I have owned a couple of copies of Stephen King’s Danse Macabre. It’s one of my favorite books, though I don’t suppose I’ll ever read it. When I plucked it from a library shelf and flipped through its chapters one Saturday morning in my late teens, the idea of 500 hard cover pages listening to King expound on the horror genre did not appeal to me. But before I snapped it shut for good, I landed on the appendices. A few days later I was back with a pocket full of change. Thanks to the copier in corner, now those appendices were mine for 5 cents a page. They were just the treasure I was hungry for. They were lists.

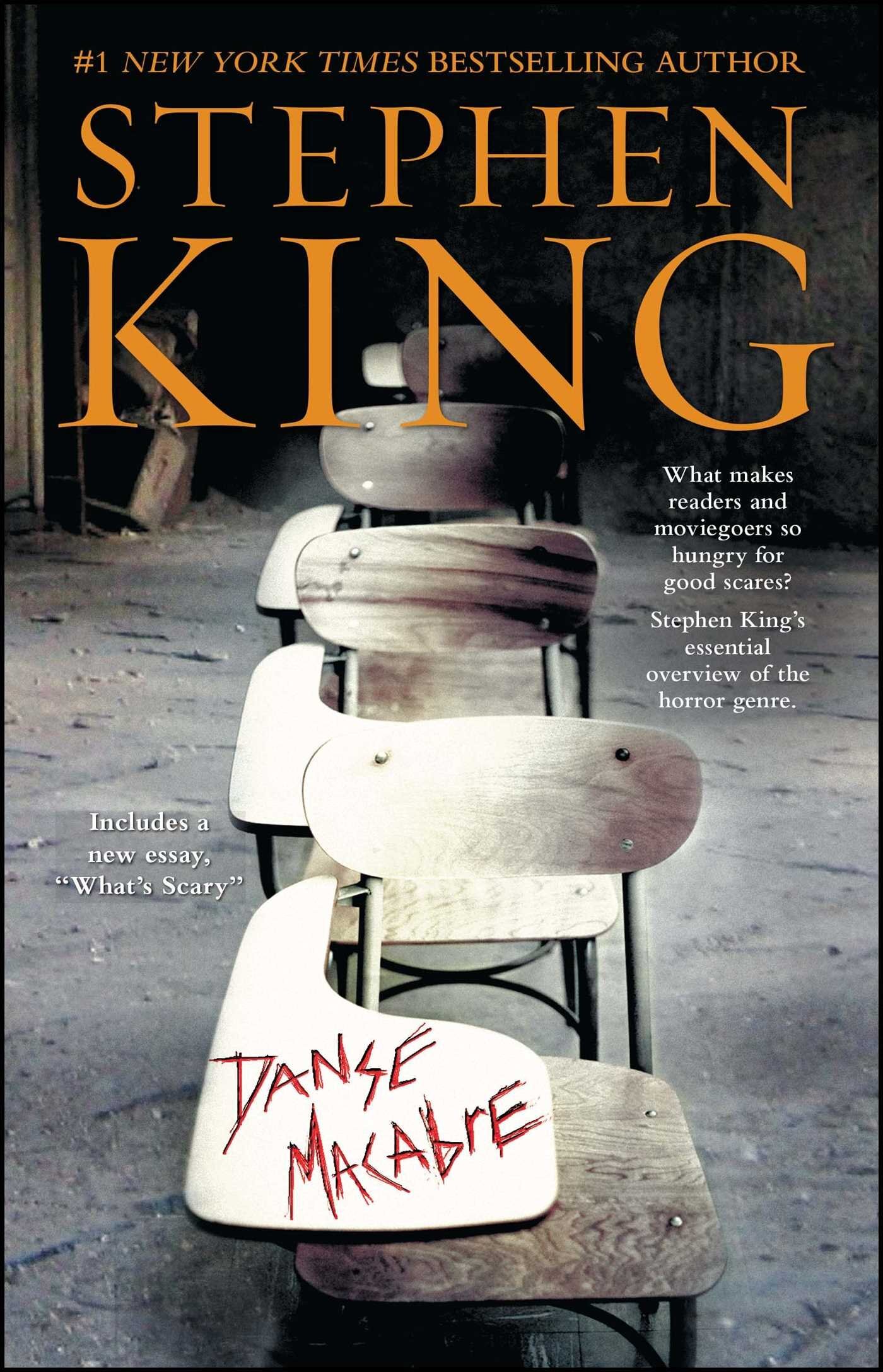

Danse Macabre, Stephen King

These were the horror films and novels that Stephen King thought were the best and most important the genre had produced so far. And he seemed like he would know. Those photocopied pages kept me in recommendations for a handful of summers. They introduced me to some of my favorite writers. Through them I discovered Jack Finney and Ira Levin; Shirley Jackson and Richard Matheson; Richard Adams’ Watership Down and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. These are big names and I likely would have come across them some other way eventually, but I didn’t need to—I found them here.

I love a good, curated list. There is so much out there to read, and until I get my turn in a time loop, I don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights. A page in my phone’s notes ap is where I horde links I’ve been fed through Twitter. This list of lists includes:

NPR’s 2018 reader poll of 100 favorite horror stories

Thrillist’s 33 best science-fiction novels of all time

Paste Magazine’s 100 of the best horror comics of all time

And even

Martin Scorsese’s list of 85 films every filmmaker needs to see

The best lists aren’t ranked. Rankings are always wrong. Suspiciously, purposefully wrong. One suspects a SEO conspiracy to increase engagement. On the web, all lists are at some level click bait, but I come to these lists to get recommendations, not aneurysms. Save your numbers for bar discussions.

But as a fan of lists (also known as a sucker for lists), I want to share with you just one little ranking. I want to tell you about my number one list. I won’t call it the best list. Just my favorite list.

It’s not ranked itself. It’s not even a normal list. It’s more of a map, with the works laid out in time and space.

Ward Shelley’s History of Science Fiction

First completed in 2009 and updated through a Kickstarter in 2017, this image traces the origins of science fiction from its inklings in mythology and legend to its coalescence in Mary Shelley and on to the modern age of space opera, cyber punk, and too much great television. It even allows for other speculative genres to flirt with and diverge from what is more easily called science fiction. The result is a larval Cthulu of sci-fi recommendations that could net you an unofficial MSF (masters of science fiction).

A hi-res image of the 2009 version is available on Ward Shelley’s website. It’s been my PC wallpaper for at least 6 or 7 years now. You can also buy a large poster of the updated version for $33.95 plus shipping from the same website. I once owned this poster, as well, until it disappeared in my last move. Hopefully, one of the movers was impressed by it enough to take it for his own and is now getting some use out of it. I ordered another one just last week, but haven’t received any word on it, yet, so I can’t confirm what effect supplies or the current pandemic are having on availability. But PayPal took my money, so at least that part is working.

It really is not just my favorite list, but also one of my favorite images. So many titles I’m burning to consume are painted here, writhing in cosmic promise. I’ve stared at it often enough I could have read many of the books it mentions in that time.

Of course, I do more than stare. My current reading pile is inspired by the left side of the image. I’m doing a mini trace of the origins of science fiction, starting with Plato’s Republic, on to Thomas More’s Utopia, and then Robinson Crusoe. This is all just prep for Margaret Cavendish’s Blazing World, which I want to compare to Frankenstein, since these often duel for the title of first science fiction novel.

You could create a dozens of other little journeys or just pick a random title from the right side of the map and find a futuristic thrill. Ward Shelley has here traced the dialectic of wonder. Sure, he’s missed a lot. But he’s hit enough to keep you occupied.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.