Stephen Graham Jones begins Mapping the Interior, his haunting new novella, with a ghost sighting: Junior, a 12-year-old Native American boy, sleepwalks into the living room of his family’s home in the middle of the night, and upon waking sees his dead father passing through the kitchen doorway. It’s not a vision of his father as he was in life—Junior was only four years old when his father died, and he admits that he wouldn’t really be able to recognize his face. What Junior sees instead is a silhouette, the shadowy outline of a man wearing his tribe’s traditional fancydancer costume: feathered bustles, armbands, and headdress; elaborate beadwork; tall boots.

Junior interprets the vision as a sign that his father’s spirit has returned to watch over the family. It doesn’t matter that Junior’s father was never a fancydancer; what matters is that his father wanted to be one, at least according to the stories Junior and his younger brother Dino have been told by their aunts. These stories are all the confirmation Junior needs to believe that he has seen a ghost.

But has he really?

The question is never explicitly asked, or answered. Instead it hovers just beyond the page, implied in every ambiguity that Jones skillfully layers into the story. The uncertainty is pervasive, inescapable. It creates in the reader a subtle feeling of vertigo that echoes Junior’s own confused experience of being adrift in a chaotic world. When Junior says he saw his father’s ghost, we believe him, even if we don’t believe in ghosts. When the ghost saves Junior from mortal danger, meting out shocking (and mercifully unseen) violence, we shudder at the thought, even as we search for other explanations. When Junior finally confronts the ghost in a mind- and time-bending encounter, we can’t help but go with him on the journey. What we witness can’t be true, and yet it can’t be otherwise.

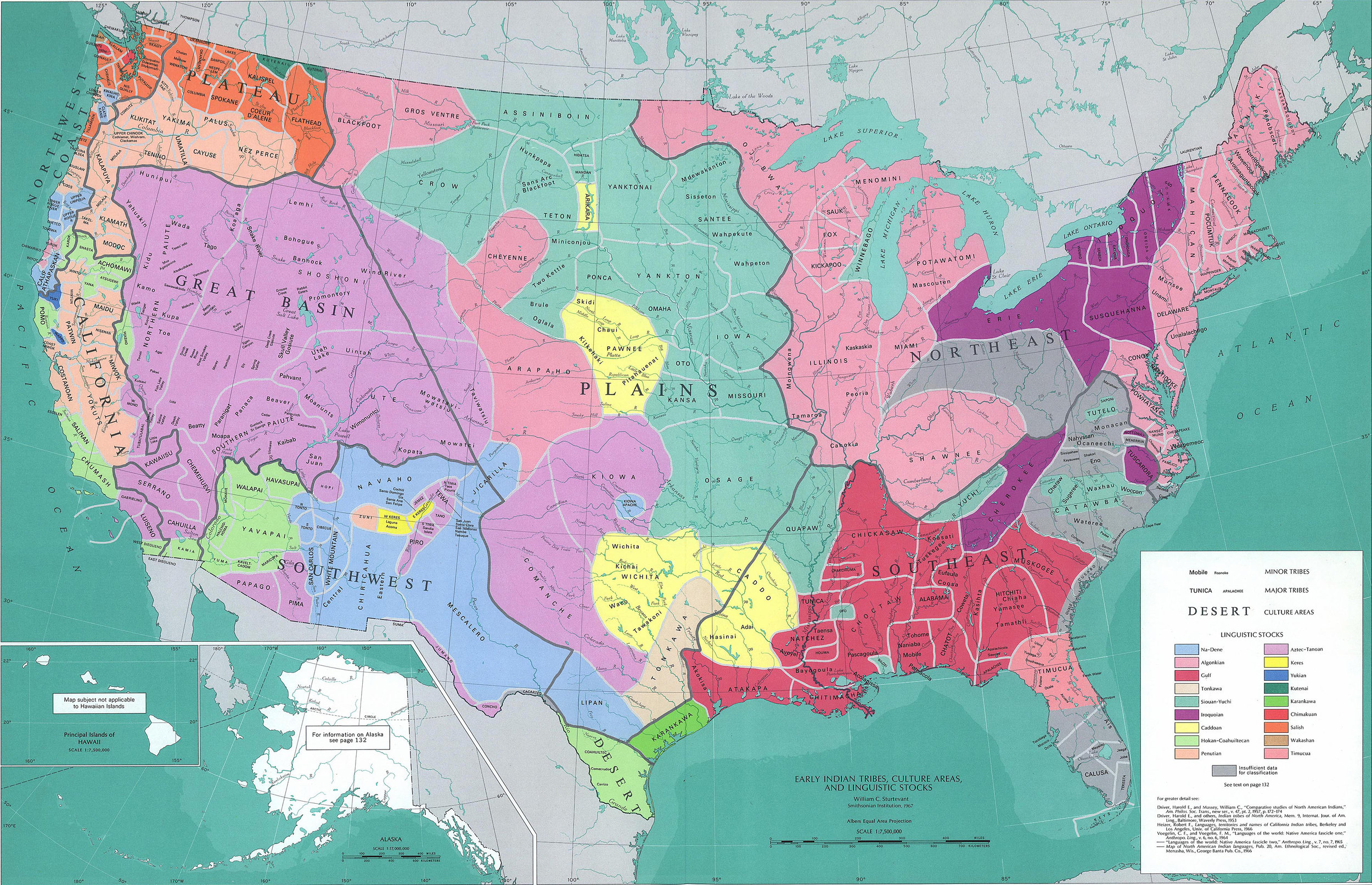

Like all ghost stories, Mapping the Interior is about the ways in which the past forever haunts the present. The consequences of every choice and action carry forward into the future, shaping the circumstances of those who come after us long after we are gone. We inherit not just our genes, but also culture and opportunity, or the lack thereof: legacies of trauma and failure are passed down as surely as skin tone, height, eye color, privilege, and wealth.

Junior greets his father’s return with hope rather than fear. The family has moved off the reservation and now lives far from the support of family and friends, cut off from their cultural heritage. Junior’s mother made the move to give her sons a better life, or at least a better chance at a better life. But despite the change of scenery, the family still lives in poverty; they are still scarred by the generational aftereffects of colonization and genocide; the brothers still don’t have a father. Worse, Dino has begun having epileptic seizures; he is, in Junior's words, “broken”. The family is alone, isolated, vulnerable. Junior is old enough to understand these things, even if he can’t put them into words. If his father has returned now, when the family needs him most, Junior reasons that it must be a good thing. He decides the ghost has come to protect them, and to make Dino better.

Junior clings to this hope. He searches for signs left by the ghost—a bead or feather, a smudge of face paint, anything that might constitute physical proof. With help from Dino, Junior measures each room in the house and sketches a scale map of the interior into his school science notebook. He is rigorous, methodical. He checks every square inch of the house; he retraces the ghost’s footsteps; he sits in the living room late at night with a jumprope wrapped around his legs to cut off circulation to his feet, hoping he will be able to “deadfoot” his way into the spirit world.

At first the search is fruitless. But then, as Dino’s seizures get worse, Junior discovers that his father’s spirit seems to be able to act in the world with frightening consequences—and that he, Junior, can too.

Tragically, perhaps inevitably, these consequences are not what Junior expected when he first saw his father’s ghost. To protect his brother, he must give up his own innocence and his hopes born of childhood stories where monsters are defeated and all wounds are healed and the world is made right again. This is how we grow up, he realizes. This is how we learn to promise ourselves that we will be different, to believe that we will be the ones to break the cycle and start a new legacy for our children.

But it’s never that simple. We’re not in control of the chaos, no matter what we believe.

Mapping the Interior took me back to my own adolescence, a time when I read horror stories and novels as fast as I could check them out of the library—Stephen King, Edgar Allen Poe, H. P. Lovecraft. The novella is part ghost story, part psychological thriller, part portrait of a young mind struggling to cope with unspeakable grief and existential rage. It’s the kind of story you stay up late for—because you want to, because you need to, and because there’s nothing quite like reading good horror at night. It’s also the kind of story that haunts you long after you’ve finished it.

In the end, Mapping the Interior doubles back on itself to reveal another, more troubling dimension of its tale about fathers and sons broken by the past. Junior’s childhood map of his family’s house isn’t enough to free him from the legacy of fear and disappointment he inherited. The past never dies. Old wounds never heal. The ghosts that haunt us are fickle things with unpredictable appetites, prone to weakness. As are we all.

Stephen Graham Jones, Mapping the Interior. New York: Tor, 2017.

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.