In continuing support of speculative fiction in the Rocky Mountain Region, Fiction Unbound attended Denver's annual speculative fiction extravaganza, MileHiCon 48, and reviewed its fund-raising anthology, Adventures in Zookeeping, in which Unbound Writers Lisa Mahoney and CS Peterson published stories.

Report from MileHiCon 48: Showcase of Colorado Writers and Fans of Speculative Fiction -- Lisa Mahoney

MileHiCon is Denver’s annual science fiction and fantasy convention. While there are movies playing day and night, an art show, science-oriented discussions, and fans in costume, many of the lectures are geared toward how to write and get published.

A few highlights from the convention’s opening day included writing panels like “Great Opening and Ending Lines” and “Worldbuilding: Things Every Author Should Know.” Other programs focused on hard sciences such as genetic engineering and climate change. There were also interviews of celebrities by successful writers in the field: Denver based Jason Heller interviewed Guest of Honor John Varley about his Gaea Trilogy. Here are more details about programming.

“All the interviewers and moderators that I was involved with were very prepared, and asked intelligent questions. Some of them were so intelligent that I couldn’t answer them.”

This year and last I attended sessions by the great Connie Willis, a Colorado author who has won 11 Hugos, 7 Nebulas, a Locus Award and more. This year Willis presented “Five Ways to Give Your Writing Razzle-Dazzle” while illustrating each point with movies most of us in the audience knew well. Her first suggestion was to ensure the story has “the money shot” -- a scene with sensory fireworks which could be visceral, hilarious, horrific (like the stomach-popping Alien), transcendent (the fight in the willows in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) or something completely over the top (Slim Pickens riding the atom bomb in Dr. Strangelove). Other suggestions for adding razzle-dazzle included using literal metaphors, like a raven croaking “Nevermore.” Writers can also heighten contrasts. Instead of putting an ordinary person in an ordinary place, try something outrageous like by throwing a Las Vegas showgirl into a convent. Her examples were engaging and illustrative, and if you have the chance to attend her lecture at MileHiCon next year, do take advantage of the opportunity.

Unbound Zoos -- Theodore McCombs

You might have noticed: we’re terribly proud to have two fellow editors at Fiction Unbound, Lisa Mahoney and C.S. Peterson, included in the anthology. Each offered an adventurous take on the very word, ‘zookeeping,’ Lisa teasing new life out of the gawking condescension implied in that first half, ‘zoo,’ and Catie tackling the bittersweet impossibility of ‘keeping.’

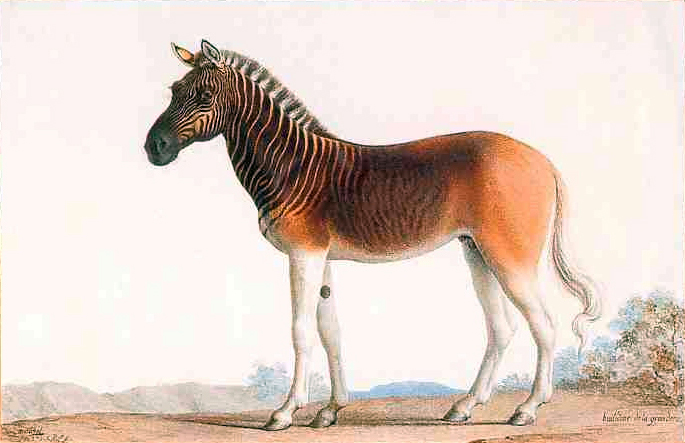

A painting by Nicholas Marechal of King Louis XVl's Quagga, a subspecies of zebra that went extinct in the 1870's, from his royal menagerie in Versailles. (Painted in 1793, when Louis himself was extinct.)

In Lisa Mahoney’s “ReligioZoo,” the displays house hermits and priestesses from far-off worlds conquered by a galactic empire. In the new Empress’s benevolence, the zookeepers are tasked with converting these heretics, but the ReligioZoo’s cynical owner Siv knows the real money lies in his visitors’ crude sense of superiority over these caged mummers. From its beginning, zoos have been an imperial project, with their roots in the ancient royal menageries, meant to display the breadth of the emperor’s power through the exotic animals captured, shipped and caged. It isn’t too far of a stretch to show humans; imperial Britain has done it before. “The ReligioZoo” shows Siv’s prisoners rising above this enforced animality by the grace of their faith, “savage” though it may be; can Siv’s business partner Rustain do the same?

CS Peterson and her jeweled black quaver at MileHiCon 48. Photo by Sam Knight.

In C.S. Peterson’s “The Jeweled Black Quaver,” the zoo is an expansive wildlife preserve on a distant planet, where conservationist rangers like Callie and Rom nurture the endangered black quaver back into a thriving population. The jeweled black quaver is something precious--with its big emerald eyes and haunting evensong, tourists travel light-years just to see and hear it once in their lifetimes--but maybe “conservation” isn’t the right word. For the black quaver flourishes in a very specific ecosystem: volcanic aftermath. The preserve must be destroyed, cycled through life and death and life again, and competing species must be culled, to keep this one beautiful species. There’s something stoic, melancholy and restorative in contemplating the quaver as we look at, say, the loss of the Great Barrier Reef or the white rhino, and the enormous task (is it an impossible one?) of holding on to the beauty we see in the world.

Everywhere You Go, There You Are -- Mark Springer

Bern, Switzerland, has kept live bears on display in the city since 1513, if not earlier. Today the bears are housed in a natural-habitat enclosure, but before 2009 the animals lived in open pits where spectators could easily view them.

Years ago when I visited the city, the bears were still in the most famous of these pits, the Bärengraben. The Bärengraben is hardly medieval, not like the enclosures of centuries past, but to my delicate American zoo-going sensibilities it was a shock. The pit’s design made no attempt to conceal its purpose: the confinement of living creatures for the fleeting amusement of passers-by. It wasn’t for conservation or research; it was about power and ambition, a declaration of supremacy, a reflection of a deeply rooted and long-held cultural belief that humans stand apart from the natural world and are masters of it. Or so it seemed to me.

I watched the bears for signs of their discontent. I saw none. The bears were indifferent to the crowd above, untroubled by the fact of their confinement, perhaps even unaware of it. One slept in the shade; another lay on its back in the sun. Clearly they didn’t share my interpretation of the cultural significance of their situation. My discomfort said more about me and the way I saw the world than it did about the the bear pit itself, whatever its failings.

I recalled this experience as I read Adventures in Zookeeping. The collection abounds with creatures fantastic and familiar, and with elaborately imagined enclosures and habitats. The zoos (loosely defined) range from delightfully anachronistic steampunk-literal to pointedly allegorical, from extraterrestrial to extra-dimensional, from visions of the afterlife to waking nightmares. The variety on display here is worthy of its own taxonomy.

Please don’t feed the bears. The Bärengraben, Bern, Switzerland, circa 1880.

And yet, for all the speculative settings and beastly beasts, the stories in this collection are more about the keepers than the kept. Basilisks, spectral shivors and jeweled black quavers notwithstanding, what kept me reading were the familiar human concerns that emerged again and again—fear of death (“Zookeeper’s Dilemma”), family estrangements (“Eternity’s Ark”), the dehumanization of labor in a capitalist economy (“Picket Line”), the unintended consequences of environmental exploitation (“Corpse Flower”), the personal cost of revenge (“The Nightmare Menagerie”), to name just a few. At its best, Adventures in Zookeeping reminds us that the thing we’re most likely to find in life, whether we’re working in a fantastical zoo or watching black bears sunbathe in the Bärengraben, is a reflection of ourselves.

Here There be Monsters -- CS Peterson

Zookeeping is chock full of speculative stories that exhibit their own unique twist on the concept of a zoo. There are a few more I’d like to feature in the categories of unexpected zoo and the horror of the unknown. As Mark has pointed out above, zoos often reveal more about the keeper than the creature. In these stories the juxtaposition of human hubris and the nature of the unknown produce a delicious chill.

In “Glass Fairy” a child stomps her foot to get her way. She wants a pretty glass fairy she sees in a shop. Her mother consents rather than fight, but when the mysterious old shopkeeper hands the little girl her prize, it comes with a warning. Another warning goes unheeded in “Niwotlei Fund Raiser.” The zoological park is closed and the cages opened so that big money donors can watch an intergalactic blood sport. Where warnings are ignored things go terribly wrong.

I teach Latin. For several lessons I have students translate the descriptions of the beasts found on the Hereford Mappa Mundi. It is a medieval map of the world known to people of western Europe in 1300. The unknown hovers at the edges and monsters abound.

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.”

That fear permeates “The Menace of Markenshire” where the Keeper balances his duty to preserve and hunt when an unknown predator finds its way into the preserve. The fear itself becomes the monster in “Ari’s Song.” If you were aware, at every moment, of the vastness and mystery of the universe, would your sanity survive? One may make a bargain with Cthulhu as in “All in a Day’s Work,” but the horror that has been release will color all that comes after.

There is a hopeful encounter with the unknown. In “The Fourth Lemur,” humans, or at least one specific human, may finally have bridged the gap between species. But the cost may be evolution into something other than human.

The authors of Adventures in Zookeeping have done a great job of providing readers an entertaining smorgasbord of human reflection.

Adventures In Zookeeping Editor Sam Knight and Publisher Villainous Press

Adventures in Zookeeping was edited by Sam Knight and published by Colorado Springs publisher, Villainous Press, as a fundraiser for MileHiCon. Sam Knight is distribution manager for WordFire Press, senior editor for Villainous Press, and author of children’s books, many short stories and two novels. Villainous Press publishes trade paperback books, hardcovers, graphic novels, comic books, paperbacks and ebooks mainly within the speculative fiction genre.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.