I had a dream, which was not all a dream. — Darkness, Lord Byron

The Strange Library, a novella by Haruki Murakami with illustrations by Chip Kidd, is an odd, beautiful little book. It tells the story of a lonely, unnamed boy who finds himself imprisoned in a labyrinth beneath a library. The boy’s captor is an old librarian who wants to eat his brains—but only after the boy has memorized the contents of three obscure and weighty tomes on the subject of tax collection in the Ottoman Empire. Two other characters are trapped in the labyrinth with the boy: one is a man dressed in a sheepskin, who makes the best fried doughnuts the boy has ever tasted, and the other is a mysterious, beautiful girl, who can’t speak and who may or may not exist, but who does her best to help the boy make sense of his predicament.

If this strikes you as the stuff of dreams—or nightmares—then you’re on the right track. As in a dream, the passage of time becomes uncertain and the action unfolds in a sequence of increasingly disturbing images and events that shouldn’t hold together but somehow do. We suspect it isn’t real, it can’t be, and the boy himself confirms our suspicions at the end, long after he has escaped from the library basement. He hasn’t told anyone what happened, and he has done his best to to put the ordeal behind him, though he admits that he sometimes still thinks of it:

“That leads me to memories of the sheep man and the beautiful voiceless girl. Did they really exist? How much of what I remember really happened? To be honest, I can’t be certain. ”

For a moment we feel reassured, secure in the knowledge that we were right to distrust the strange tale. The boy was never in danger; there is no labyrinth hidden beneath the library, no scowling librarian waiting to saw off the top of the boy’s head and slurp up his brains. The world could never be so cruel or grotesque.

Then, on the last page, a shattering revelation changes everything. What at first appears to be haphazard is anything but. The boy’s dream is not as difficult to bear as the reality it masks.

Haruki Murakami giving a lecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2005. Photo: wakarimasita. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Murakami renders this heartbreaking story in a simple, unadorned style that makes even the most surreal moments feel understated. The spare prose, translated by Ted Goossen, stands in stark contrast to the book’s physical form, which announces its strangeness in bright colors and bold strokes. Designed and illustrated by Chip Kidd, it is a slim volume, just 96 pages. On a bookstore shelf, sandwiched between the author’s more substantial works, it is easy to overlook. But once it catches your eye, you can’t look away. A pair of oversized cartoon eyes dominate the front cover. They evade your questioning gaze and at first distract from the black-and-white image of a snarling mouth—feline? canine?—over which the author’s name has been superimposed in heavy yellow type. Is this a warning or an invitation ... or both?

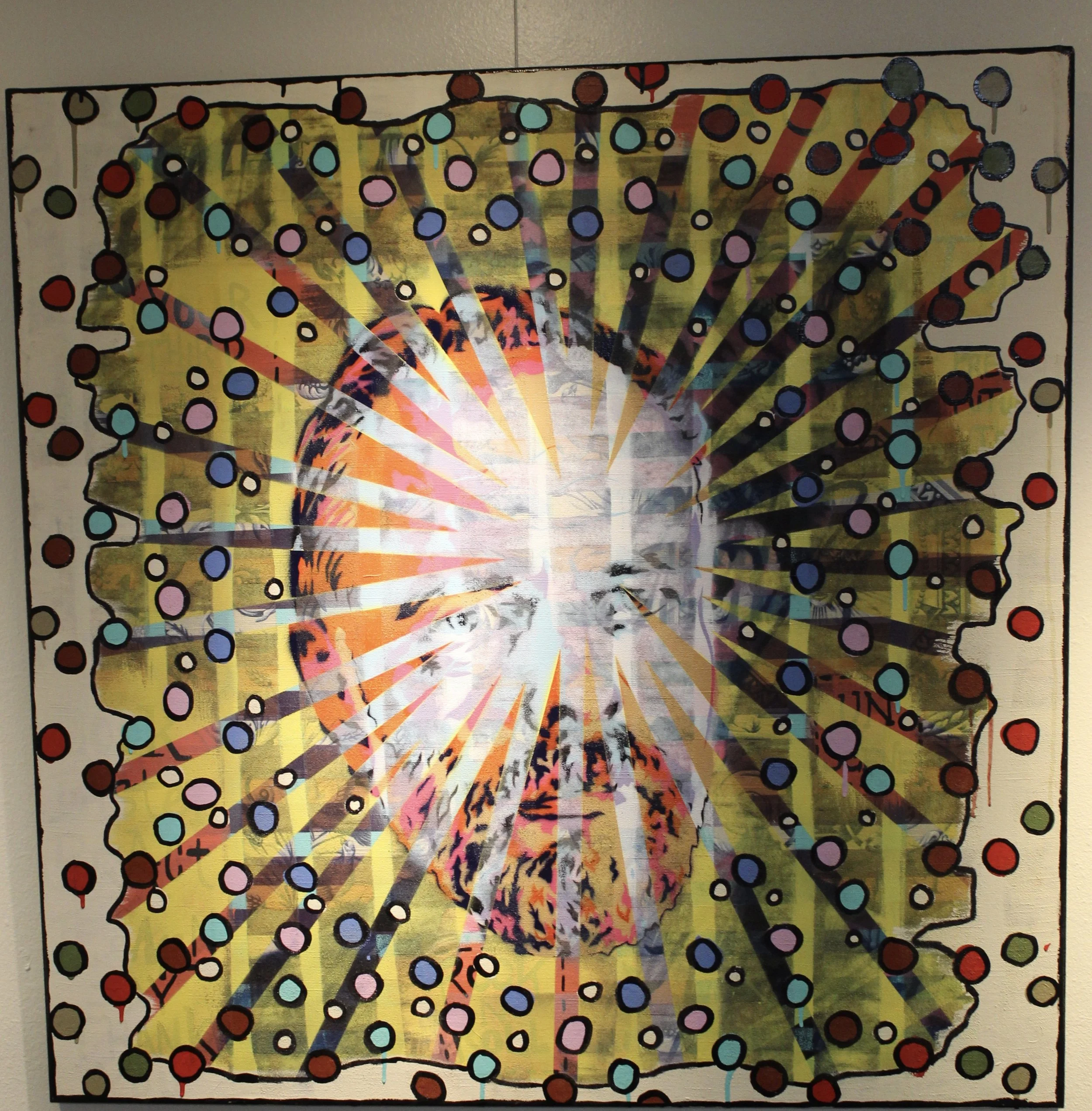

From cover to cover, Kidd’s illustrations, which comprise almost half the book, threaten to overwhelm Murakami’s text. The images respond to events in the story, but they aren’t literal depictions of scenes. Kidd takes an impressionistic approach, echoing the brooding atmosphere of the boy’s imprisonment and escape from the labyrinth. The illustrations overlap and compound, sometimes grainy, often magnified, always too close for comfort—insect-patterned paper and an origami bird, a leering moon and a sugary doughnut, obscured faces and staring eyes. The effect is disorienting, hypnotic and—dare I say?—dreamlike. You don’t read this book so much as you feel it.

What does it all mean? The question lingers after a first encounter with The Strange Library. I won’t presume to answer it for you, except to say that the book rewards multiple readings, and it isn’t as opaque as it seems the first time through. Symbols abound, as in any dream, urging you to look closer and delve deeper in search of the story’s hidden meaning. I believe I’ve found the threads that lead to the center of the labyrinth and back out—but, like the boy, I can’t be certain. Perhaps dreams aren’t really so different from reality after all.

“My mind was in turmoil. It was too weird—how could our city library have such an enormous labyrinth in its basement?” Etching: Toni Pecoraro. CC BY 3.0.

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.