Southern Gothic literature is stepping out from the haunted shadows of pecan trees and peach blossoms (and "regional fiction" shelves) into modern must-read lists. Today, Fiction Unbounders Lisa Mahoney and Amanda Baldeneaux embark upon a three-part exploration of speculative fiction within the Southern Gothic genre, starting with short stories.

Traditional Gothic literature was neither clear-cut ghost story nor horror, but featured grotesque elements that would go on to influence everything from pulp fiction to slasher pics. Gothic lit first came into vogue in the late 18th Century, when rational classicism was admired. But these classic Gothic stories focused on a deep suspicion and fear of what that Enlightenment left behind: the unreformed Catholic Church, a corrupt, despotic aristocracy, and the superstitions and injustices they embodied. To that end, traditional Gothic tales contain combinations of depraved monks and priests; decaying, maze-like castles that trap innocent maidens and hard-working heroes; ghosts or the unsound rattling chains in towers; sick aristocrats as the last of their lines; and the trap of social status symbolized by dank dungeons and crypts. Once the Gothic made its way to America, those same themes reappeared, with startling and incisive transformations.

The Missing Link: “The Fall of the House of Usher” by Edgar Allan Poe

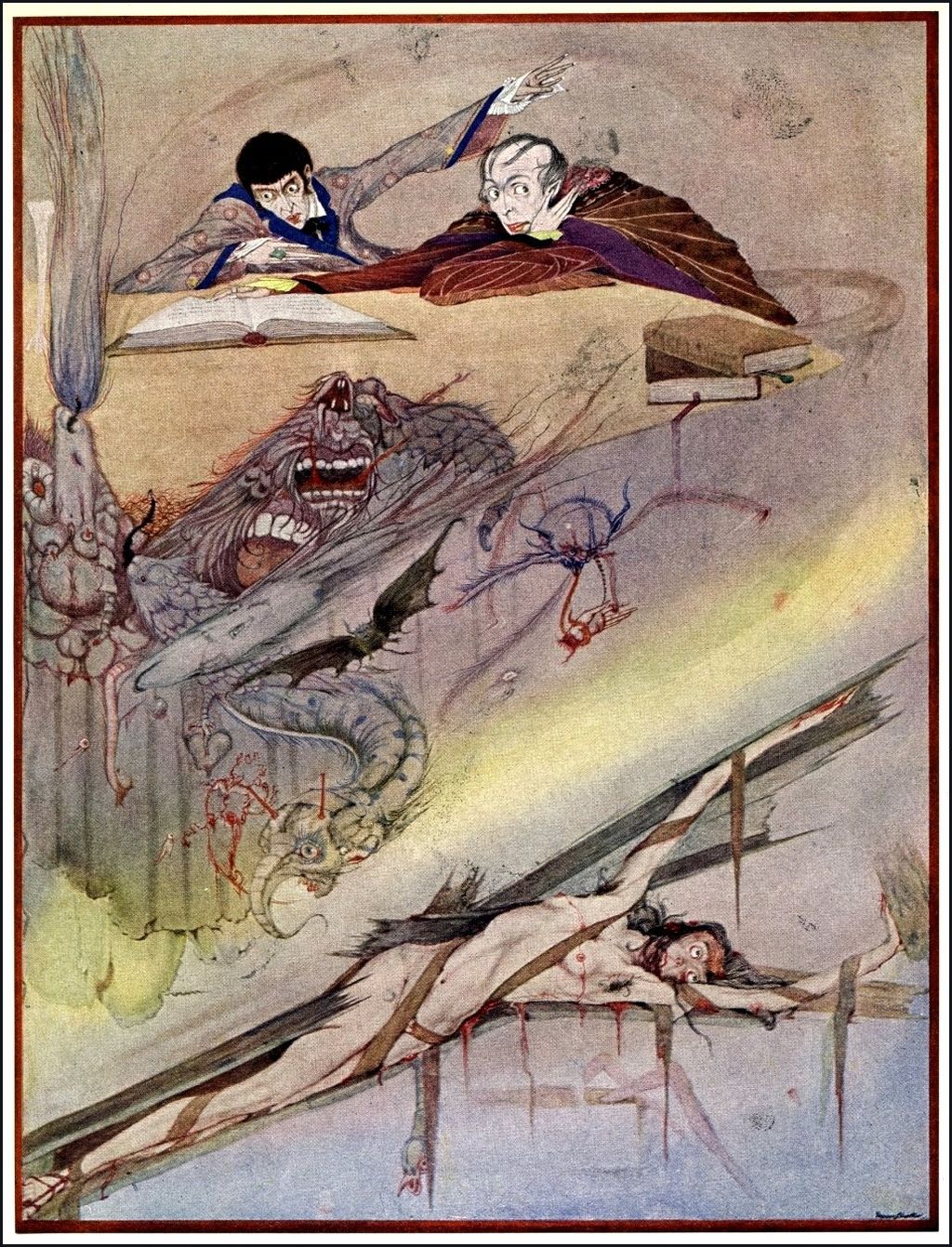

Harry Clarke, "Say, rather, the rending of her coffin," illustration for "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1923)

“The Fall of the House of Usher”, by Edgar Allan Poe, is the short story in which earlier, shocker Gothic novel elements coalesce into an American grotesque Gothic. In Poe’s story, the young hero rides through an oppressive, unnatural swamp encircling a mansion. “I looked...upon the bleak walls, upon the vacant eye-like windows, upon a few rank sedges, and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees--with an utter depression of soul….” He has come at the request of his old friend Usher, who is isolated, unaccountably fearful, and sick. Usher, still a bachelor, is losing (or has already lost?) his mind, and lives with a sickly maiden sister, who moves like a ghost through the halls. They’re the last of their line, and their insanity is the price of refusing to marry and procreate with outsiders. The aristocratic line of Usher has, in essence, cannibalized itself in the name of genetic purity. In the end, the house literally falls, and the swamp closes over the bodies and the ruin of the house’s former grandeur, ending the House of Usher and its blighted lords and ladies forever. "The Fall of the House of Usher" applies the classic Gothic tropes of decadent aristocracy and ghoulish goings-on to Poe's America in a straightforward, recognizable form; but already there are hints of how the genre would evolve in the Reconstruction South.

The Southern Twist

While Gothic literature warns of abusive religions and aristocracy prevalent in medieval Europe, the post-Civil War South is another place once wealthy because of past abuses. Slave owners, enriched by the labor of the oppressed, are the South’s incarnation of depraved aristocrats with absolute power. Their mansions and plantations cannot be maintained without slaves, and their inevitable decline into decay and ruin is a delayed reflection of the corrupt souls of those who profited by exploiting others. In Southern Gothic stories, depraved pastors or preachers hark back to the priests and monks of Gothic stories, and impenetrable forests and decrepit mansions stand in for the maze-like, crumbling castles of Europe.

Although mythic elements, crime, and class tension abound in Southern Gothic (as in “Barn Burning” by William Faulkner), racial tension is arguably the genre’s defining characteristic. Slavery’s legacy haunts Southern Gothic and contrasts starkly with the biblically driven culture’s belief in the divine and equitable love of Jesus. Southern Gothic writers expose the cognitive dissonance and contradictions of a mindset that tries to square racism, historical pride, and a belief in an all-loving Christ who wouldn’t condone slavery, with aristocratic classes and racism. Southern Gothic writers pull no punches regarding the difficult truths of the region’s past (and sometimes, present).

Flying South: “A Rose for Emily” by William Faulkner

Arguably the defining Southern Gothic tale, “A Rose for Emily” is William Faulkner’s take on Poe’s themes in “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Emily, an aristocratic maiden of an old Southern family, financially ruined by the loss of unpaid labor following the Civil War, is forbidden to marry anyone not meeting her haughty father’s standards. What’s a girl to do then, besides poison the first carpetbagger to cross her path and keep his corpse as her bedmate? Well, that sounds reasonable. Although superficially a horror shocker of murder and necrophilia (replete with crumbling mansions, an aging lady who is the last of her line, and repressive sex rules), “A Rose for Emily” is a scathing critique of a South that refused to let die the horrifying ideals of a perceived “glorious” past built on a foundation of exploitation. Clinging to a dead past is no different than clinging to a dead, uh… we prefer not to revisit the story’s visuals again.

When the Past Lingers Instead of Dying: “Clytie” by Eudora Welty

Narcissus loves his image in water, but Clytie is repulsed by the truth she sees reflected there. Caravaggio's "Narcissus" (c. 1594).

But enough about the men; Southern Gothic literature rose to prominence under the pens of southern women writers (fight me). Like the stories “Usher” and “Emily,” “Clytie,” by Eurodra Welty, depicts a once-wealthy family clinging to their former status but fallen into decay and madness. Farr’s Gin, the story’s setting, is named for Clytie Farr’s family, implying that the family once made bank on a cotton gin likely powered by exploited labor, which went bust once they had to pay wages. Clytie’s mad older sister, Octavia, won’t let anyone enter the Farr house, not even their dying father’s old nurse, whom the father begs to see. She won’t allow anyone to witness the family’s decrepitude, even if it means being a monster to the family she’s trying to “protect.” One Farr brother shot himself, another held a gun to his fiancee’s breast when she threatened to leave him. Now, dashing catch that he is, the brother is a shut-in bemoaning how the world has turned against him with zero self-reflection on the heinousnous of his actions. Sister Clytie just does what she’s told.

When Clytie develops a sexual attraction to the barber (the only outsider let inside, to maintain the father’s respectability on his deathbed), she can’t handle it. Her inability to identify or act on romantic and sexual feelings manifest in her complete breakdown after one physical touch. Outside, Clytie gazes at an unrecognizable reflection in a barrel of water. When the face morphs into her own, she sees that she’s let herself be completely dominated by Octavia’s perversion of reality, and she plunges in and drowns herself. Like the grey hair next to the carpetbagger’s corpse in “A Rose for Emily,” we’re left with the startling image of Clytie’s stiffened stocking feet split unladylike in the air.

Of course, it wouldn’t be Southern Gothic if the story was just about sexual repression and being too snooty for one’s own good. The Farr’s Gin townspeople ask, why won’t the senior Farr just die? The father is the barely-surviving embodiment of southern culture that was “destroyed” by the Civil War, the culture that built wealth with slave labor and mistaken righteousness. Now it’s all decaying, but it lingers on, poisoning the house, as embodied by Farr’s sickly body, Octavia’s madness, and the siblings’ deluded self-importance.

A Gothic Heroine's Journey: “A Worn Path” by Eudora Welty

“A Worn Path,” another story by Eudora Welty, is a mini-heroic journey through a Southern Gothic landscape. Our brave and determined heroine, Phoenix—an intentional nod to the bird that resurrects itself from ash—is a black grandmother on a quest. On this quest, Phoenix must walk all day with her cane, overcoming trials that range from heat and fatigue, to thorn bushes that threaten to tear her dress, to racism. Phoenix warns the wild hogs and feral creatures not to bother her as she journeys down the dirt path through the woods, but like Little Red Riding Hood, the wolves are always near. A fiendish white hunter with a gun helps her out of a ditch and then, seemingly innocuously, jokes with her. Ominously, a dead bobwhite bird hangs from his belt. Then, out of nowhere, he points his rifle at her; showing his true, wolfish colors.

She stood straight and faced him.

'Doesn’t the gun scare you?' he said, still pointing it.

'No, sir, I seen plenty go off closer by, in my day, and for less than what I done,' she said, holding utterly still.

He laughs, lowers the gun, and lets Phoenix go, advising her to stay home where nothing will happen to her. This is the goal of those who have been in power over others and that power has been challenged: maintain that power at all costs, including through threats and violence. A black woman on a quest - free and strong - is a threat to the status quo of white supremacy, and warning Phoenix to stay home is a warning to all African Americans to stay out of the white man's way and out of sight. Phoenix isn't having it. Like her namesake, she rises again, because she must reach the mythic Otherworld, a doctor's office in a town dressed to the nines for the coming Christmas holiday, to save someone she loves. There, she acquires the mythic Elixir, in this case, medicine that her sick grandson needs. A nurse informs the reader that Phoenix's grandson drank lye some time ago, and will need the medicine regularly for life to live. Lye is poison, and it seems inevitable that the boy is doomed, much like another child celebrated at Christmas who also rose from the ash of death to be reborn. "Phoenix" becomes more than the grandmother's name, here, reminding us that the strong will always rise from the destruction of oppression and exploitation, and that though the boy may be weakened from past poisoning, he will be ministered to and saved over and over, until all of the past abuses are finally expunged from the body. In this way, Phoenix's quest, journeyed again and again to save the boy, isn't Sisyphean, but Herculean, and in her rising, the world will be forever changed for the better.

Puberty & Death: "The Grave," by Katherine Anne Porter

"Dancing Moon Rabbit" by Choestoe on DeviantArt

Not all Southern Gothic stories deal directly with death. “The Grave” by Katherine Anne Porter is heavy with foreshadowing of death's inevitability, but the only actual death in the story is that of childhood. Paul and Miranda are a young brother and sister whose family was once wealthy (sound familiar?), but have since had to sell off land to make ends meet, including land once occupied by the family graveyard. The ancestral bodies are dug up and relocated, but leave empty craters in the ground. Paul and Miranda trespass onto the land that was once theirs, hopping into the empty holes and finding treasures that include a dove-shaped coffin pin and a gold ring. They're out shooting small game, and Miranda resents her brother's insistence that she let him shoot first and defer to his "expert" marksmanship. While admiring the gold ring on her "grubby" thumb, she considers how her attire of boys' overalls and sandals are considered uncouth by the townspeople, and begins to wonder if she should begin wearing her dresses and letting her brother make (and call) all the shots.

While contemplating, Paul fires his rifle, shooting a rabbit through the head. This is uneventful in itself, until Paul begins skinning the rabbit and the children discover the rabbit was pregnant, with well-formed babies just days from birth. The children realize they've done something, ahem, gravely wrong, and bury the rabbit with her babies tucked back in her belly. The image of the baby bunnies torn from their mother is grotesque in itself, and the crux of a story about maturation and the end of innocence. Further, rabbits are a symbol of abundance and fertility, two things—wealth and immortality—seen lost throughout Gothic stories. The story ends with Miranda grown, independent in a foreign land, reflecting upon her brother’s face in that far-away day’s sunshine, a face she can barely remember, in a time and age that even remembering is now a trespass upon.

Escaping the Past: “Medusa” by Tania James

Medusa lost her beautiful head rather than sacrifice her power. Caravaggio's "Medusa" (c. 1598)

Old-time religion goes way back in Tania James’ story “Medusa,” published in the centennial issue of Oxford American. Hunted by an assassin, Medusa and her 37 scalp-fused snakes find peace in a quiet “Southern hamlet,” where Medusa hopes to live an uneventful life, but mostly hopes just to live. In the story, Medusa is a stand-in for African American and minority women who have faced centuries of stereotyping as angry and volatile, who have been ostracized as different for their appearance and hair, and who have been persecuted simply for existing as not-white in America. Despite attempts to insulate herself against the fear and hate of those around her, Medusa falls for a “delivery guy” whom she feels safe enough with to reveal her head of snakes. Despite pretending to be fine with her, the man clandestinely and cruelly works to sever Medusa from who she is and what she loves and make her ‘acceptable’ to him and society. Medusa can’t regain what he took, but she can regain her power. The story, though not overtly Gothic, deftly handles themes of racism and persecution through the framework of mythic retelling.

* * *

What are your favorite Southern Gothic short stories? Tell us in the comments below, and return with us at the end of April to continue exploring the ghosts of past depravities, commingled with the wild beauty of southern backwoods and small towns, as we tackle our next round of Southern Gothic reads: novels. Want more great writing on the south while you wait? Peruse fine southern writings over at The Bitter Southerner, Scalawag, and Oxford American, bourbon optional.

In the crucible of catastrophe, we learn deeper truths about love, loyalty, and compassion.