We’re all worried about the future. This year two things will happen on November 8th that will inform our futuristic musings: One is the release of Cyber World: Tales of Humanity’s Tomorrow by Hex Publishers. This is their second anthology, and co-editors Jason Heller and Joshua Viola gave the Fiction Unbound contributors a sneak-preview of their reboot of a classic genre, cyberpunk. Here is what we found:

Mark Springer: Cyberpunk, Rebooted

Cyber World starts with a bold proclamation: “Cyberpunk is dead.” So says Joshua Viola in his introduction to the collection. The claim seems convincing at first. After all, how could a subgenre of science fiction so ambivalent about technology survive in an age so absolutely dependent on technology? Surely the wonders of the early 21st century have laid to rest the anxieties that so troubled William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and the rest of cyberpunk’s pioneers. Instead of dehumanizing us, instead of disenfranchising us, technology, especially digital technology, has changed the world by empowering us. We are more connected than ever before, we have more access to information than ever before, we have more gadgets than ever before—and we can’t live without any of it. We have accepted the digital revolution, embraced it, assimilated it. We love this brave new world. Rest in peace, cyberpunk. Thanks for giving us Neuromancer, Snow Crash, Blade Runner and The Matrix (the first one, not the sequels).

But if cyberpunk is dead, what’s the point of Cyber World? Are we in for a revival of the naïve techno-utopian fantasies of the 1940s and 50s, stories long on optimism and short on nuance?

Thankfully the answer is no. While Viola and co-editor Jason Heller are eager to move sci-fi’s ongoing conversation about the costs and consequences of technology beyond cyberpunk’s dated tropes, Cyber World turns out to be an upgrade for the genre (or a reboot, in the parlance of our times), rather than an obituary. The upgrade is welcome and necessary, because the triumph of the digital revolution hasn’t settled cyberpunk’s underlying questions about humanity’s fraught relationship with technology. Instead, these questions, and their accompanying anxieties, have only become more central to our lives, and more urgent. For example:

What happens when we cede our decisions to algorithms over which we have no control? “Panic City,” by Madeline Ashby, imagines an underground city run by an autonomous, self-aware artificial intelligence. The city is an ark of sorts, built to protect the super-rich Elect and their descendants (and their servants and support staff) from whatever misfortunes have befallen the plebeian surface dwellers “upstairs.” Like HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the city’s AI has complete control of its environment, knows more than its masters, and solves unforeseen problems with a ruthless logic that leaves no room for argument.

“What are you doing, Dave?” Whether we know it or not, the algorithms that run our lives aren’t always aligned with our best interests.

Are we willing to sacrifice the future for technological advances today? Every technology has environmental costs. We know this, and yet we continue to burn fossil fuels, we produce plastics and thousands of toxic chemicals, we pollute our air and water and soil, all so that we can watch cat videos on our smartphones whenever the mood strikes. Paolo Bacigalupi’s “Small Offerings,” in which prenatal care has evolved in response to an increasingly toxic environment, reminds us that the costs of the present will be borne more by our children than by us.

What do we lose when we give up our privacy? In the age of surveillance capitalism, this question, like the concept of privacy itself, feels quaint. Privacy is a small price to pay for getting free turn-by-turn navigation in Google Maps and endless distractions on social media. We’ve given up our digital selves willingly, and we couldn’t get them back if we wanted to; digital surveillance is here to stay. The natural next step is actual surveillance, 24/7, public and private, as in “Darkout,” by E. Lily Yu. The initial discomfort you experience broadcasting your life to anyone that wants to watch will fade as soon as you get hooked watching someone else’s life. Once the panopticon is up and running, you won’t be able to look away.

CS Peterson: The Cyber World CD and an Interview with Jason Heller

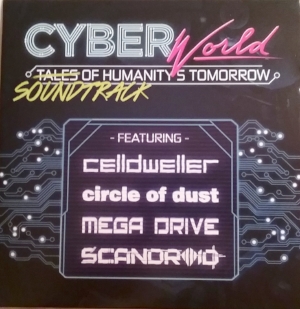

The folks at Hex have released a CD to go with the anthology: Cyber World: Soundtrack of Humanity’s Tomorrow. It is the perfect music to have in the ambient environment as you dip into the stories. The CD features Celldweller, Mega Drive and Scandroid. I don’t pretend to have any expertise in the music of the cyber ’80s, aside from having it as the background to my late-teen life. But the sounds of these bands brought back wave upon wave of nostalgia.

I stood, once again on the pedestrian pavement of Piccadilly Circus, wearing high-heeled black leather slouch boots and eating a cream puff purchased with the first fruits of my nascent street performing. I was staring at an elaborate window display of the newest technology: compact discs. They were threaded on thin neon tubes, lit up like light sabers, and twinkling like the future. A boy with blond dreadlocks passed behind me, the voice of Boy George blaring on his boombox.

A few weeks ago I sat down with Cyber World co- editor Jason Heller to talk about the formation of the anthology.

CS Peterson: So when did this project really take off for you?

Jason Heller: The thing that really brought it all together was Nisi Shawl coming onboard. She is a fabulous writer and was someone who began writing cyberpunk in the late 80s and early 90s. I emailed her and she said, “I actually have a story that would fit the anthology that I just finished writing, and I hadn’t thought about what I was going to do with it yet—do you want to take a look at it?” And I looked at it and it was perfect. For the most part I was on the front line, acquiring the stories, doing the first round of edits. I sequenced the stories, which to me is a very important thing.

CSP: Could you talk about that for a little bit? What kind of considerations do you put in to sequencing?

JH: I’d never done this before, but it is something I think about all the time from being in bands for so long and being a music journalist.

CSP: Did you think about it like the order of songs on an album?

JH: Yes. There are infinite variations, there’s no one right way. But you can tell when it’s just haphazard and when there’s a kind of flow to it. There are two stories in the book that open with someone walking into a shop. I didn’t want them next to each other, but walking into a shop—that actually feels like a first story in a book. Entering a world. Someone walks into a shop and what are all these weird things in here? You’re gradually going to find out. It’s a neat metaphor for the book itself, so I wanted one of those stories first.

I wanted it to build to sort of a climax—to almost follow a kind of story arc where there was going to be a climactic story and a resolution, and I wanted to build up intensity and length. I wanted a couple of the meatier stories length-wise to be right where the climax of a novel would be. Then at the very end—the last two stories—one of them is by a Canadian author named Minister Faust, and then this last one is by a Texan author named Darin Bradley. Minister’s story is totally bizarre. It is very reality warping, totally mind blowing. It takes place in Africa, and there are giant weird crystalline insects. It’s a bizarre story that messes with the infrastructure of time. It’s very Philip K. Dick in that way. The end of the story actually has a bit of deconstructed typography. The text falls apart at the end—it gets very meta.

CSP: It really does look like it’s falling right off the page.

JH: It literally disintegrates at the end. And then Darin Bradley’s story at the end is the denouement. It is a post-modern story about the inner workings of reality, kind of like what goes on behind the walls of what we can see and hear. It’s also metafiction in the sense that it comments on fiction’s own structure. The story refers to itself as a story, talks about the whole idea of what a story is supposed to accomplish, the rules that a narrative is supposed to have and how this story is breaking it. This story deconstructs everything, deconstructs itself in the end. Then it goes into this very quiet weird story that references everything that’s gone before, consciously, even the title: “How Nothing Happens,” is a commentary.

Jason Heller, editor of Cyber World. At MileHiCon, Denver, October 2016. Mugshot by Lisa Mahoney.

CSP: And the author does all this quickly. That story is really short.

JH: It makes a good finish, leaves you with the flavor of the anthology as a whole. Those last two stories together actually make a comment about cyberpunk. They make a comment about the rules and the tropes that we accept as people who write and edit fiction. To what extent can we or should we tweak or break those? To what extent can we adhere to them, play with them or even exist within them?

Gemma Webster: What Is Truth? What Is Real?

This genre lends itself well to examining the notion of self and our experience of reality. Which is really speaking to the nature of truth. Put on your headset, dive deep and don’t forget your parachute pill.

“The Mighty Phin” by Nisi Shawl

Phin is imprisoned on the ship Psyche Moth, whose mission is to settle Amends. She had been a teacher whose subject was considered treason against WestHem, the creator of the ship’s AI, Dr. Ops, where her consciousness has been downloaded. She has lost her body as punishment, but her avatar is an almost perfectly faithful recreation of the flawed body she once inhabited. Except for her feet.

As part of her sentence, Phin meets with the avatar of Dr. Ops, who acts as her psychoanalyst. The precariousness of Phin’s existence is revealed when Dr. Ops falls in love with her and begins to manipulate her avatar-body and her experience aboard the ship, raising questions of consent both physical (sexual and avatar manipulation) and mental (breaking the rules of perceived autonomy with her experience).

“She stared down at her feet. At her tiger toes. Phin’s body was more hers than ever since Dr. Ops reversed the ‘correction’ WestHem had mandated for her syndactyly. Also though, it wasn’t because proud as she’d felt about her ‘deformity,’ that part of her was gone. Along with every other physical thing about Timofeya Phin. Pulled apart by the machines that read her, coded her, entered her into the memory of Psyche Moth’s Dr. Ops.

“The fact that he’d been able to reset her feet to their original version so effortlessly, proved that they weren’t hers. They were his.”

This story reminds me of Octavia Butler’s Dawn: the altering of the body against the will of its possessor. The guardian/wardens who claim to act in the best interest of their wards but are careless with consent. This story goes a step further in removing the boundaries of the physical body but retains the consequences. Can the self exist when it is no longer constrained within the physical boundaries? What are the boundaries when the self mixed and remixed within the virtual sphere?

“Visible Damage” by Stephen Graham Jones

Raz is a hacker for hire, and when his mark, Mark, asks him for an ASCII-graph. Raz is not the type to just get simple images “[sucked] through a filter, filling the shape of a dog with letters-as-shading, numbers-as-eyes, punctuation to show the tail wagging.”

That sort of thing was too easy, Raz is a “server paparazzo.” Mark requests a 722, a pi-maker. To get it Raz will have to dive into the deepest virtual “rabbit hole” to capture this image of a dormant AI. But Raz doesn’t just want the safe image. He wants to see the AI in action. Using old technology to wake a sleeping monster, Raz is courting peril.

“They didn’t dustshelf all those units because they were bulky or because the haptics fed back seizures. They scrapped them because the interface went a smidge too deep. If there’s a glitch on either end, even just a blip, a cough, a hint of the thread starting to unravel, you can get trapped in an infinite regress … you keep cycling waiting for that one variable that can stop the world from sweeping past over and over.”

What is reality, and how do we know when we’re spending so much of our lives in the virtual realms? What do we reach for when we need to pull ourselves out of the abyss?

Sean Cassity: Sometimes There’s a Rainbow While Your House Is Flooding

You don’t start a heavy metal album with a ballad; that’s not what heavy metal is about. But that doesn’t mean you don’t want to slow things down a little here and there. The mellow openings and interludes of “Welcome Home (Sanitarium)” on Metallica’s Master of Puppets as well as “Cemetery Gates” on Pantera’s Cowboys from Hell hollow out space in the middle of the album to echo and amplify the frenzied vibratos that surrounds them.

Matthew Kressel’s “The Singularity Is in Your Hair” functions the same way when it appears six stories into Cyber World. Cyberpunk, almost by definition, carries a dystopian sway in it swaggering journey along technology’s potential. Star Trek’s world of plenty, where you work only because you want to contribute, is not cyberpunk, no matter how many holodecks you install on the Enterprise. Cyberpunk is the pulpy noir of sci-fi, where tawdry escapism into the altered states of VR and pharmaceuticals have lured all or most of the world over to the wrong side of the tracks. So the flare of hope that appears in Kressel’s story is a refreshing reprieve from the gloom, even if it is a false hope that only darkens the shadows of despair in the stories that surround it.

It’s not all love and sunshine, of course. The unnamed protagonist of “The Singularity Is in Your Hair” spends as much time as she can jacked into VR, because in meatspace she has a degenerative disease which has left her a locked in and nonfunctioning. In VR she’s is known as an accomplished artist. She hangs out with a rogue AI named Ashey who sets her up with gigs creating custom VR experiences for well-to-do clients. Ashey is her tutor and friend. Ashey promises her he can upload her into the net someday soon before her body ceases to breathe and pump blood, and she hangs onto that promise. She won’t allow for any hint that VR promises may not come true. Because the alternative is actual reality. In actual reality an alarm rings when it’s time to have her diaper changed. In virtual reality, she can fly when she wants to.

Lisa Mahoney: Mom Doesn’t Know What’s Best

Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Muad-dib Atreides supported by his mother, Jessica. Publicity still from the Universal Studios movie.

A little over a year ago in this blog I bemoaned the lack of mothers in recent speculative literature and movies. Modern writers continue to rely on the old-school fairytale tropes of orphaned protagonists or evil stepmothers, a crutch that shortcuts the creation of poignant characters and magnifies the protagonists’ ordeals. I challenged writers to keep Mom alive and make her a powerful figure, like Jessica Atreides, Paul’s wise, capable and protective mother in Dune.

I have to award the anthologists of Cyber World mother-points for including stories with powerful mothers who break the weak- or absent-mother tradition. Thank you! Mother figures dominate several stories in Cyber World and flip the trope on its head. These mothers are as villainous as any evil step-mom; they are vicious, or self-centered and greedy, or, at best, badly mistaken—Mom definitely doesn’t know what’s best for her kids.

WARNING: Some imprecise spoilers below!

“I kill my mother.” is the opening line of Cat Rambo’s “The Rest Between Two Notes.” (Great opening line!) The fourteen-year-old protagonist produces successive murder fantasies in the office of a psychologist. We soon learn that her wealthy mom is abusive and uses proxies to avoid engaging with her daughter. The daughter’s vengeance shows she will survive and rise above Mom’s tactics.

“Other People’s Thoughts” is narrated by a woman genetically modified by her rich mother who “only wanted someone to be kind to her in a way her own family had not.” When Mom realizes her daughter can read minds, Mom drops her off at an institution to be rewired, but when the procedure fails, she abandons her.

A third story is narrated by an ambitious mother trying to hide her daughter’s disabilities while enriching herself by helping a corrupt corporation. Angie Hodapp’s story is called, ironically, “We Will Take Care of Our Own.” Only after a disgusting display of corporate cruelty does the protagonist bend to public opinion about what’s right, but running for office may still be more important to her than caring for her bed-bound daughter.

In all these stories we find abusive, ambitious or neglectful mothers who damage their daughters, usually by forcing upon them what they think is best. These mothers are not Jessica Atreides, but they are powerful, and they certainly cast long shadows over the lives of the protagonists. Kudos for including stories about characters with big problems who do have mothers (like most of us), and for moving past the orphan trope.

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.