Toni Morrison’s haunted slave-narrative Beloved (1987) and Ridley Scott’s space-horror flick Alien (1979) are unlikely bedfellows, but both are modern successors to the Gothic tradition — this is actually pretty obvious upon a moment’s reflection. Beloved is literally a haunted house story, haunted above all by the radical cruelties of slavery; Alien has its unforgettable monster, its resilient heroine, its ruins and sublime terror. And both — this is also obvious, once you think about it — feature monstrous, deadly offspring, following a surprising trinity of hit horror movies from the 60s and 70s that revolve around demonic children: Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), and The Omen (1976).

Theatrical poster for Rosemary's Baby (1968)

This decade, the decade of the watershed Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade (1973), created a troubled but rich aesthetic assembled out of the nightmares of pro-life and pro-choice abortion rhetoric, a new, American Gothic about pregnancy and vulnerability. And Beloved and Alien are two of its finest achievements.

“Gothic Technology” and Gothic Feminism

The original, 18th-century Gothic (think Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho, or M.G. Lewis’s The Monk) and the later, Victorian Gothic (Dracula, “The Fall of the House of Usher”) make up a diverse, shambling genre, but two things these texts seem to relish are their monsters and their heroines.

The Gothic monster, writes Jack Halberstam, is a “technology that produces the perfect figure for negative identity,” a figure molded out of the contemporary social anxieties around race, class, gender, empire, etc. — the Other, in short. [1] For example, Halberstam traces how anti-Semitic images of European Jewry — including “Jewish” physiognomy, greed, economic parasitism, and notions of Jews as a “feminized” race — influenced Bram Stoker’s sharp-nosed, Slavic, avaricious, and sexually ambiguous vampire. The Gothic, Halberstam proposes, “tracks the transformation of struggles within the body politic to local struggles within individual bodies,” most visibly the body of the ultimate Other, the monster.

Betcha didn't notice that Star of David before. Dracula (1931).

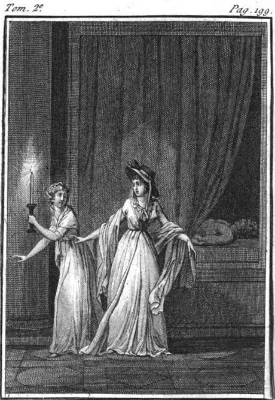

The Gothic genre, especially in its original, Radcliffean form, was also a remarkable opportunity for women writers to accuse the world. It was in Gothic romances that Ann Radcliffe, Clara Reeve, Charlotte Dacre — oh, heck, Jane Austen and Charlotte Brönte, too, Northanger Abbey and Jane Eyre totally count as Gothic — were able to depict the vulnerability and even terror of being a woman in an intensely patriarchal society.

Frontispiece to the French translation of The Mysteries of Udolpho (1798)

It’s the interaction between the Gothic monster and the Gothic heroine that foregrounds what Eugenia Delamotte considers the defining concern of the genre: a preoccupation with boundaries and their violation, “the claustrophobic sense of Otherness, pressing in on the solitary individual who tries, despite it, to keep a distinct selfhood intact.” [2] Hence the Gothic concern with locking enemies out of one’s room, with doors that won’t close and secret entrances; hence also the terror of Dracula’s skin-puncturing fangs.

The Fetus as Monster, Part I

In 1961, a television actress known as 'Miss Sherri' on Phoenix, Arizona’s local “Romper Room,” unknowingly took thirty-six pills containing Thalidomide, which caused grim fetal deformities: “nonexistent arms, twisted legs, flaps of skin for hands and feet, ... a grossly deformed head.” [3] The Sherri Finkbine case became a flashpoint for the early 60s abortion debates, with Finkbine receiving death threats and FBI protection. The Swedish hospital that ultimately performed her termination told her the fetus was too badly deformed to identify as a boy or girl. People talked of monsters. As one avowedly anti-abortion writer stated,

The consideration of monsters therefore can bring us to the conclusion that not everything coming from the womb should be considered a human being. [4]

People talked of parasites. Roe v. Wade captured the abortion debates’ frame as a “contest of rights between women and fetuses,” with the fetus’s “right to life” antagonistic to the woman’s “right to choose” or right of bodily autonomy. [5] The natural image of a being that inhabits a body, survives off its nutrition, is not a (constitutional) ‘person,’ and whose life is hostile to bodily autonomy, is one of parasitism.

Detail from Alien's theatrical poster (1979)

I think it’s time for a disclaimer: I love kids. I’m not advocating a pro-life or pro-choice stance (in this blog post, at least). I’m not saying that all fetuses are parasites (in this blog post, at least — I kid! I kid!), but rather trying to describe how both sides of a deeply felt and public debate put an image in the American imagination of an alien in the belly that feeds off of, and might even kill, its mother.

To state what is now terribly obvious, this is the Xenomorph from Alien, a literal parasite that kills its host through birth. But so is Beloved, the “greedy ghost” of Sethe’s daughter, who “took the best of everything” and starves Sethe into emaciation: “Beloved ate up her life, took it, swelled up with it, grew taller on it.”

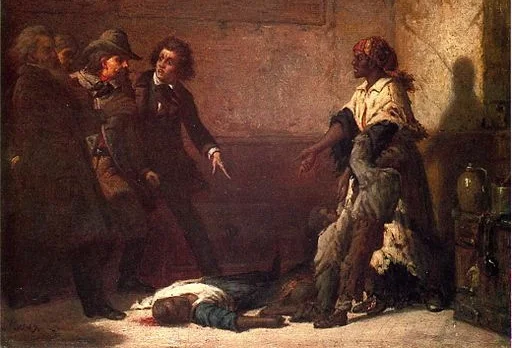

Importantly, Beloved is the ghost of the newborn that Sethe, a runaway slave tracked down by her masters, killed, rather than let her be taken back to the Kentucky plantation. Sethe’s choice — a Gothic one, consistent with public rhetoric of women psychologically traumatized by their decision to abort — is antagonistic to Beloved’s life, and Beloved’s ghost grows symmetrically antagonistic to Sethe’s survival.

Beloved erases the boundaries between her and Sethe, until the three-way monologue that Sethe, Beloved, and Sethe’s living daughter Denver hold in a section without punctuation or distinction between speakers. Sethe’s “distinct selfhood” is violated by a sort of second pregnancy, a oneness with her lost daughter.

Thomas Satterwhite Noble, Margaret Garner, or the Modern Medea (1867). Morrison drew Sethe's story in part from the hotly debated murder case of Garner, a fugitive slave who killed her daughter rather than let her be taken back into slavery.

The Fetus as Monster, Part II

One of the most familiar features of abortion rhetoric is the conspicuous display by some abortion opponents of graphic, gory images of aborted fetuses. I’m not going to post any here, but you know them: mangled, bloody limbs with tiny fingers and toes, to emphasize the fetus’s already-developed humanity. But these grotesques, like the Thalidomide deformities, associate the fetus in the public imagination with horrors. Even if the images do persuade some of the fetus’s personhood, the result is not a ‘person-in-the street’ vision of humanity, but one of violent, violated, Gothic humanity.

With this in mind, consider the gore of the Chestburster scene in Alien — as John Hurt writhes and explodes on the table, he is the very image of violated humanity. Consider the infant alien, spattered red, peeking out of its nest of intestines. Like an aborted fetus, it’s a bloody monster from the womb.

Not that Ridley Scott was necessarily thinking of anti-abortion propaganda when he shot scene; rather, Scott, in summoning up images of what an alien birth might be, drew on a public, cultural nightmare of the anti-birth. Subsequent Alien films — including Prometheus (2012), with its memorable termination scene, have only driven this point further home.

Toni Morrison likewise draws on this cultural nightmare image when she suggests the gore of Beloved’s existence — not just the bloodied infant Sethe kills, but the ghost herself, as she pulls out a tooth:

This is it. Next would be her arm, her hand, a toe. Pieces of her would drop maybe one at a time, maybe all at once . . . It is difficult keeping her head on her neck, her legs attached to her hips when she is by herself. Among the things she could not remember was when she first knew that she could wake up any day and find herself in pieces.

Hijacked Maternity

(Trigger Warning — Sexual Assault)

Rape is a subject always central to the abortion controversy: rape-induced pregnancies were a recurring element in the early illegal abortion exposés, and ‘the rape exception’ was often discussed in the debates of state and federal legislatures. Importantly, rape and the threat of rape is a central element of the Gothic tradition as well, perhaps as defining a trope as ruined castles and secret doors. For an utterly brilliant look at bodily autonomy, Lockean property theory, The Mysteries of Udolpho, and Alien, please read this beauty. [6] For our purposes, we’ll only observe briefly that both Alien and Beloved feature a very specific, very unusual form of sexual violation.

Toni Morrison. Photo by Angela Radulescu (2008)

First, the Facehugger’s assault of Kane, an oral violation that bizarrely mirrors the other hyper-Freudian attack in the film, Ash’s attempt to strangle Ripley by forcing a rolled-up porno magazine down her throat. The Facehugger attack has a strictly sexual function (to incubate the Xenomorph offspring), but no erotic valence: this rape, like many, is about power and control — specifically, reproductive power — not pleasure.

Second, in Beloved, the schoolteacher’s nephews’ violation of Sethe, a forced nursing, in which two teenage boys, after thwarting Sethe’s escape from slavery, hold her down and suckle the milk she’s producing for her newborn daughter. For Sethe, it’s the theft of her milk, more than her beating or any other violation, that torments her. The violation is of her maternity, a hijacking of her reproductive process.

This is the Gothic horror that captures a broader horror articulated by abortion activists: that a woman’s control over her own reproductive system could be taken away from her, and subjected to someone else’s agenda.

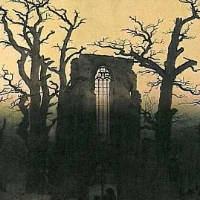

Haunted Houses

The pro-life rhetoric of the fetus as an autonomous human being constructs the womb, by necessity, as a vessel or a home. The Roe v. Wade decision supported such a construction when Justice Stewart asserted the mother’s body is included in the “certain areas or zones of privacy” guaranteed by constitutional law. This right to privacy originated in a line of Supreme Court case decisions interpreting a general right to privacy from the 4th and 5th Amendments, which protected a citizen’s home against encroachment. In the Gothic imagination of the abortion debates, the womb becomes a structure, a house, a ship — and what is a Gothic tale, without its haunted castle?

As Professor Delamotte observes, violence and intrusion in the Gothic occurs in the ruined architecture of castle Udolpho, castle Otranto, Carfax Abbey. [7] The Gothic house is dark, confusing, littered with evidence of specific, previous tenant’s histories. A lightless, obscurely-imaged womb becomes the natural Gothic house for the Gothic fetus. In the anti-abortion film The Silent Scream (1984), which depicts an abortion in the uterus via sonogram, viewers saw a murky, obscure image narrated in sensational terms about pain and violence.

Kane (John Hurt) in the derelict spacecraft.

In Alien, there are two spaceships — the derelict alien craft, and the Nostromo — both with womblike resonances. The derelict’s dark, dripping, round rooms and chamber of Xenomorph eggs, the Nostromo’s computer ‘Mother’ and the birth-like emergence of its crew from their hypersleep pods, all point to this, but these are industrialized or cheerless spaces, estranged from their inhabitants.

In Beloved, Denver regards the 124 house “as a person rather than a structure,” haunted by a “baby ghost.” But the haunted womb image develops even further as Beloved attempts to describe a memory from “the other side,” where she is not just the infant Sethe killed, but also a ghost from the Middle Passage:

“Dark,” said Beloved. “I’m small like this here.” She raised her head off the bed, lay down on her side and curled up.

“Were you cold?”

Beloved curled tighter and shook her head. “Hot. Nothing to breathe down there and no room to move in.”

“You see anybody?”

“Heaps. A lot of people is down there. Some is dead.”

Ridley Scott once said of Alien, “It has absolutely no message. It works on a very visceral level and its only point is terror, and more terror.” [8] But while there’s no hidden message in Alien or Beloved, these radically different works reveal the influence of a highly charged American discourse around abortion. The ultimate concern of this “Childbirth Gothic” is the modern family, and the implications of leaving behind old assumptions and voicing long-silenced narratives. Like any growing pain, its simplest expression is in fear, just as the Gothic has always fashioned monsters out of cultural shifts and awakenings. And since the debate is far from over, we can only suppose artists will continue to mine this rich aesthetic.

Sources

Alien. Dir. Ridley Scott. Perf. Sigourney Weaver, Ian Holm, Tom Skerrit. 20th Century Fox, 1979.

[3, 5] Condit, Celeste Michelle. Decoding Abortion Rhetoric. Chicago: Univ. of Ill. Press, 1990.

[2, 7] Delamotte, Eugenia C. Perils of the Night: A Feminist Study of 19th-Century Gothic. Oxford: Univ. Press, 1990.

[6] Fitzgerald, Lauren. "(In)alienable Rights: Property, Feminism, and the Female Body from Ann Radcliffe to the Alien Films" in Romanticism on the Net: An Electronic Journal Devoted to Romantic Studies, Vol. 21, 2001.

[4] Grisez, Germain G. Abortion: The Myths, the Realities, and the Arguments. New York: Corpus Books, 1970.

[1] Halberstam, Judith. Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters. Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 1995.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. New York: Knopf, 1998.

[8] Thompson, David. The Alien Quartet. New York: Bloomsbury, 1998.

Note: This post is a reduced version of an old academic paper, which cites a lot more sources; the above sources are only the key ones, and do not include the many critical essays on Alien and Beloved that I consulted in developing this thesis. If you want a complete list, (a) feel free to contact me on Twitter @mrbruff, but (b) are you sure?

Carmen Maria Machado’s genre-bending memoir is a formally dazzling and emotionally acute testimony of an abusive queer relationship.