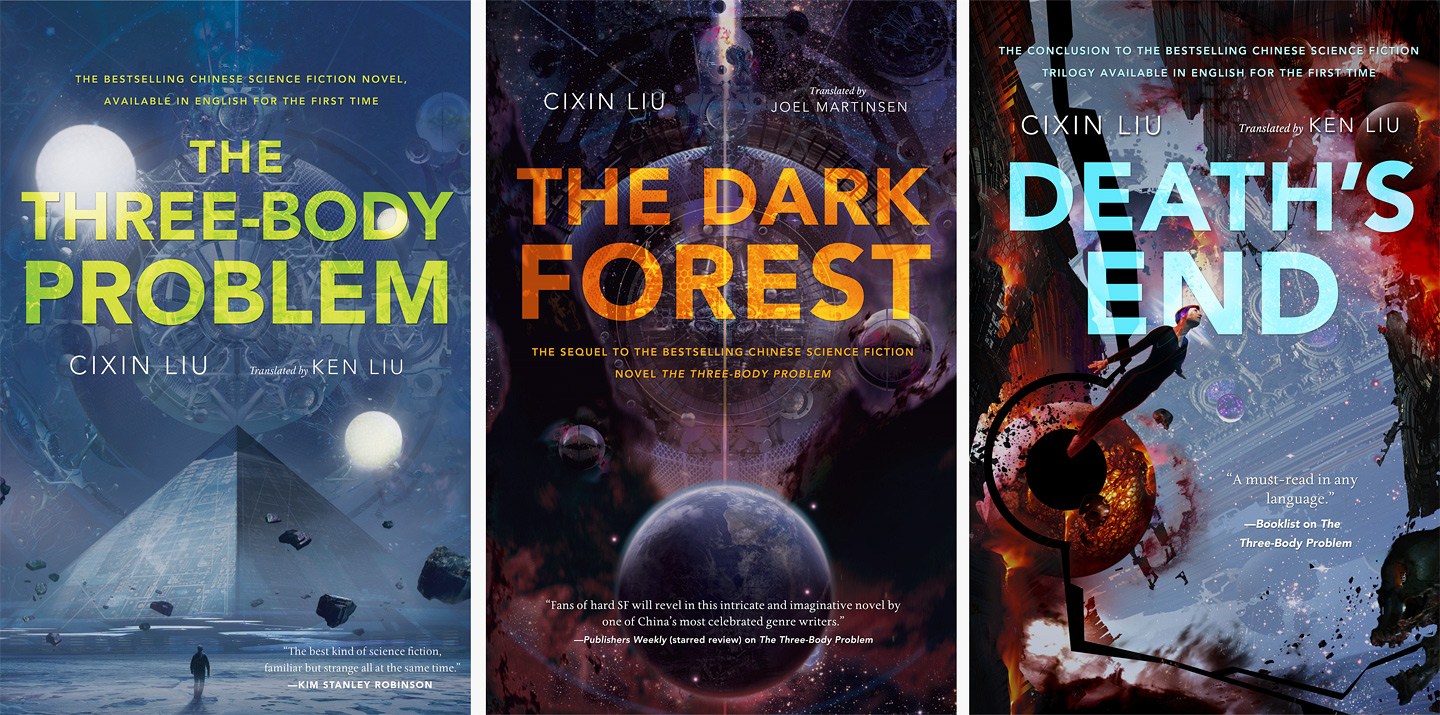

Death's End is the third book in Cixin Liu's universe-spanning trilogy, which began with an ominous first contact in The Three-Body Problem and turned into an outright alien invasion in The Dark Forest. Theodore McCombs, who wracked his brain over The Three-Body Problem for Fiction Unbound last May, and Mark Springer, who explored The Dark Forest in October, now ask each other whether humanity ever could, or ever should, achieve Death's End. Warning: major spoilers ahead!

Mark Springer: Let’s get this out of the way right up front: the Three-Body trilogy (officially Remembrance of Earth’s Past, but no one knows what I’m talking about when I call it that) is sprawling, ambitious, and awesome. It is, quite simply, long-form storytelling at its best. Individually, each novel is an engaging masterwork of modern science fiction. Together, the novels present an ambitious thematic progression that takes the form of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis.

Theodore McCombs: The thesis introduced in The Three-Body Problem, the trilogy’s first book, can be handily summed up in a line from one of its last chapters: You’re bugs! The cosmos is not, apparently, an orderliness gradually unveiling itself to humanity’s delight, and the dream of individual self-fulfillment looks embarrassingly naive. What we see as our patrimony—a temperate Earth, a rational universe, a stable society—is really just a pocket of luck.

Four light-years away, the Trisolarans have evolved in a trinary star system whose complex, unpredictable orbital pattern (the titular three-body problem of classical mechanics) makes the system’s lone planet unbelievably harsh and uncertain. Their culture is ruthlessly utilitarian, because they’ve had to progress in an environment in which no one knows, no one can even guess, whether any sun will come up tomorrow or the sky stay dark for a hundred years. The moments of stability, when civilization can flourish and advance, are lucky exceptions to the chaos. Earth, with its stable solar orbit and sentimental humans, is ripe for invasion: our own luck is about to run out. But Liu’s references to China’s Cultural Revolution and environmental degradation emphasize that this kind of instability isn’t really so unfamiliar, and his thesis isn’t so speculative as we’d prefer.

MS: In The Dark Forest, the trilogy’s middle act, the nature of the universe is revealed to be even darker and more brutal than humankind’s encounters with the Trisolarans in the first book suggested. Advanced civilizations abound in the cosmos, perhaps on the order of millions or billions, but don’t expect them to sign on to the United Federation of Planets. Like the illusions of benevolence and stability we perceive in the universe, our Enlightenment ideals also prove to be quirks of a unique perspective that emerged out of our species’ unusual pocket of good luck, as dependent on initial conditions as the irresolvable three-body problem itself. Empathy, cooperation, and individual dignity may be self-evident to us, but in the vast, dark emptiness of space, survival and suspicion are the true prime directives.

And yet, surprisingly, as The Dark Forest carries humankind inexorably toward annihilation by the Trisolarans, the novel’s hero, Luo Ji, discovers that the antithesis to You’re bugs! is … love. Or rather, love backed by the plausible threat of mutual assured destruction. In humanity’s darkest hour, Luo Ji finally grasps the truth of cosmic civilization, and miraculously forces a truce between Earth and the Trisolarans.

TM: Finally, in the trilogy’s synthesis, Death’s End recalibrates the miracle of Luo Ji’s success to the hostility of the universe. Yes, there are exceptional people who make a difference, but it’s limited. The novel’s heroine, Cheng Xi, is a brilliant and humanitarian scientist from our present who arrives in Earth’s future, in the midst of Luo Ji’s détente with the Trisolarans. She is chosen to take over from Luo Ji as “Swordholder”—to hold the doomsday button that will destroy both civilizations. Her decision within this role brings untold disaster; and yet, she gets another chance to save humanity when her company starts to develop light-speed travel. Again, she makes an important choice, but one with bitter, terrible consequences.

Our other hero, Cheng Xi’s old friend Yun Tianming, is probably the most extraordinary person in the history of Earth: he becomes a brain shot into space to spy on the Trisolarans (trust me, it’s awesome), and his ingenuity, courage, and diligence create an extraordinary opportunity for Earth to secure itself in the dark forest; but again, there’s only so far that security can go. The house always wins. But isn’t that true of every species, every planet? There is no cheating death, not for even the most ruthless civilization.

MS: Throughout the trilogy, and especially in Death’s End, Liu is unsentimental in his depiction of the conflict between human idealism and the cold, kill-or-be-killed calculus of the dark forest. While he acknowledges that ideals like compassion and cooperation have served our species well, if inconsistently, within the short timespan and narrow scope of life on Earth, Liu has no illusions that we should expect other intelligent life to share our values, or even to regard them as meaningful.

This conflict imbues the trilogy with a moral complexity that offers little comfort to our earthbound sensibilities. In a crowded universe where life is always expanding but the total amount of matter remains finite, the outcome of a decision can be morally right, as judged by human ideals, and yet lead to unimaginable catastrophe, as Cheng Xi discovers not once but twice. If standing firm on your principles results in the end of human civilization as we know it and the destruction of the Solar System, what good are those principles?

TM: That taps one of the richest veins in literature, doesn’t it: What good is a moral woman (or man or ooloi or desiccated Trisolaran blob) in an immoral world? From Billy Budd to Chinatown, we keep asking why we’re so fascinated with goodness when the rest of the world ignores it so aggressively. Liu calls the question on the grandest scale, because the meaning of “charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence” deserves to be asked against its true backdrop—the entire spatial and temporal breadth of the universe.

Forget it, Jake—it’s the Dark Forest.

MS: For much of Death’s End, Liu seems to imply that humanism is incompatible with survival in the dark forest of the cosmos. And yet, the human race does escape annihilation. Cheng Xi encounters one of the survivors, a scientist named Guan Yifan, on a planet far from the Solar System, where she learns that Galactic humans have successfully adapted to the harsh realities of the universe, becoming active participants in a grand cosmic scheme that Solar System humans never could have imagined. With this great synthesis comes great responsibility, Guan Yifan tells her: “Things like the fate and goal of the universe used to be only ethereal concerns of philosophers, but now every ordinary person must consider them.”

TM: I love that; it feels timely. As I’ve written elsewhere, today’s moral challenges are collective: populations do good or evil en masse, as an aggregate of individual, marginally impactful choices like biking to work or buying health insurance. We need writers like Liu who can challenge us into that new kind of moral calculus.

MS: It’s not revealing too much to say that Cheng Xi’s idealism is finally vindicated. As the universe itself approaches death, millions of civilizations believe they have found a way to survive the collapse by creating untold numbers of mini-universes in the antimatter space surrounding the so-called great universe. The hope is that the great universe will be reborn in a new Big Bang, and the inhabitants of the mini-universes can re-enter the new great universe during its Edenic Age.

But there is a catch: the great universe has lost too much mass because the Escapist civilizations have siphoned off matter into their mini-universes. Instead of collapsing to be reborn, the great universe will continue to expand until it dies a slow, irrevocable death; the mini-universes will die too. Here, at the end of the cosmos, as on Earth tens of billions of years earlier, the logic of the dark forest is inverted: suspicion and self-interest have lost their power to sustain life; only cooperation and self-sacrifice can reboot the universe.

Life, the universe, and everything? (Photo of the galaxy Centaurus A, taken by the Hubble telescope.)

TM: So much of Death’s End, even its title, is driven by mortality and our fear of mortality, but by the end Liu captures profoundly the pathos and beauty of an ending. Stars die. Dimensions die. Even the universe itself has its death. Only those who witness the end have to confront that kind of enormity, but Liu brings us all to the brink, and it’s a sublime catharsis. I finished Death’s End in January, contemplating Trump’s inauguration and, as I saw it, the loss of our best opportunity to keep Earth habitable, at least as far as we understand habitability. I hoped I’d never have to psychically prepare for the mass extinctions and outsized human tragedy that I may well witness in my lifetime; but someone, eventually, was always going to have to look at the end. Not that we should all stop trying and turn morbid, but there is grace in acknowledging terminality (Earth included) as the universe’s truest constant.

MS: Peering into the void isn’t easy. As a species, we are the product of billions of years of evolution shaping genes in a relatively stable, reasonably hospitable environment—a deep historical and biological legacy that literally determines how we experience and interpret the universe. Like the Trisolarans and every other sentient low-entropy being, we are children of timing and geography: preconditions beget preconceptions.

One of the motifs running through the trilogy is how difficult it is for human beings to think beyond our frame of reference, whether as individuals or collectively as a species, and how dangerous it is when we refuse to acknowledge the inherent limits of our perspective. From the beginning of The Three-Body Problem to the final pages of Death’s End, Liu’s characters are repeatedly frustrated by their preconceptions as they struggle to learn more about the universe. More often than not, these frustrations get dismissed or rationalized, and the opportunity to transcend the terrestrial frame of reference is squandered, with humbling (and usually tragic) consequences.

Cixin Liu, China's Arthur C. Clarke. (Or is Clarke the West’s Cixin Liu?)

TM: Liu captures the thrill and frustration of pressing against that limitation in the Yun Tianming sequence. Earth wants to plant a spy in the Trisolaran fleet before it reaches Earth: it’s a long shot, but if they can propel a hibernating human at the fleet at 1% of the speed of light, the Trisolarans will hopefully intercept the capsule and revive the human for study (if they don’t vivisect him). As Chen Xi’s team runs into a devastating succession of logistical obstacles, the plan gets weirder and more superb: they will accelerate the capsule with a radiation sail and a string of nuclear bombs detonating behind it; they will flash-freeze the pilot in order to shed the heavy hibernation equipment; they will only send a brain, in the faith that the Trisolarans will have technology to provide Yun some sort of revived life. You feel the tension and vertigo of humanity working outside its frame of reference, barely peeking outside of it, always on the brink of failing totally or evolving an order of magnitude further.

What was your favorite set piece, Mark? For me, the opening sequence in Constantinople was as perfect a beginning to this trilogy’s third book as one could hope for. In 1453, the city is about to fall to the Turks: a reminder that the Trisolarans’ invasion of Earth is only a difference of scale. One woman, the Luo Ji of her time, offers an extraordinary hope of salvation, having figured out how to move through a shard of four-dimensional space passing through Earth (and the city) at that time. But her seeming magic is only a matter of luck, and temporary luck at that, as the shard passes on its way and Constantinople meets its doom.

MS: The book is full of unforgettable moments. One that continues to haunt me is Guan Yifan’s journey into four-dimensional space, and his encounter with the Ring, a tomb left behind by an extinct race of four-dimensional beings. Liu’s descriptions of four-dimensional space are staggering in their own right, but it is Guan Yifan’s conversation with the Ring’s artificial intelligence that gives me chills every time I read it. The Ring’s cryptic answers to Guan Yifan’s questions hint at hidden, terrifying details of the universe that will become clear only later, details so far beyond human understanding that at first they seem to be riddles, rather than truths. The scene ends with the Ring decaying into three-dimensional space, its higher-order structures annihilated in a massive release of energy. Everything about this is sublime, and it provides a prefiguring vision of the fate that eventually befalls the Solar System.

With all this talk of death and loss and the end of the universe, it would be easy to assume that Death’s End is a hopeless story. Granted, it can appear that way from our earthbound perspective. But, as I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog, there are different kinds of hope, and some are more profound than others. Liu’s conclusion to his masterwork trilogy is hopeful in a challenging way. It asks that we set aside our preconceptions and our false hopes, the ones that misrepresent the nature of the universe and our place in it, the ones we turn to for reassurance, the ones that promise we will never die. Only then can we transcend our settled perspectives and discover what we might become. Only then can we truly participate in the story of the universe. Only then will our light be remembered.

Cixin Liu, Death’s End, English translation by Ken Liu. New York: Tor, 2016.

!["Dark Matter" [Spoiler] Review: Blake Crouch’s Science Fiction Thriller Delves into the Multiverse](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5495fc96e4b0d669a5b4ba80/1510258393943-UIS2LSD6OMI3B3X9E0KB/Dark+Matter+2.jpeg)

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.