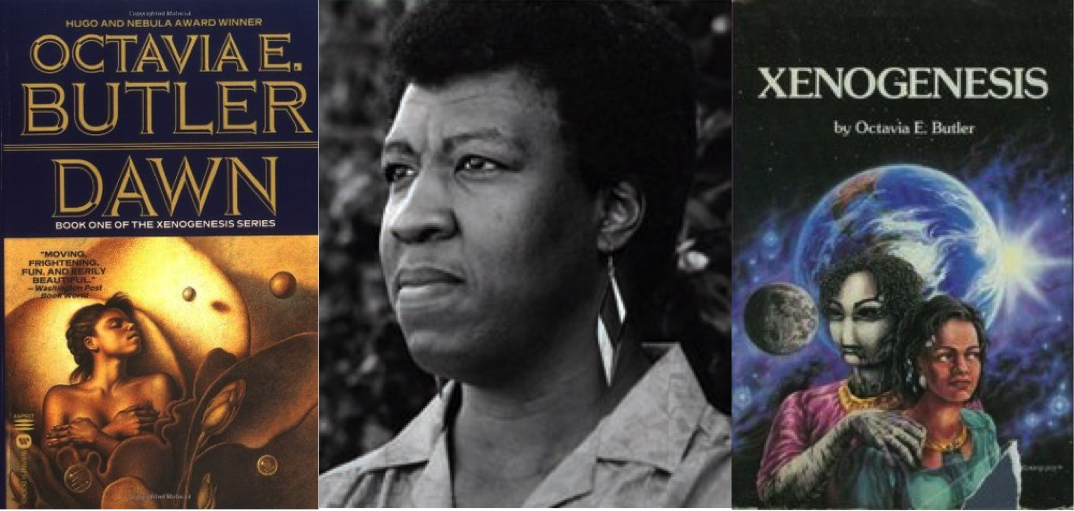

In 1987, Octavia Butler published Dawn, the first book of her Xenogenesis trilogy. (The trilogy was reissued as Lilith's Brood in 2000.) Dawn opens with humanity having all but destroyed itself in nuclear war; one survivor, Lilith, awakens on a spaceship, a captive, patient, and ward of the alien Oankali. The Oankali—a grotesque, tentacled race with a biological talent (and innate drive) for genetic engineering—promise Lilith they mean to restore the human race back to Earth. But there is a price: the new Earth will be home only to the new human-Oankali hybrid race, while the old, pure humanity will effectively end. Unbound contributors Theodore McCombs and Gemma Webster here take a look at Dawn in the first of three Xenogenesis appreciations.

Theodore McCombs: Dawn is now almost thirty years old. I know it’s a revered classic in the sci-fi canon, but I couldn’t find it in any of our local bookstores. When I finally read it, I was more excited over it than any recently published speculative fiction I can remember. What do you see as its relevance today?

Gemma Webster: I’m also working from a used copy. Actually the fully trilogy in one handy book. As far as relevance goes, our technology is catching up to the premise from Swedish researchers editing healthy DNA to a New York fertility doctor who claims to have created an embryo using 3 genetic parents. But Butler is also predicting a conversation about consent that we’re starting to have as a culture only now, in 2016.

TM: The Oankali try to rescue and “cure” humanity of its destructive impulses. They certainly do seem to be coming from a place of genuine benevolence, but they also show a disturbing lack of interest in humanity’s consent. Their programme is obviously good for us, so they see refusal as simple mulishness.

Earlier this month, the Colorado Court of Appeals decided a fascinating and disturbing case in which the state mental hospital sought to administer Depo-Provera, a synthetic hormone, to a hypersexual, schizoaffective inmate to reduce his inappropriate sexual behavior toward staff and other residents. The court ultimately forbade the hospital from this “chemical castration,” observing, among other reasons, that one side effect men experienced was “feminizing” body changes, even to the point of growing breasts. There are some benevolent measures that just carry too high a price, especially when that price is such a profound, involuntary body change. The inmate could have agreed to take the drug, the judges decided, but the hospital couldn’t inject it without his consent—what on earth would they have made of the Oankali’s genetic alterations of Lilith?

GW: Her's is a strange situation certainly. They modify Lilith so that she is able to understand their language, increased her memory and strength (which they believe she’ll need as the first leader of the other people--the Oankali know it won’t go smoothly), and eventually the capacity to open the doors of her own cell. The Oankali see themselves as genetic traders they give of themselves to other creatures they encounter through their travels and in return they take what they can use. It’s funny that it is called trade because trade implies equal exchange and consent. While Nikanj (Lilith’s personal ooloi, the genderless sex of the 3 gendered Oankali) pays lip service to these ideals, the Oankali don’t require even the active participation let alone consent of their trading partners.

This plays out in particular regarding their approach to sexual consent. One of the modifications made to all the humans the Oankali saved/captured is a sort of genetic birth control that can only be surmounted by a three-way with the ooloi as the sexual intermediary. This is also how it works with the Oankalis a male and female partner (all relationships are hetrosexual in Dawn) plus a genderless Oankali called an ooloi (uses the pronoun it). Not all sex between two humans and an ooloi will result in fertility, the ooloi has full control over which sexual episode will end in conception. Actually it doesn’t even have to have three partners, an ooloi and a woman can mate successfully because the ooloi carries the genetic stamp of several other humans inside of it. But the three way is actually the prefered method because the Oankali acting in their benevolent overlord manner thought humans would prefer this.

When Lilith meets and falls for Joseph, Nikanj breaks its promise to Lilith not to interfere. Nikanj inserts itself into Lilith and Joseph’s space and despite protests from Lilith and Joseph about contact, renders Joseph unconscious and proceeds to take over his body and mind. Lilith, being both seduced and disempowered, plugs herself into Nikanj who is plugged into Joseph. The sex is great but is completely non-physical. And of course Joseph didn’t consent. He was essentially roofied.

TM: The ooloi know the human partners feel extreme pleasure from their alien nasty, so they dismiss the humans’ sense of violation and identity crisis as irrational. It’s the same paternalism we see in their plans for a new Earth.

GW: Though the Oankali claim not to lie, they often leave out important information. Lilith would probably not have been a willing participant if she knew that she and Joseph would never want to touch each other again without being connected to Nikanj.

As a self perceived benevolent overlord, Nikanj is caught in an empathy trap: the ooloi know our emotions so well, they start presuming they can make decisions for us. After the sex Lilith confesses her worry about how Joseph will react to Nikanj.

“‘He might…’ She forced herself to voice the thought. ‘He might not want anything more to do with me when he realizes what I helped you do with him.’

’He’ll be angry—and frightened and eager for the next time and determined to see that there won’t be a next time. I’ve told you, I know this one.’”

TM: It mirrors a painful conversation the political Left is having around white allyship—one you and I have both had to participate in—around stepping back, listening from a place of humility instead of power and assurance. White allies, however smart and good-hearted, should not be scolding #BlackLivesMatter activists on what the “right” way to protest police shootings is. Calling out allies for their blind spots is not “ingratitude” or pointless infighting. Benevolence in intention is not the same as benevolence in effect.

GW: And can there even be benevolence in such a power dynamic, the prisoner and her keeper? We have plenty of evidence to the contrary, some disturbingly recent. E.g. California prisons admit to sterilizing 150 women inmates without consent, is that benevolence? Can there be true consent so long as Lilith is a prisoner? The benevolent overlord in me wants to say no because prisoner and guard are not peers.

“She [Lilith] was terrified that she would be hurt. But she felt she had to risk bargaining, try to gain something, and her only currency was cooperation.”

But then I start to think about how assuming victim status for the imprisoned is another way to deny agency. This strips away another level of a person’s humanity and this is what lies beneath Lilith’s complicity with the Oankali. It is a question that defies easy answers which is the hallmark of good fiction and one that Butler deploys throughout.

TM: I like how Butler starts off with a story that seems, at first, to be heading in a very Gene Roddenberry direction: Ah, if only we could look past our differences, if only we could put aside our fear of and prejudice toward the Other, we’d mutually benefit! Or think of The Day the Earth Stood Still: another sci-fi classic, about more enlightened aliens scolding us into peace. But it’s a much more ambivalent story, the Oankalis’ benevolence more like that of the “good” plantation master.

GW: But she never lets that ambivalence resolve into an easy rejection of either the humans or the Oankali positions. The humans’ suspicion (even when taken to evil extremes) is never really unjustified, but the Oankali are never exposed as actually evil.

TM: A brilliant professor friend compared the Oankalis to “nice” Western colonialists: “oh, we’re just so irresistibly fascinated by you,” they keep telling Lilith, their beautiful-yet-dangerous Other. They just can’t leave us alone! It makes me think of Fenimore Cooper’s questionable romances of lost Native Americans, or modern conversations around cultural appropriation. Interference doesn’t have to be malicious to be destructive.

“You are horror and beauty in rare combination. In a very real way, you’ve captured us, and we can’t escape. But you’re more than only the composition and the workings of your bodies. You are your personalities, your cultures. We’re interested in those too. That’s why we saved as many of you as we could.”

GW: So we have genetic and cultural appropriation happening in one corner while another in another, rebels horrified by the interchange, revert to nativism.

Lilith and the other humans have experienced some body horror already with her genetic manipulation, will the Oankali too? After all Oankali’s are gene traders they give and they get. In Dawn the Oankali’s received in trade the gift of cancer which allows them to regenerate parts of their bodies. Is it possible that some of our more frightening tendencies (like hierarchy and self-destruction) will be expressed by the Oankali?

TM: Come back in November to find out!

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.