Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow, which recently celebrated its 20th year anniversary, features a Jesuit expedition to Rakhat, a newly discovered planet around Alpha Centauri, inhabited by the proud Jana’ata and the pacific Runa. The expedition’s driving force, the charismatic Father Emilio Sandoz, embraces the mission as God’s Providence, only to see it fall into disaster and brutal personal degradation when the missionaries fail to understand the shocking relationship between the Jana’ata and Runa. Unbound writers CS Peterson and Theodore McCombs discuss The Sparrow alongside Michel Faber’s space-missionary novel, The Book of Strange New Things (2014) and Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s classic apocalyptic triptych, A Canticle for Liebowitz (1960).

Theodore McCombs: In The Sparrow, The Book of Strange New Things, and even at the end of A Canticle for Liebowitz, we have Christian clergy—Jesuit priests, a Protestant pastor, and Catholic monks—launching into space. It’s a funny image, since we tend to associate space travel stories with scientists, military, and adventurers; and while clergy have also been all these things, these men seem preoccupied with a salvation history that happens on, and is bound to, Earth. What is it that space offers them?

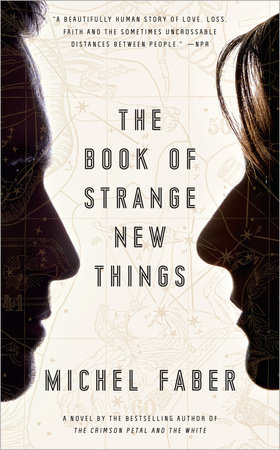

CS Peterson: That history may have begun on Earth, but so many interpretations and practices have turned their eyes to the stars. The Christ claims all authority in heaven and Earth and sends his followers out to make disciples of all nations. Since then, every time the limits of human geography have expanded, so has the definition of “all nations.” Missionaries are among the first ones on the ships into the unknown, emboldened by their sure knowledge that Providence is leading them. It is no wonder that we imagine missionaries going off into the great unknown of interstellar space. All of our sci-fi missionary tales take their cues from history. In The Book of Strange New Things, Peter, the pastor, has been hired by a corporation to evangelize the Oasans, the indigenous inhabitants of the planet Oasis. The motivations of the corporation remain vague and detached from Peter’s missionary work, until it is clear that the Earth is becoming uninhabitable. Those seeking gold and those seeking souls always danced together.

TM: And in Liebowitz, the priests escape the earth to preserve what they can of civilization, knowledge, and religion, as mankind descends once again into a morass of violence. Like monks with illuminated copies of Aristotle high-tailing it for Ireland as Rome burned behind them, they function as storehouses for the dark ages.

CP: My current favorite space missionaries are the Mormons in The Expanse. They are building an intergenerational space ship called the Nauvoo, headed to Tau Ceti. It will travel for hundreds of years on its way to colonize planets around another star. In The Sparrow, through, it is only the Catholic Church that gives enthusiastic support to the Jesuit’s mission to make first contact, without waiting for UN approval. Who are men to stand in the way of a divine mandate?

TM: At heart, Father Sandoz goes into space because wants to know God: space is the great, sublime unknown, a secular stand-in for the divine. And the expedition confronts him squarely with the problem of evil: why does God let bad things happen to good people who are doing just what he wants them to do? How can God be omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent, and yet this well-intentioned Jesuit mission goes terribly, terribly wrong? Sandoz needs a theodicy for the space age, a theological theory of God’s approach to evil that spans two planets and three sentient species.

CP: Marc Robichaux, the young priest in The Sparrow, likes to say, Deus vult: God wills it. That’s one approach, but an awfully fatalistic one. That, if evil happens, it will eventually work out to a greater good. Just look at the crucifixion. Then there’s the option to take every beneficial event as an act of Providence. Anne Edwards, the doctor on the team, retorts, “God gets the credit for everything good; everything bad is the doctor’s fault.” Evil is man’s fault. This same instinct to attribute good things to Providence features in the first part of Liebowitz, when a mysterious wanderer leads young Brother Francis to a trove of ancient artifacts. Back at the monastery, a kind of hagiographical hysteria ensues: In the story, retold and embellished, every event and choice of Brother Francis becomes a moment divinely ordained and laden with clear purpose. But that clarity starts fraught and only gets fraughter the further we get into the story.

TM: There’s a way that setting the problem of evil in space (INNN SPAAAAAACE) exacerbates this anxiety at the heart of Christian theology. Space is so cold, so silent, so merciless, and so empty, it seems to embody all the things a believer secretly fears God to be.

CP: In Liebowitz and Book of Strange New Things, evil is purely humanity’s fault. We bring on the apocalypse through selfishness, and destroy the planet. In one book it is nuclear weapons, in the other global warming. Our passion for knowledge is both what civilizes us and destroys us in Liebowitz.

TM: Do you see that perspective playing out in The Sparrow? That’s St. Augustine’s classic theodicy: God gave us free will and everything from then on is our doing. Russell says in an afterword she wrote The Sparrow in part because she thought we moderns judge the Jesuit missionaries of the 17th and 18th centuries too harshly, that even with our sophistication and more enlightened approach to cultural exchange, we’d screw up first contact because we are just not prepared to encounter that degree of difference.

CP: Perhaps the evil in The Sparrow is the tragically naïve arrogance of the explorer? Every step on their journey is paved with good intentions. We think we know how the universe works, what intelligence, civilization, and beauty are. But we are catastrophically blind to our own assumptions. In 2004, the Discovery Channel aired Alien Planet, a “docufiction” on what it might be like to look for life on other planets. In passing, the narrator states that intelligent life would necessarily evolve from predators, since intelligence is needed for the hunt. Russell skewers that idea in The Sparrow. Yet this cultural assumption is so deeply ingrained that it colors our thinking on everything from political campaigns to myths about famine.

TM: Naïve arrogance is at the center of the misunderstanding that damns the Jesuit expedition.

CP: And in Strange New Things. The pastor, Peter, just totally misses the biological difference that causes the Oasans to die of minor injuries, and take belief in the promise of an immediate resurrection literally. In the tragic climax he realizes what a perverse and catastrophic deception he has caused. But by that point the faith of the Oasans has feet of it’s own. Peter can’t control it.

TM: In Liebowitz too, arrogance is humanity’s original sin, but in that case it belongs to the secular leaders. Except, there’s that long, ambivalent sequence in part III, where the abbot tries to talk a mother out of euthanizing her infant, who’s dying horribly of radiation poisoning. That strikes me as arrogant, but maybe Miller and I have different politics. Miller presents both sides strongly, but he seems to tip toward the abbot saying, I have this metaphysical knowledge that you don’t that puts me in charge of your decision.

CP: Again it's the arrogance of assuming you know God’s mind. In every event, the unseen hand. Things line up, things fall apart. Tragedy strikes and the missionary questions if they heard rightly. A moment of “eli, eli, lama sabachthani.” Finally, the resolution? “His ways are deeper than our ways, there must have been a reason in the greater plan, the church is watered by the blood of the martyrs, etc.” are the pat answers and they suck for the most part.

TM: The Whirlwind barely gives Job that much of an answer. I suppose if anyone had a better one, we could all stop writing books.

CP: But, there is value in that moment. It is when the story of faith becomes interesting. The missionaries, having lost their facile faith and been given the gift of devastating self-knowledge, stand at a crossroads. They can submit to despair or choose to construct meaning in the face of hopelessness.

At the risk of going from the sublime to the ridiculous, I submit that the story in the movie Galaxy Quest follows the pattern of a missionary's journey. The alien Thermians, like the Oasans, take everything literally and think a television sci-fi show is a historical reality, which they try to emulate. The actors are seduced into buying their own con until shit gets real and the human actor Nesmith has to explain to the Thermian captain that they have lied.

Redemption comes when the faith of the Thermians move the actors from cynicism to action. The jaded British actor who rolls his eyes at the trite lines of his television persona transforms into the mythic hero his dying Thermian fan believes him to be. "By Grabthar's hammer" the faith of the Thermian becomes the actor's truth. The story, the idea, has a life and a power of its own, beyond the limitations of the one who tells it.

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.