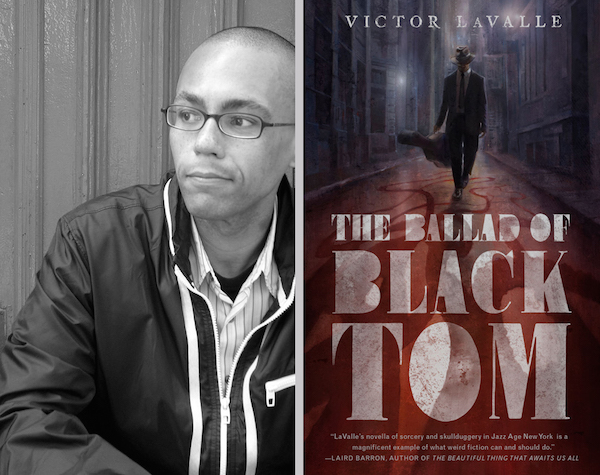

Reading Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, I thought a lot about performativity. Performativity, in the work of theorist Judith Butler, is the repetition of individual actions that “cite” prevailing cultural discourses related to identity. Think of it this way: consider how we coach children to understand color in gendered ways. Blue is for boys; pink is for girls. The entire color spectrum is demarcated along gendered lines, and as adults, we tend to dress in colors that are “appropriate” to our gender, thereby manufacturing not only our gender identities, but also our sense of self.

Butler’s writings about performativity primarily focus on gender; however, her framework is useful in considering how LaValle presents race in The Ballad of Black Tom. The protagonist, Tommy Tester, is an adept performer, not necessarily of the blues music he feigns at playing, but of varying roles that signify what society understands to be blackness. A down-and-out musician, a gangster, an invisible man, a docile “Yes” man, Tommy Tester performs all of these characters to eke out a living for himself and his ailing father. Well versed in the requisite costumes, gestures and speech patterns, he sees his performances as manipulation:

“When he dressed in those frayed clothes and played at the blues man or the jazz man or even the docile Negro, he knew the role bestowed a kind of power upon him. Give people what they expect and you can take from them all that you need”

Notice LaValle’s choice of the word “need” as opposed to “want”. The Ballad of Black Tom takes place in early 1920’s New York and is full of the racial injustices characteristic of the time, and unfortunately, some that persist into the present. Against this set of segregation, exploitation, profiling and police brutality, there’s a 20-year-old black man performing every shade of blackness projected onto him. As LaValle’s use of the word “need” suggests, Tommy Tester’s performances are about survival:

“Becoming unremarkable, invisible, compliant— these were useful tricks for a black man in an all-white neighborhood. Survival techniques.”

The risk of performance, however, is to lose sight of oneself, to mistake the performance as oneself. When Tommy Tester loses the only thing that anchors him to an authentic experience of himself, he creates a new role, Black Tom, and through it channels a rage that threatens to destroy the entire world. I don’t want to give away too much; it’s a pleasure to discover the story as LaValle unravels it. It will suffice to say Tommy Tester’s rage is monstrous. In his wake, blood and bodies accumulate.

I hadn’t felt that uncomfortable about a character since reading, at the age of 14, Richard Wright’s Native Son. Both characters, LaValle’s Tommy Tester and Wright’s Bigger Thomas, engendered tremendous anxiety in me. I realize now that these characters challenge my performance of blackness. They spur me to contemplate how I manufacture my identity.

Throughout my early teens, I tried on a few different shades of blackness. I gave speeches about black nationalism that were inspired by Marcus Garvey. I attended seminars by thinkers affiliated with the Nation of Islam who taught me about pervasive systemic injustices, showed me in graphic detail the destruction of black bodies, inculcated in me a fear for my safety. There was even a period of time when I played at being a Black Panther and donned a beret.

Then I came out.

The powerful social forces that police identity were quick to inform me that gayness was incompatible with blackness. They said gayness belongs to whiteness, and any black person who professes to be gay is brainwashed by the oppressors. What ensued was a horror story of epic proportions, and my survival was rooted in performing a new script, one that was written by Martin Luther King Jr.

U.S. history tells us that black bodies are sites for victimization, exploitation and destruction. Black self sacrifice and moral integrity are eventually rewarded; black rage and self determination by violent means are immediately eliminated. In performing the blackness that claims the moral high ground, I was afforded opportunities to escape the violence and threats of homelessness that characterized my youth. What would have happened if I had chosen to rage?

LaValle allows Tommy Tester to rage and be transformed by his anger into the predator society expects him to be. I allowed myself to take the punches and be transformed by the violence into something society expects of black bodies. These transformations remind me of W.E.B. Du Bois’ account of double-consciousness:

“…the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”

Adding Butler’s work around performativity, I would argue that not only are we viewing ourselves through others’ eyes, but the performance of our identities is also constructed around how others perceive us. This is especially evident in Tommy Tester’s transformation into Black Tom:

“Everytime I was around them, they acted like I was a monster. So I said goddamnit, I’ll be the worst monster you ever saw!”

The Ballad of Black Tom is good is so many ways. It’s entertaining, full of taboo magic, and the bad guys get their just desserts. It subversively reimagines a story by a virulent racist and installs a powerful black man as its protagonist. More importantly, it provokes contemplation about the scripts we choose to perform and the identities we manufacture based on others’ expectations. Months after finishing the book, I’m still questioning if there’s a Tommy Tester lurking within me?

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.