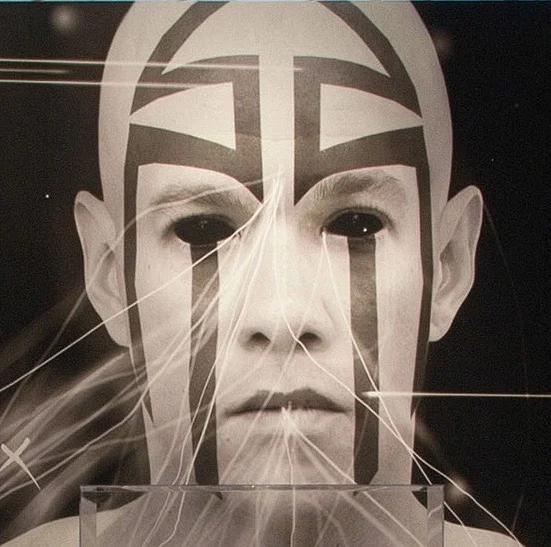

The figure of an aeronaut stands at the exhibition entrance, equal parts Po'pay and Dark Jedi. Photo: CS Peterson © 2016.

Creative works in the post-apocalyptic and dystopian genres aren't really about the future; they are about possibilities, the many parallel universes of what might be. Often they are implicitly framed as warnings. Speculative art, regardless of medium, has the unique ability to stick its toe in the waters of a possible future while we are in the process of choosing what our own future will be. It gives us a chance to look at what has happened in the past alongside what is happening in the present, so that we can consider what might happen in the future if history should repeat itself or continue on its present course.

In "Revolt 1680/2180," on view at the Denver Art Museum until May 1, 2016, artist Virgil Ortiz casts the sweeping saga of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt five centuries into the future, where history repeats and the cast of characters takes on mythic proportions. (Star Wars uses this strategy too.) Over the past ten or so years, Ortiz has expressed his imagined future in disparate pieces: a screenplay, fashion, photography, graphics, painted bodies, and figures that grew out of the traditions of Cochiti pottery. He has displayed excerpts from the story at smaller exhibitions and gallery shows in the past, but "Revolt 1680/2180" marks the first time a substantial group of his pieces are on view together. The effect is to create a speculative world every bit as enthralling and meticulous as any in film or literature. Truly, this is storytelling unbound.

The image of Translator floats above Tahu, leader of the blind archers, and the conquistador who blinded her. Installation view of Revolt 1680/2180: Virgil Ortiz, © Virgil Ortiz.

The exhibition opens by introducing viewers to the real-life historical and cultural tropes that ground Ortiz's speculative vision. Saints and Sinners is a series of Roman Catholic saints made in the fashion of monos, hollow clay figures made in Cochiti around the turn of the 20th century. These figures were traditionally used for social commentary and sold to tourists. In the exhibition, the saints sit on niche-like shelves flanked by Gothic angels and protected by an alter rail.

The figures of the saints are meant to represent the intense conflicts surrounding religion that led up to the Pueblo rebellion. At that time in history, the Pueblo region of the American Southwest was struck by a long drought, which began around 1670. Five years into the drought, the Spanish colonizers began arresting Pueblo religious leaders as scapegoats, putting them on trial for "sorcery." A few were executed before the Spanish relented and released the remaining prisoners. Po’pay was among those released. Five years later, he would lead the Pueblo revolt against his former captors.

An Aeronaut and Mopez, the cardinal headed messenger, look out from an unquiet landscape. Installation view of Revolt 1680/2180: Virgil Ortiz, © Virgil Ortiz.

In Ortiz's work, the narrative of the Pueblo revolt is split into parallel fictional spirals, sequences that are linked across time and space, 1680 and 2180. There are several characters that provide connection between past and future. The foremost is the character of Translator, an androgynous being that is not bound by time or space. Somehow this feels natural in a world where we see the worst tendencies of human nature repeat themselves again and again. The pattern of corruption, the seduction of power and the horrors of war show up as universals across post-apocalyptic literature.

Tahu - the blind archer 2180. Revolt 1680/2180: Virgil Ortiz, © Virgil Ortiz.

Tahu, the leader of the blind archers, is depicted both as a superhuman character of the past and in 2180 as a time traveler and a cyborg. In the fictionalized past, Tahu and her friends won an archery contest against conquistadors and were blinded by the jealous Spaniards. In both the past and the future representations, Tahu has suffered physical violence, but persists in resistance, using abilities that contradict her physical limitations. Her name is a term of respect used by grandmothers for their granddaughters and granddaughters for their grandmothers. It provides connection to generations of women in both directions: the past looking forward and the future looking back.

We then step firmly into the post-apocalyptic future with The Venutian Soldiers, heirs of the 1680 Puebloans. They are eight feet tall, with superhuman strength and magical tech. This time, the land they fight for has experienced environmental catastrophe in a nuclear war. They wear gas masks, protective gear and walk in a hostile landscape. In the Velocity series, figures dive through wormholes, carry laser blasters, melt between multiple dimensions. The figures of the revolt in 2180 have a transhuman, alien appearance. Are these cyborgs? Beings from the stars?

“Well, maybe it’s really the question of, are there aliens? Probably, but I like to think that they are just future versions of ourselves that have come back to help and provide guidance. Angles, devils, aliens - maybe they are all just the same thing.”

Virgil Ortiz (b.1969), Cochiti, Steu, 2014 and Cuda, 2014. Clay slip and wild spinach paint. Private collection.© Virgil Ortiz.

Yet the existence of conflict in the future implies cultural survival and a persistent link from the past to what may come. All the aeronauts in the eVOlution series are twins. The characters of Cuda and Steu, specifically, have a yin and yang quality to them that implies the balance of dual perspectives carrying on the wisdom that elders, in the far past, would have hoped to give to their children. They pilot ships that transverse time and space, escorting ancient ancestors-elders, to where they are needed.

The character of the Ancient Ancestor is presented out of time, in the same space occupied by Translator. The Ancestors, and their twin escorts, are the past untethered, a repository of knowledge that future generations can draw on for resilience. They carry with them the patterns of survival in the face of overwhelming odds.

The only drawback to this exhibit is its transience. I wish that this compelling world could be more easily accessed by speculative fans. But if you do find yourself in Denver before May 1st, come experience Ortiz’s vision, before it is scattered to the wind once more.

The reflections of Cuda, the aeronaut; Tahu, the blind archer; and Mopez, the cardinal headed messenger, watch over the figures of two Venutian soldiers. Installation view of Revolt 1680/2180: Virgil Ortiz, © Virgil Ortiz. Photo: CS Peterson © 2016.

SOURCES:

Ortiz, Virgil, and John Lukavic. "Revolt, 1680/2180: Virgil Ortiz." (Denver, CO: Denver Museum of Art.)

Lukavic, John. "Curating Virgil Ortiz: Revolt 1680/2180." Personal interview. 19 January, 2016.

Engañador, Daniel. “Who Was Po’pay? The Rise and Disappearance of the Pueblo Revolt’s Mysterious Leader.” New Mexico Historical Review, Spring 2011, Volume 86/Number 2.

Sando, Joe S. and Herman Agoyo, editors, Po'pay: Leader of the First American Revolution, Clear Light Publishing, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2005.

In a world on the brink of collapse, a quest to save the future, one defeat at a time.