This is a review of Muse of Nightmares, book two in a duology by Laini Taylor. It contains spoilers for Strange the Dreamer, book one in the series. In the duology’s first book, Taylor introduces a world with no easy answers. The setting is a city called Weep. There, humans live on the land, and blue-skinned gods live in the sky. In the past, the gods took humans against their will and forced them to bear their children. Then these gods stole away both the children and the memory that they had ever been. One day the humans rose up and slaughtered the gods. One human in particular, Eril-Fain, the god-slayer, led the revolt. He also raided the nursery on that day. Fearing that the infants, blue-skinned godspawn, would grow to be as cruel as their powerful parents, the humans murdered them all. Eril-Fain is plagued with guilt over this, which is good; killing infants in the cradle should give a character moral pause. But he is especially haunted, having killed his own infant daughter, Saria.

Unknown to the humans, five godspawn survived. They are hidden children, who live cut off from the world, trapped in their strange, blue-metal citadel in the sky above Weep. The castle is in the form of a seraph. At the death of the gods, it spread its wings to cover the city of Weep in perpetual, oppressive shadow. Eril-Fain, at the start of the book, recruits Lazlo Strange, a dreamer and a librarian, along with some others, to see if they can remove the seraph from the sky.

Strange the Dreamer is a beautiful book, written with heart-melting lyricism. Taylor weaves worlds made of poetry, pathos, and the astonishing discoveries of two young people experiencing a first love. Lazlo is a Romeo with a steadfast heart and dreams worth pulling into the waking world. Saria, who, unbeknownst to her father, survived, is the blue-skinned Juliet. Her gift is to bring nightmares to the residents of weep, a nightly torment for what they did to the gods. Strange the Dreamer is definitely worth reading first, and you might enjoy the two other reviews of Strange the Dreamer on Fiction Unbound, here, and here.

Editor’s Note: From here on out, it’s spoilers for book one. You’ve been warned!

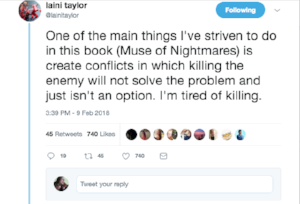

Taylor has set herself a challenge in this series, and in Muse of Nightmares in particular. She set out to write a YA fantasy duology in which killing solves nothing. She announced her intention in a much retweeted tweet:

Aren’t we all getting a little tired of killing? Annihilation of the other side, revenge, scorched earth, an eye for an eye that leaves the whole world blind; vengeance may feel good in the moment, but it has never been a real solution. But foregoing vengeance doesn’t mean that justice must also fall by the wayside. Rachael Denhollander, a lawyer, devout Christian, and survivor of Larry Nassar’s abuse, points out that media loved to highlight the words of forgiveness that were part of her victim impact statement. However “they didn’t focus on the fact that I was also there asking for the judge to give him the maximum sentence.” As represented in media and popular culture, forgiveness and justice are too often seen as mutually exclusive.

It is not an easy path that Taylor has chosen, but one that allows the conflict in her story to blossom with complexity. The most impossible difficulty surrounds the character of Minya. She is the one who rescued the infant Sarai and three other babies from the slaughter of the godspawn. To say that she is traumatized in an understatement. The violence of that day has trapped her. She is a prisoner in time, just as surly as she and her four rescued babies are physically trapped in a citadel, high in the air. Minya was four years old, or so, when Eril-Fain attacked. Minya’s gift is the essence of revenge. She traps the spirits of the newly dead. Ghosts are her puppets. She collects them, building an army against the day that she can use the spirits of the past to punish those living in the present. Minya is a woman in her early twenties, who by force of will alone has successfully raised the infants she rescued to their teenage years. But her single-minded pursuit of revenge has stunted her. Minya’s body is still that of the four-year-old child she was on the day of the massacre; she still wears the smock she wore on that day, though it is reduced to rags.

In the final moments of Strange the Dreamer, Taylor delivers one heck of a cliffhanger. The explosives expert, recruited by Eril-Fain, successfully blows up one of the large blue-metal anchors that holds the seraph-shaped citadel in the sky above Weep. Lazlo, desperate, leaps to steady the anchor and finds that he is no ordinary orphan, but one of the godspawn, carried away when he was born by the mysterious white eagle that has been haunting the edges of the story. Lazlo’s skin turns from brown to blue and he finds that he is able to control and shape the metal. As the angel tips, Sarai, standing in the palm of its hand, falls to her death, impaled on the spike of a fence. She dies in Lazlo’s arms, the first time they have touched outside of their dreams.

As we begin Muse of Nightmares, Minya’s gift becomes both the salvation and the despair of the newly dead Sarai. Minya catches Sarai’s ghost a moment before it wafts away to nothingness, but now Sarai’s will is free only at Minya’s pleasure. Minya holds all the power because she holds Sarai. Lazlo can control the blue-metal, making him the only godspawn who can travel at will between the citadel and Weep. Minya holds Sarai’s existence hostage. She offers Lazlo a choice: either take her and her army of ghosts down to massacre the humans of Weep, or lose Sarai forever. Minya is so certain of the rightness of her desire that she cannot conceive that rest of her family, the other three godspawn whom she rescued and raised, would have any problem with her request. But they are shocked. Lazlo cannot conceive of doing such a thing. Sarai would rather cease to exist.

Sarai spent her life trapped in the citadel, but she has the ability to enter people’s dreams. She knows more of the world than any of the other godspawn teenagers. Minya instructed her to shape the dreams of Weep’s citizens into nightmares as punishment for their crimes. But entering the dreams of humans has taught her compassion. She has intimate knowledge of the pain they suffered at the hands of the adult gods. She explores her own father’s shame, at first using it as a psychic bludgeon against him, later realizing that his nightmares needed no help from her.

At each decision point in the plot Taylor has a character propose killing as a solution. They are always overruled, not just out of compassion, but because she has woven the powers held by each character into a gordian knot of dependancies. This is the genius of The Muse of Nightmares. No one person can resolve this legacy of abuse and shame alone. The more characters isolate themselves, the more impossible their difficulties become.

As a ghost, Sarai has lost the ability to enter multiple dreams at once, though she discovers that if she is close enough to touch a sleeper, she can go into their dreams. She enters Minya’s dreams to see if she can free her from the nightmare of the massacre. Here Sarai realized how truly trapped Minya is. There is no way out. Minya relives the hour of slaughter again and again. Using the logic of dreams, Sarai builds new methods and means of escape. Each one fails. “Don’t you think I would have thought of that already?” Minya says. The murderous god-slayer is always coming. She is always trapped.

When Minya is alone, she repeats a mantra of apology: “They were all I could carry.” She has been trapped in a moment for fifteen years, gripped by horror, shame, and guilt. She cannot see it in any way other than through the eyes of a terrified four-year-old listening to the cries of children being killed because she failed to save them.

The theme of repeating loops of time surfaces over and over again: Taylor introduces another godspawn character whose gift is to create such time loops. Cycles of intergenerational betrayal and abuse pierce through rips in time and space, carrying the consequences of trauma from world to world. Survivors cannot simply let go and move on. They are literally trapped in time, and they trap others with them. Releasing someone from a loop they have created must be done with exquisite care; killing them would merely trap those who are entangled with them for all eternity.

The way Taylor resolves these conflicts is tender, poignant, and devastatingly sad. But there is also a great measure of hope in the final chapters. One sentence, hidden near the end of the book, ties the worlds of these stories to the worlds of the Smoke and Bone books. Blink and you’ll miss it. But make no mistake: this duology is complete as it stands. The surviving characters are determined to travel between worlds in search of others who were trapped as they were, hoping to free them. The arrogant hubris of the older gods may have led them to travel one world too far and let in creatures of chaos that will devour all. But this remains to be seen. Doubtless Laini Taylor has more books, and more incredible worlds, waiting for her to bring them out of her dreams and into ours.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.