An interviewer once asked Eric Clapton about the change in his style from the blues purist we hear in his Bluesbreakers and Yardbirds work to the more psychedelic, hard rocker that appears in the midst of Cream. “What happened to prompt the change?” the interviewer wanted to know. “Jimi Hendrix happened,” was Clapton’s reply. Jimi Hendrix showed Clapton and generations of guitarists that there was so much more their instruments could accomplish than their adherence to tradition allowed them to discover.

N. K. Jemisin should have the same effect on any writer of speculative fiction who reads her words. We are not using out imagination fully. We are not thinking enough about the possibilities and implications of our worlds. We must have more potential than we are tapping, because it wouldn’t be fair if Jemisin is the only one capable of fitting such a density of wonder onto every page, right?

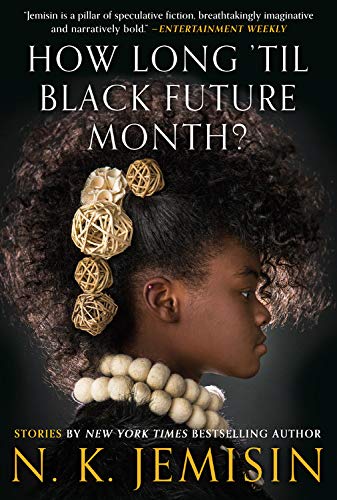

N. K. Jemisin

How Long ‘Til Black Future Month?, N. K. Jemisin’s new short story anthology, puts the depth of her imagination on full display. If three consecutive novel Hugos have not convinced you she is a modern master, this collection will bridge the gap. Each of these stories is its own invention. There is little reliance on convention. Sure, you will find the occasional dragon or witch in these stories, but they rarely fill the role you would expect them to.

Instead, we get stories like “The City Born Great” where a homeless street artist builds a connection to New York City so strong he is bound to play literal midwife as it births itself into a new era. His relationship to the city takes him a long time to recognize. He’s mostly just trying to get by and coexist with a populace that doesn’t much care for him, and he responds with earned disdain. The mentor who has found him, who has played this role in another time, at another place, tells him he must overcome his disdain. Out of all of them, the city chose him. And all of their lives depend on him. To which the narrator’s internal response is:

Maybe. But I’m still hungry and tired all the time, scared all the time, never safe. What good does it do to be valuable, if nobody values you?

It’s a feeling that a lot people can find all too relatable and it’s a recurring theme in Jemisin’s stories and novels. Her heroes are often outcasts and cast offs, people devalued by the predominate culture and power structure. She puts them under the treads of oppression and then asks them what they intend to do about it. There is always something which can be done about it. Sometimes this requires the harshest of self-sacrifice. The narrator of “The City Born Great” eventually learns what he himself is made of.

There is a force which does not want the city to survive its birth. The enemy force’s minions, when they appear, manifest as cops. Even before the minions arrive, every cop in “The City Born Great” is already a threat to the narrator. They have a knack for picking him out of a crowd and bringing him low. But as sadistic as he knows the real cops can be, with these he can feel “something immense and wrong shifting in my direction.” If you think you might know how the encounter with these minion cops will turn out, I’m betting you do not. If you think you know, when you are two thirds of the way through this story, how the climax is going to play out, you most certainly do not. That is one of the joys of being in the deft hands of an imagination like Jemisin’s. You quickly give up trying to guess ahead and instead let her current take you where it will – backwards up the waterfall and other directions you were not expecting to go. Be sure, it makes sense as you’re going there. Your willful suspension of disbelief will not be abused. All of Jemisin’s worlds plunge deep and feel true.

“The City Born Great” is the second story in How Long ‘Til Black Future Month and the one where it clicked that I would not be reading the sort of fantastical stories I was used to. It was also where I understood that these stories would not only be different, they would be better. I was not disappointed. The stories continue to satisfy even as they change sub-genres. There is fantasy and science fiction, of course, but there is also steam punk and cyber punk and horror and stories that will stun you so hard you forget to categorize them.

I can’t wait to re-read this book. And I’m eager for more writers to read her and absorb her influence and inspiration. I’m eager to see what her influence will be and I’m sure her influence is already being felt. Her influence will definitely be strong in the coming decades, but it might be difficult to spot. She does not linger in a single world like Tolkien or Lovecraft. But she does make you wonder what stories we might have if Tolkien had written more and if Lovecraft could write. What I hope to spot in others is the boldness of her themes — her disregard for the clever story that has nothing to say. In the center of her adventures are the hard realities of our own world and the implicit question to her readers: What do you intend to do about it?

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.