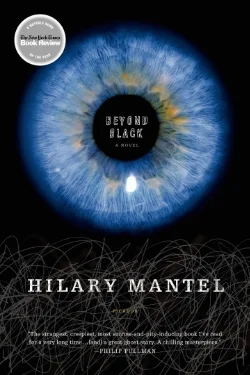

Before Hilary Mantel double-Bookered with her Cromwell novels, she wrote the horror-comic novel Beyond Black (2005), a terrifically bleak study of a much-abused medium, Alison, and her hard-nosed stage manager, Colette. In Beyond Black, the Spirit World is all too real, if surprisingly trivial, and Alison does commune with the dead, though this does not exempt her from the canny guesswork and little frauds that keep a good psychic stage show working. Meanwhile, Colette books the dingy civic buildings and village halls in the urban sprawl along London’s orbital freeway; she performs sound checks, hands the mike around the audience, haggles drinks from the house, and wrangles the motor lodge receptionists; if she isn’t entirely free from doubt, still she sees enough to know Al is sparing the “punters” the grimmer details of the afterlife.

Mantel is a deft manager of register in her genre-bending novels, and in Beyond Black she never lets the supernatural conceit or her satirical eye run away with the tone. She does this, firstly, by grounding us in skepticism: The first long scene, in which we follow Alison working the crowd in an Enfield bar, has us scrutinizing her every blandishment—just like the punters—to see if we’re really supposed to believe she talks to ghosts.

“This lady—I see a broken wedding ring—did you lose your husband? He passed quite recently? And very recently you planted a rosebush in his memory.”

“Not exactly,” the woman said. “I placed some—in fact it was carnations—”

“Carnations in his memory,” said Al, “because they were his favorite, weren’t they?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said the woman. Her voice slid off the mike; she was too worried to keep her head still.

“You know, aren’t men funny?” Al threw it out the audience. “They don’t like talking about these things; they think it means they’re oversensitive or something—as if we’d mind. But I can assure you, he’s telling me now, carnations were his favourite.”

But gradually, enough hits pile up for us to trust Alison is not merely a fraud; that her foul-mouthed, dick-exposing “spirit guide” Morris is regrettably real; and that the supernatural is something to be taken seriously. Except—except we also realize that the dead are just as mundane as the living, and the spirits relaying messages through Alison really do want to tell their loved ones to see the dentist about that ache, or compliment the woman in the back on her refurbished kitchen. In a terrific set piece, Alison and her colleagues in the psychic arts manage the surge of clientele after Princess Diana’s fatal accident; everyone, especially the lonely and unremarkable, feels drawn to the royal passing:

Diana is the Queen of Hearts; every time the card turns up in a spread, this week and next, she will signify the princess, and the clients’ grief will draw the card time and time again from the depth of the pack. ... If you look hard you will see her face in fountains, in raindrops, in the puddles on service station forecourts. Diana is a water sign ... She’s just the type who lingers and drips, who waxes and wanes, breaths in and out her tides; who, by the slow accretion of tears, brings ceilings down and wears a path into stone.

Alison’s clients come to her out of landscapes of insignificance—including Colette, once a punter herself, still picking over her stultifying failed marriage—looking to the supernatural for answers, connection, meaning. A kind word from Di, or even just a nod from a dearly departed on their kitchen unit, will assure them their lives are at least a little noteworthy. But what Alison will never tell the trade is that “airside” has little significance to offer. When Di does manifest—oh, but I can’t give it away. It’s deathly funny, and sad, and lyrical. And I trust no one more than Mantel to use the word ‘fuckerama’ without breaking poignancy.

Richard Bergh, Hypnotic Séance (1887)

But the heart of Beyond Black is Alison’s efforts to rid herself of Morris and his friends, a group of spirits who, we learn, she’s known since her nightmarish childhood. Poverty and ridiculously grim abuse pervade her vague memories, confused even more by her gifts—as a child, she was never quite straight on who, of the many foul men coming through the house, was alive or dead at any given moment. It’s not clear to Al even today whether the unseen woman her mother kept talking to was a ghost, or an insane delusion, or maybe the bodiless head she saw floating around the bathtub out in the yard. (Yeah, when Mantel wants to go dark, by golly she goes dark.) What is clear is that Morris was one of these johns and his cronies are still following Alison around—the fiends, she calls them. Mostly, they complain about the quality of local bars' fish-’n’-chips; but they also torment Alison, molest her in her sleep, and hint darkly at the horrors they once inflicted on her.

Louis de Breton, "Astaroth," from J.A.S. Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire Infernal (1863)

This breed of fiends would have been familiar to medieval or Elizabethan audiences, say, but are less so today. While Chosen Ones are all the rage in modern diabolical narratives, the powers of Hell used to be just as interested in the souls of peasants and tradesmen; Satan, with a hundred million demons at his disposal, can afford to be a democratic tempter. In his royal Daemonologie, King James I described a cosmic order in which any poor soul could be the centerpiece of high drama between God and the Devil:

Either such as being guiltie of greeuous offences, GOD punishes by that horrible kinde of scourdge, or else being persones of the beste nature peraduenture, GOD permittes them to be troubled in that sort, for the tryall of their patience, and wakening vp of their zeale ... .

[But Satan wants] one of two thinges thereby, if he may: The one is the tinsell [loss] of their life, by inducing them to such perrilous places at such time as he either followes or possesses them, ... [and,] so farre as GOD will permit him, by tormenting them to weaken their bodie, and caste them in incurable diseases. The other thinge that hee preases to obteine by troubling of them, is the tinsell of their soule, by intising them to mistruste and blaspheme God: Either for the intollerablenesse of their tormentes, as he assayed to haue done with Iob; or else for his promising vnto them to leaue the troubling of them.

As orthography improved, and Enlightenment skepticism turned its side-eye on religious superstition, the democratic Devil fell out of favor, but the idea has never left the Gothic imagination. Think of the lengths the Enemy goes to in Confessions of a Justified Sinner, or “Young Goodman Brown,” or The Exorcist, to torment or trap one ordinary soul.

Des Teufels Netz, the Devil's Net, from the Codex Donaueschingen (1441), shows fiends after everyone, from pope to farmer.

For all that popular demonology had horrific repercussions—the deeply misogynist witch crazes, misdiagnoses of mental illness as “possession”—there is existential comfort in this notion that angels and demons are contending over your soul, however small. Now every decision you make is charged with supernatural dimensions; dragging yourself out of bed for another workday, bickering with your spouse, haggling with the grocer, it all adds up to eternal reward or punishment, with the Devil’s fiends trying to nudge you in the wrong direction at every turn. The business of living is actually a fight against the hordes of Hell.

This is the sort of supernatural significance that Alison’s punters are looking for and, as Mantel recognizes, will not find. Their wasteland of freeway junction towns, garden store car parks, and littered marshes is invincibly atheistic. But as Alison maneuvers, wheedles, and extorts her way past her fiendish familiars, a secular-humanist version of this popular demonology emerges: each person has personal demons to confront or flee, and it’s worth each person’s time and attention—and ours—to participate in that drama, no matter how big or small the soul. It’s a deeply literary thesis, and far from new. The marvelous thing that Mantel has done with Beyond Black is to draw that connecting line between character study and supernatural drama, boldly, to show that "trivial" does not signify "pointless." Little wonder, that such a grim book feels so optimistic as it ends.

Read Similar Stories

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.