In our continued excitement over last weekend’s Denver Comic Con, Unbound Writers CS Peterson, CH Lips, and Amanda Baldeneaux wanted to explore speculative fiction novels that utilize comics as plot elements, metaphors, and commentary on the novel’s world. Reading Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven and Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, the Unbound Writers daringly plunged into both the future and the past, exploring how inclusion of the humble comic elevated these works to high art, which is what we're all about around here.

Comics Within Novels & the Art of the Double Narrative

Amanda Baldeneaux: Both books had main characters who created comic books, and the stories of those comics were woven into the story of the characters. In Station Eleven, a near-future flu pandemic has eliminated most of the population, and one survivor has a copy of a comic book, Station Eleven, that tells the story of Doctor Eleven and his space station. In Kavalier & Clay, two young men create one of the first superhero comics, The Escapist, to play out their dreams of crushing the Nazi regime on paper.

The comics give us a deep look into the inner psyche of the characters who create them. Miranda, the artist and author of Station Eleven (the comic book), hails from a small island in Canada. As she makes her way through the outside world, she continues to return to her art and the story of a man who is unmoored, like herself, and searching for a new place to call home while a band of assassins, who rise up from the depths of the Undersea, attempt to thwart his plans and force him to return to the place he came from, even though the place they came from is damaged beyond repair. We get to see Miranda fighting herself and her own conflicting desires to return to who she was, and as the comic finds it way into the hands of a pandemic survivor, Kirsten, we see Kirsten connect intimately with the comic for the similar reasons.

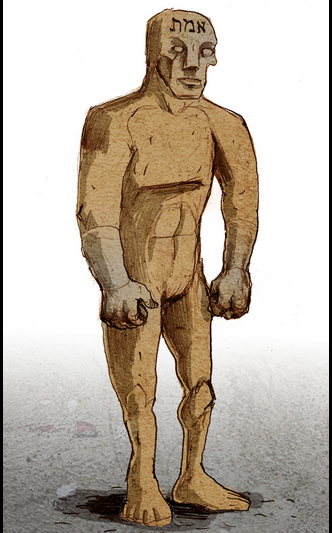

CS Peterson: What is fascinating to me is how both authors use fantasy as a metaphor to allow them to explore characters and events in the “real” worlds of the novels. Fantasy worlds are juxtaposed with “real” scenes. Characters from the comic appear in the “real world,” like Tracy Bacon, the actor who plays the comic book hero on the radio. The golem of Prague literally saves Joseph’s life when Joe hides in its coffin, and again as a character in the art Joe creates that gets him the job as an artist at Empire Comics. Not to mention his cousin's name is Clay-Man. In Station Eleven, scenes and dialogue from the comic are replayed with real characters. Kirsten and the Prophet, real survivors of the pandemic, mirror their comic book counterparts, Doctor Eleven and the assassins from the Undersea. Miranda, the comic’s artist, sits in her studio at the end of her marriage saying “Station Eleven was all around us.”

CH Lips: Both authors, Chabon and Mandel, merge the double narratives of comic book and “real” world together at the climax so that the characters in the story are acting out the comic book narratives. In Station Eleven Kirsten, the protagonist in the post-pandemic world, uses dialogue from the comic book in a life and death confrontation with the antagonist. At the climax of Kavalier & Clay, Joe Kavalier performs a superhero feat at the Empire State Building, even donning the Escapist’s outfit. Art becomes life. Reality literally embodies fantasy.

AB: And Chabon’s book is centered on art imitating both the real and fantasy lives of the main characters. The Escapist, who makes his debut on the comic book scene with a cover image of the hero punching Hitler in the jaw, is created by two young Jewish men against the backdrop of the looming second war. We get to live out their fantasies through their invented character.

CHL: In both stories this is the way comic book artists try to make sense of incomprehensible worlds. Miranda, the character who writes and illustrates the Station Eleven comic books, is caught in the shallow world of Hollywood movie stars. After a particularly inane dinner party where she realizes her husband is having an affair, she creates an assassin from the Undersea, who leaves a note beside his victim—“We were not meant for this world. Let us go home.”—giving voice to Miranda’s own realizations about her life.

CSP: Somewhere in the middle of Station Eleven, I realized how many worlds were ending on each page, not just pre- and post-pandemic apocalypse. The end of a marriage is an apocalypse, as is the end of childhood. The islands where the protagonists grew up and the islands of Station Eleven stand in for the worlds that exist and then collapse, connected by bridges of memory and art. All worlds end, that is given.The interesting thing is the survivors have a choice: to pine for the past or move forward.

When Everything Else Is Gone, Does Art Matter?

CHL: I’d even say it’s the only thing that matters. The quote painted on the Symphony’s caravan and tattooed on Kirsten’s arm in Station Eleven says it all: “Survival is insufficient.” When Joe Kavalier has lost everything, he turns to art, creating a comic book novel that he keeps hidden in a room in the Empire State Building.

CSP: Art is the only way to preserve the world of the past. The art in both books reflects on the conflict of attitudes towards those “lost worlds” that occur in every life. The survivor crosses a bridge from island to island but the rebel comes riding up on a giant seahorse from the depths and launches the emotional attack: “We weren’t made for this new world, lets go back to the old, even if we have to bow to alien overlords.” Art, even the art of remembering, is the only way to reconcile these two desires.

CHL: Yes, and the people who see art only as an end to achieve money, fame or power miss the joy that is inherent in creating art. At the dinner party in Los Angeles on her anniversary Miranda is asked by one of the guests: “What’s the point of doing all that work if no one sees it?” Miranda says, “It makes me happy. It doesn’t really matter to me if anyone else sees it.”

AB: Joe also experiences this strong desire for a return to something that is more pure in memory than perhaps it was in reality: “It was all there—somewhere—waiting for him. He would return to the scenes of his childhood, to the breakfast table of the apartment off the Graben, to the Oriental splendor of the locker room at the Militarund Civilschwimmschule; not as a tourist to their ruins, but in fact; not by means of some enchantment, but simply as a matter of course.” As an adult, he’s finally able to accept that this return is not possible. The art he creates when he returns to live in the Empire State Building is for no one but himself at first. The art itself matters. It is a matter of life or death.

Catherynne M. Valente's salty collection of comic-book women in refrigerators, reviewed.