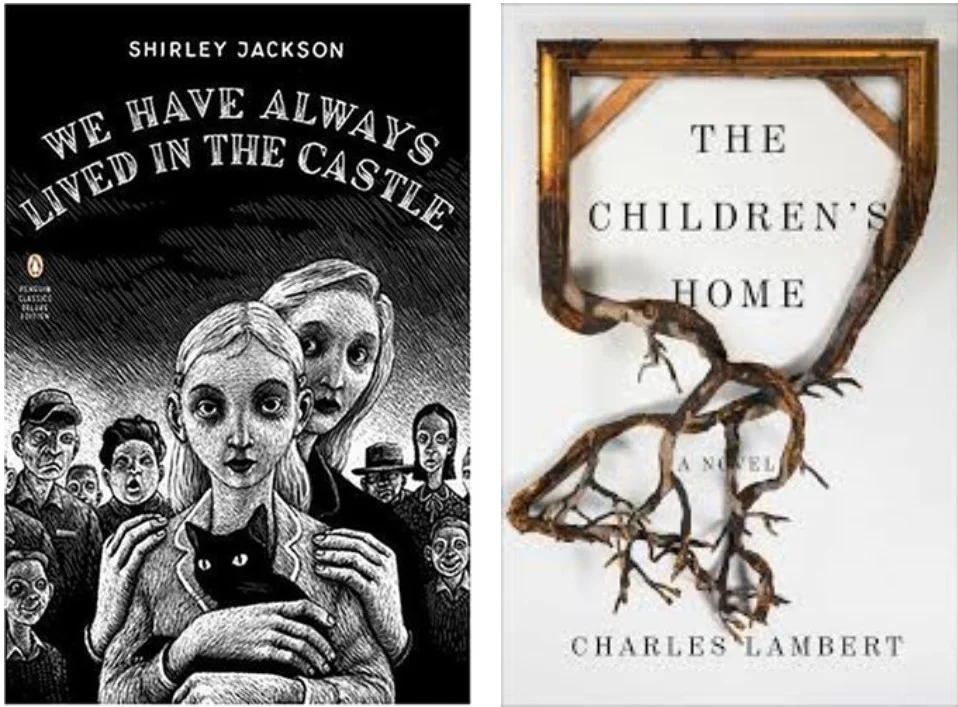

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson, and The Children's Home by Charles Lambert

The Shirley Jackson Awards announced their 2015 nominees last week, recognizing stand-out literature in the realms of psychological suspense, horror, and dark fantasy. These three elements are easy to spot in Jackson’s own works, but when a light is turned on, deeper, sometimes subtler, elements come crawling out from beneath the shadows: madness, sexual repression, class criticism, unspoken atrocities, contrasts between a Christian patriarchy and the lost goddesses of older religions. A feminist presence also appears, notably in her American Gothic tale of two outcast sisters in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, published in 1962.

A Tale of Two Loners

Authors honored by association with Shirley Jackson also thrive in the dark corners of fiction, corners where the stairs creak when no one is there and throttled rose bushes thrive on acid fertilizers. Charles Lambert’s latest novel, The Children’s Home, reaches across time to sit beside Jackson’s We Have Always, sharing space on a cobwebbed bench. Both novels speak quietly, their inhabitants shrouded in suspected murder, psychological witch hunts, and the empty spaces abandoned by the world’s exorcised mother goddesses. In We Have Always and Children’s Home, these goddesses are symbolized by Hestia, goddess of the hearth and home, and Artemis, the huntress.

Be Wary of the Blackwood Sugar Bowl

Jackson’s novella places the outcast goddesses firmly at the center of the story; Merricat Blackwood, an embittered 18-year-old, embodies Artemis, archer goddess of the hunt and the moon. “The people of the village have always hated us,” Merricat says, though the villager’s vitriol has grown more sour in recent years. Merricat is ostracized as the endcap member of a family of snobs. Murdered snobs, save for Merricat and her older sister, Constance Blackwood. Constance, while patient and kind toward her sister, is feared and ridiculed by the townspeople, despite her acquittal of murder charges leveraged against her for the family’s deaths. Children sing to Merricat as she walks down the street, “Merricat, said Connie, would you like a cup of tea? Oh, no, said Merricat, you’ll poison me. Merricat, said Connie, would you like to go to sleep? Down in the boneyard ten feet deep!”

Merricat is protective of the fragile Constance, burying cherished items around the family property as talismans to keep bad luck and strangers away. She reassures Constance that “on the moon,” where all things are inverted, things will be better; “On the moon Uncle Julian would be well and the sun would shine every day. You would wear our mother’s pearls and sing, and the sun would shine all the time.” Constance prefers the kitchen to space travel, though, caring for Merricat through cooking and cloistering herself away from the judgmental eyes of the townspeople. A spinster in her 20’s, Constance solidifies her place as the keeper of the hearth and vestal virgin of the goddess Hestia.

Don't Bring a Knife to an Acid Party

In Lambert’s novel, only battered traces of the goddesses remain in the post-war world of Morgan Fletcher, a disfigured shut-in whose broken family brings to mind the crumbling remains of the cult of Artemis, from the arrow embellishments on the iron fence surrounding the property, to the collection of cultural artifacts “hunted” across the world by his grandfather. Morgan has his own Hestia in his housekeeper, Engel, who keeps “the running of the place arranged behind his back” to save him having to face the servants after his “accident,” a meeting of his face with a jar full of acid thrown by his mother. Morgan prefers his books to people, kept in a room with no windows and no day or night, no light or dark. In the Fletcher home, the book room, the heart of worldly knowledge, is neither good nor evil; knowledge’s power is neutral in itself, but can be callous or kind depending on how it is utilized.

In addition to living with the shame of a face that frightens the villagers, Morgan keeps close tabs on his sanity, always fearing he will be lost to the madness that consumed his mother. His timorous grip on reality is shaken when strange children begin appearing in his house, seeming to appear out of thin air and disappearing again at will. “Our mothers are dead,” they tell him, and in their orphanhood Morgan finds kinship and an inverted sense of family as they begin to care for him.

Amanita Phalloides, the Death-Cup Mushroom

The death-cup mushroom for your reference. Don't eat this.

Both the Blackwood sisters and the inhabitants of the Fletcher estate are orphaned by violence; the Blackwoods by murder, Morgan by his mother’s suicide, and the eerie children by circumstances they will not name. Each family also resides close to an enclosed garden, approximations of Eden where Morgan, Merricat, and Constance find a sacred refuge from the outside world. Where Eden was a paradise designed and sown without a mother, causing its first inhabitants to suffer beneath the iron will of a father’s unchecked power, so the gardens of Jackson and Lambert are motherless and laced with the dangers of poison mushrooms and thorn bushes. The world in both novels is harsh and unforgiving.

In the Blackwood home, before the deaths, Mr. Blackwood ruled his family with absolute authority, sending Merricat to bed without food for childish antics, and casting Constance as the house servant because she was too kind to protest. In the wake of the murders, the townspeople, who always resented the Blackwoods for their wealth, grow even more prickly toward the orphaned sisters. The countryside outside of the Fletcher estate is in ruins, the remnants of a war leaving villages in poverty and martial law in effect. The only nurturing voices to be found are in Constance and Engel.

Cronos Consumes His Children

Morgan attempts to provide shelter and comfort for the children, but grows increasingly frightened of them after stumbling across a group gathered around an anatomical torso of a pregnant woman, seemingly worshiping it through chants of “ma-ma-ma-ma. The primal sound.” The pregnant figure, stored for decades in an attic trunk, is the mother figure restrained and hidden away, unable to free herself with her arms and legs removed. The children’s worship recalls Artemis, the virgin goddess of childbirth; a primal mother figure, lost in the patriarchal post-war world where Morgan resides. Even their chant, “ma,” echoes Sanskrit origins for the words “moon” and “mother,” further recalling the lost matrilineal moon cult of Artemis.

Locked in a prison of their own making, the Blackwood sisters are also stunted and restrained, both in physical proximity to the world and emotional development. Merricat is child-like in her perceptions and limited in scope to a small collection of library books she won’t disturb from their ordered placement. She toes visible madness in her insistence that hedge-witch style rituals will keep the Blackwood home in an order she prefers, occupied by only the people she prefers. When an interloper, cousin Charles, appears - interested in Constance, their father’s gold watch, and the family safe - Merricat attempts to exorcise him by dirtying the room where he stays, their father’s room. “He would be lost in a room of leaves and broken sticks,” Merricat rationalizes, believing the man trying to assume her father’s role would leave if she made the room “unrecognizable.” She flings mud and unmakes the bed, creating a wild state without the forced rules and expectations imposed by Charles, her father, and the villagers.

I am Only a Child but Already I Have Understood the Wickedness of the World

The children visiting Morgan have similar goals: to dismantle the Fletcher family factory run by Morgan’s sister, Rebecca. Rebecca has turned to madness like their mother, but rather than self-destructing, has embraced the use of cruelty and force taught by the war to bend the world to her will. In her factory full of children, she is an inverted mother, growing children but harming them rather than nurturing them. To restore feminine balance to an overly masculine world, she must be killed so that Morgan, the compassionate sibling embodying the traditionally feminine characteristics, can regain control of the family fortune and lands.

Destruction is also necessary in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, where Merricat, acting as Artemis, burns the house. In the ruins of the fire, only the roofless kitchen remains, a symbolic creation of a traditional Greek oikos, a home where the fire of Hestia is rooted in the ground and the smoke allowed to rise skyward toward Heaven. After the fire, all that is left is Constance’s kitchen, her hearth, with the roof destroyed and the oven’s fire pillaring up to the sky. As the villagers reflect and feel remorse for their treatment of the Blackwood girls, gifts of food appear on the home’s charred doorstep: offerings to the goddesses have been reinstated, and balance via feminine reverence restored to Merricat’s world.

There is far more to unpack from Jackson and Lambert’s novels, including the mysteries of who poisoned the Blackwood family, and the origins of the ghostly Fletcher children. Perhaps if we as readers can stomach the dark secrets of fictional families, we can open our eyes wide enough to acknowledge the unspoken atrocities committed by our cultural family, and hold out a welcoming hand to the banished members of our collective kin, matrilineal and other, just as Jackson and Lambert nudge us to do.

You won’t want to miss this haunting debut collection. Thin Places by Kay Chronister available now from Undertow Publications.