Amanda, Catie (CS Peterson) and Christie (CH Lips) got together to discuss recent retellings of the Rapunzel story and muse about why so many women get locked in towers when we write fantasy.

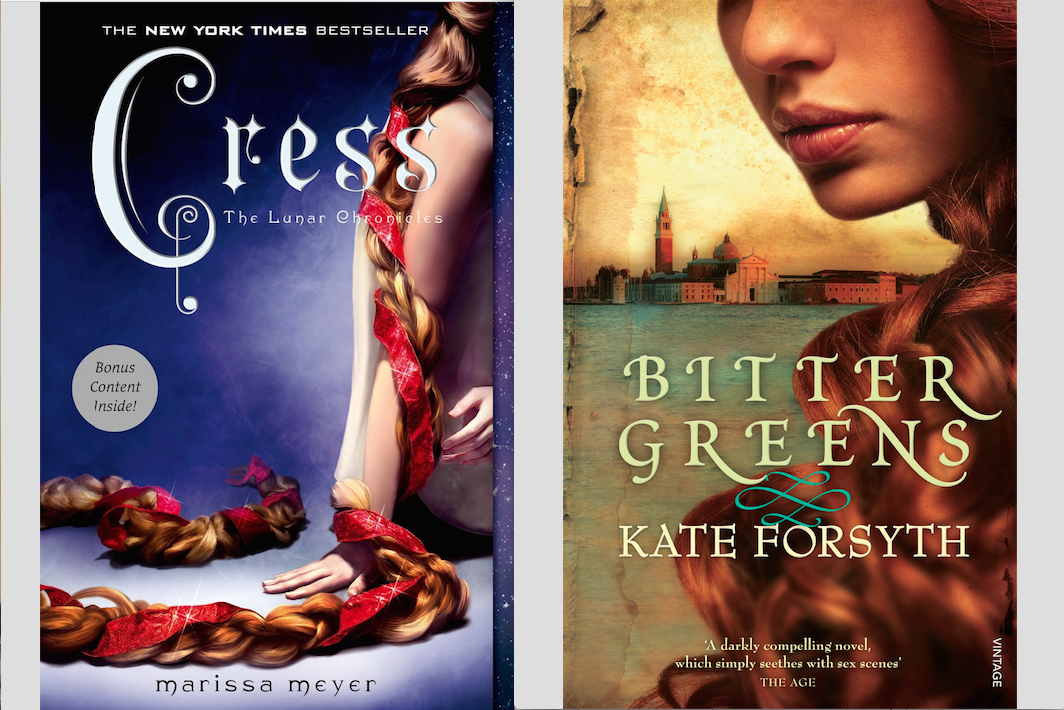

Kate Forsyth’s Bitter Greens is a braided retelling of the Rapunzel story from three perspectives. The first is Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de La Force, who pens the first version of Rapunzel in 1698 while confined to a convent by her cousin, the French King Louis XIV, as punishment for writing an excess of scandal. The other two story lines follow Rapunzel herself and Selena Leonelli, the witch who confines her.

Cress is the third book in The Lunar Chronicles by Marissa Meyer, a 5-book series that weaves together several traditional fairy tales and sets them in the far future. Meyer re-imagines Rapunzel as Cress, a teen computer wiz locked in a satellite orbiting Earth and forced to hack into the Earth’s systems and spy for Levana, the evil Lunar Queen.

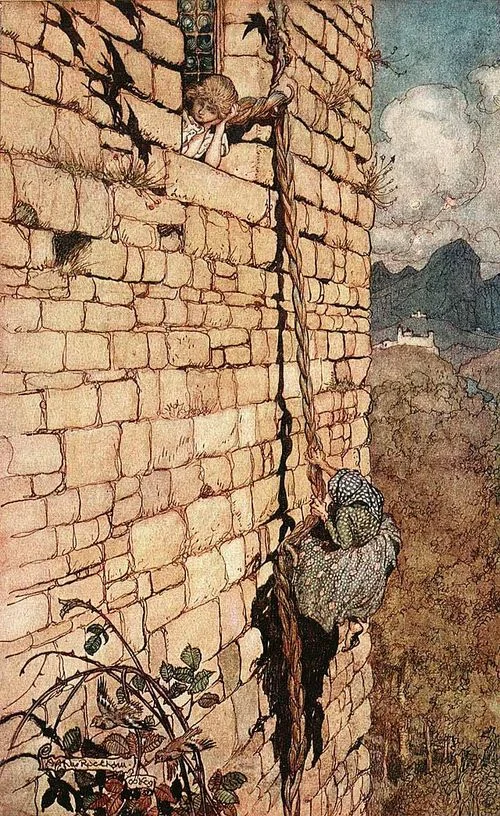

CS Peterson: I enjoyed Bitter Greens. It was a bit of a bodice-ripper, but in terms of historical fiction, Forsyth is really exploring women locked up, be it in towers or convents. Her characters develop a voice despite the restrictions placed on them. Charlotte-Rose is put in a convent/prison for using her voice and her voice is what gets her out. She has an epiphany listening to another nun, Soeur Sarafina, tell the story of Rapunzel in the garden. Charlotte-Rose bargains to get her writing tools back so she can regain her voice. The thing that rescues Rapunzel in every iteration of the story is her voice, not allowing herself to be silenced. She starts singing her story from the tower and that is what finally rescues her, what brings help.

Amanda Baldeneaux: Which is why I can respect Bitter Greens. Rapunzel’s hair is like Charlotte-Rose’s story, it’s her way out. I want to give the books props for having Charlotte-Rose not be a conventional beauty. We rarely get away from that with other female protagonists in fantasy.

CH Lips: In Cress it’s her smarts—her hacking—that’s her voice in the world. And when I think about the original Rapunzel story it’s not about when she’s in the tower, its about how she got there and how she gets out. So Cress really works for me in that she doesn’t stay in the tower very long—I mean by like page 50 she’s out.

AB: I also loved that Meyer wrote the character of Cinder as part Asian. Meyer is getting away from the pretty-white-girl syndrome. Wolf is a Lunar, but described as a Mediterranean-looking guy and Princess Winter is black. Cool. In Bitter Greens, Forsyth seemed more bound to her source material, except for Selena Leonelli, the witch.

CSP: The witch’s story was the best. The witch, Selena, is brutalized as a child. As an adult she is consumed with a thirst for vengeance and by the desire to control time and aging. In the end she seeks redemption. It’s a real hero’s journey.

CHL: I agree. She’s interesting, she’s doing things, she has agency. Selena Leonelli makes shit happen. However, although I’m all for hopeful endings, I felt the fates of the three women in Bitter Greens did wrap up a little too neatly.

AB: I think that’s actually a commendable point for Bitter Greens. (Spoiler alert!) Two of the main characters end up unmarried, on their own and satisfied: one running the garden and one running a Paris salon for the arts. The third fits the fairy-tale ending though, happily married to a wealthy Medici prince and singing opera.

CSP: Yup—no worries for our little Rapunzel, since the historical Medici’s were such a happy family (not).

CHL: I’m really interested to see what Meyer does in the Lunar Chronicles with the blood, though. In Bitter Greens, the witch wants Rapunzel locked in the tower is so she can bathe in the blood of a virgin and keep herself young. In Cress, the witch takes blood samples from her prisoner, that have something to do with a Lunar plague. Both authors chose to keep the bloodthirstiness of the witch in their stories. I never really heard that part of the story as a child.

AB: Me neither, and it’s different from the Into the Woods witch wanting to protect Rapunzel from the big bad world. But that brings up the question of where these things come from—girl-on-girl crime—it takes two to keep these societal constructs up. Propping up institutions that imprison women because maybe you feel safe in the tower? When I was a little girl watching Disney I thought that was what I wanted, I wanted this prince to come along and save me.

CSP: Though there is a real precedent from history. If you don’t lock up your women, they’re going to be attacked. It feeds the stereotype of barbarism and lack of self-control in men, too. Speaking of the princes I have to say I love Thorne’s reaction to Cress’s hair. He is the “prince” character in Cress.

AB: I saw fan art of the moment and I loved it. I love that Meyer has lots and lots of fan art up on her site. I spent a good long while perusing it because I really liked the characters. I love that Meyer is a big FireFly fan. When I’m reading Cress, I keep picturing Cinder as Kaylee. ‘Cause mechanic Kaylee, mechanic Cinder.

by lostie815.deviant... on @deviantART.

CSP: Really? I'm not sure I agree. I was thinking Red, the organic-farming Red Riding Hood character, had more of Kaylee’s sass. Cinder is more insecure, constantly doubting herself.

Jewel Staite as Kaylee Frye in Firefly.

CHL: That’s something that bothered me in all the female characters in the Lunar chronicles. Cress does that too, “I can’t do anything!” says the girl who’s hacked the entire world. The self-image thing. The guys do not come across that way to me in this book—except Kai. He’s the exception.

CSP: Since we’re talking about the guys and Ted brought up Freud and Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment, we should mention how the symbol of the tower plays out in these stories.

AB: Like I said—girl-on-girl crime here. One woman locking up another in a male symbol as a concrete statement of ownership. The witch takes on this male symbol as her own power status. She has literally taken the power of men. She has her own tower, her own autonomy, her own money and she’s gained it all through sex.

CSP: And she’s bathing in the blood of a virgin locked up in a tower because she has to maintain her beauty in order to maintain her power. She brutalizes her own “daughter,” piercing her with a thorn and drawing blood every month that she visits in order to prop up her borrowed “male” power. Should we call this the Rapunzel Complex?

AB: Ha! The Rapunzel Complex, why not? In our own novels, we all are writing, in some literal way, about women trapped in towers. And we’ve all struggled with having our female characters be something other than a victim. I didn’t realize that I had a bit of Rapunzel in my story until you all pointed it out. My protagonist, Rosalyn, lives as a prisoner in her house on top of a mountain.

CHL: So many women feel this threat, so how do you get out of it? My protagonist is totally locked in a tower by her father. It’s a struggle to write about women because, obviously, most women aren’t going to be able to fight their way out. Cinder is a cyborg so she can literally fight, but that’s special. It’s interesting to try and write a story of the woman breaking out of the tower. Amanda, you have a goddess-like character, so she has power.

CSP: And you have a goddess, Christie. She has powers, but she doesn’t know what they are yet. And Amanda’s character has the same thing. Her powers are part of her discovery. None of us did that consciously. In the opening of my novel I have an imprisoned woman dropping her baby over the side of a tower. The image just caught me in the gut.

CHL: It’s interesting that both Amanda and I are using nature for our protagonists to express their power, but Catie, your protagonist is more along the lines of a traditional guy hero. She fights with a sword.

CSP: That’s why I put her in pants right away. Fighting in a skirt just leads to lots of bodice ripping and that’s not where I’m going. I’m trying to head more in the direction of True Grit.

AB: Hey, don’t dis the skirt! My gal’s still powerful in a skirt. That can work, too.

CHL: Yeah, I got my girl into pants right away, too. We’re both in the great Shakespearean tradition—once you get a girl onstage, you’ve got to get her into pants as soon as possible or she can’t do anything.

CSP: I’ll respect the skirt, but I have to say it really bothered me in Bitter Greens that Charlotte-Rose was always riding side saddle. I was in fear for her life with every jump. I kept yelling at the book, “Get your other leg over the horse, girl!”

AB: That’s a valid point though, how putting on pants diminishes femininity in fantasy (think Arya and Brienne of Tarth in A Song of Ice and Fire). The witch and Charlotte-Rose both have their femininity questioned because they can be self sufficient. So, how to be girly and powerful?

CHL: All of these fantasy pieces are about fighting and swords—that’s where the climax is. It’s a battle, and women—most women—aren’t physically able to best a bunch of guys with a sword unless they have some magical power or a titanium hand like Cinder. As authors we are challenged to come up with other ways for our female protagonists to be powerful.

CSP: We’re in unexplored territory in terms of trying out new ways for female protagonists to be in fantasy literature.

AB: So it all goes back to the pen being mightier than the sword. The way Rapunzel leaves the tower is through the power of her voice. This is a great time to be writing.

Carmen Maria Machado’s genre-bending memoir is a formally dazzling and emotionally acute testimony of an abusive queer relationship.