Warning: This post contains some mild spoilers for The Heavens, though the bigger surprises are left untouched.

Sandra Newman’s novel The Heavens starts out with a science-fiction conceit so instantly recognizable, it’s almost cozy. Ben and Kate are a young New York couple in love, in the year 2000. But in her dreams, Kate is Emilia, the mistress of a nobleman in Elizabethan England. And every time Kate changes the past in her dreams as Emilia, she wakes up to find her present slightly altered. The hazy vision of a city in flames tells Kate she is meant to use this power to prevent some future apocalypse. It’s Quantum Leap and “A Sound of Thunder” and The Terminator and The Lathe of Heaven, and even a little bit Shakespeare in Love. Because, we come to realize, Emilia is Emilia Lanier, the Dark Lady of the Sonnets, and that acerbic actor hanging around her, named Will, is—well, you-know-who.

That realization is the novel’s last cozy moment, however. We come to recognize that each time Kate changes the world, it gets a little worse. Ben and Kate’s families become unhappier with each revision, and their relationship more complicated. And, brilliantly, “worse” turns out to mean closer to our reality. In the first chapter, the president elected in 2000 is a Green Party candidate (and not Nader, either). Several dreams later, it’s President Gore; then it’s our own George W. Bush.

Time travel stories are hard. It’s easy to get bogged down in causality paradox and non-linear plot tricks, which create puzzles to obsess over more than good stories. At the same time, any unusual experience of time is so specific and anti-real that it’s hard to explore recognizable emotions with it. Newman executes her high concept with formal mastery, using alternating chapters in Ben’s point of view to showcase the effects of Kate’s Elizabethan intrigue, dramatizing her difficult navigation of the multiverse without sinking us in it:

But Kate just said, “What’s Exxon?” and then she seemed bewildered by his answer. She objected that oil was a thing of the past, because you couldn’t burn oil because of global warming. Ben said he thought oil still had a few good years left in it, and Kate said no, but then became unsure and said, “People still use oil?”

An even uglier example: “Kate frowned and looked unnerved, as if she might be hearing about the slave trade for the first time.” Using Ben’s perspective like this situates us in familiar human territory: distress at seeing a loved one declining, from Alzheimer’s or psychosis; or maybe, annoyance at that dreamy, artistic friend who can’t be bothered to notice the tragedies, big and small, that keep us earthbound suckers awake at night. “You could count on Kate to be more magical than you, to have to be more magical,” Ben thinks. “Everything about it got on his nerves.”

More profoundly, Kate’s estrangement from the injustices of our world defamiliarize and reintroduce those injustices: like Ben, we get an unkind shock when Kate doesn’t accept climate change or the slave trade as sad inevitabilities. And Kate’s comedown across increasingly worse timelines echoes that sense of comedown left-minded Americans experienced in transitioning from Presidents Obama to Trump. How could such hope and excitement curdle into even deeper, more bitter divisions? How did we move from utopian thinking to dystopian dread so easily?

In many ways, The Heavens is all about our suspicion of that progressive vision: the fear that, any time we try to engineer humanity into something better than it is, we only make the problem worse. Kate’s struggle, as she tries to save the world from itself, is the familiar desperation of watching that progressive vision fail, of realizing that “dream” is, after all, not just a word for the ideal, but also for the naiveté of fantasy:

She woke into a dream about Kate’s own life, in a timeline Kate had never visited before. … But the Kate in the dream was happy. She was sitting with Ben and it could all still be all right. And the people on the bus were happy; they were singing “No Pasarán” in gringo accents, pressing their protest signs to the windows, very happy because they believed in themselves. They thought they could make it all all right. Kate laughed, understanding, and sang until the song was over somehow and time had passed.

This tragic collapse and comedown is one of the dominant emotions of the Trump years, and, strange as these years are, it takes a speculative conceit like Newman’s to really get at the feeling.

Kate, especially as Emilia, is a terrific Elizabethan heroine, agile, perceptive, and sharp-tongued. But it’s in Ben that The Heavens becomes a fully human story, as his heroism runs up against its disappointing and undramatic limits. “He wanted to comfort her, but violently,” Newman writes. “He wanted to comfort her by saying, Would you stop this shit?” Like Carmen Maria Machado in “The Husband Stitch,” Newman deftly draws out the ways a good guy still is a guy. Patriarchy is corrosive, and even Ben’s best dreams of who he can be are steeped in it: “And out of nowhere, Ben was weak with love. … It was an energy that filled him and insisted he could save her. He felt powerful; he felt he was a wonderful person; he would do whatever it took. It was wrong and Ben was afraid of it.”

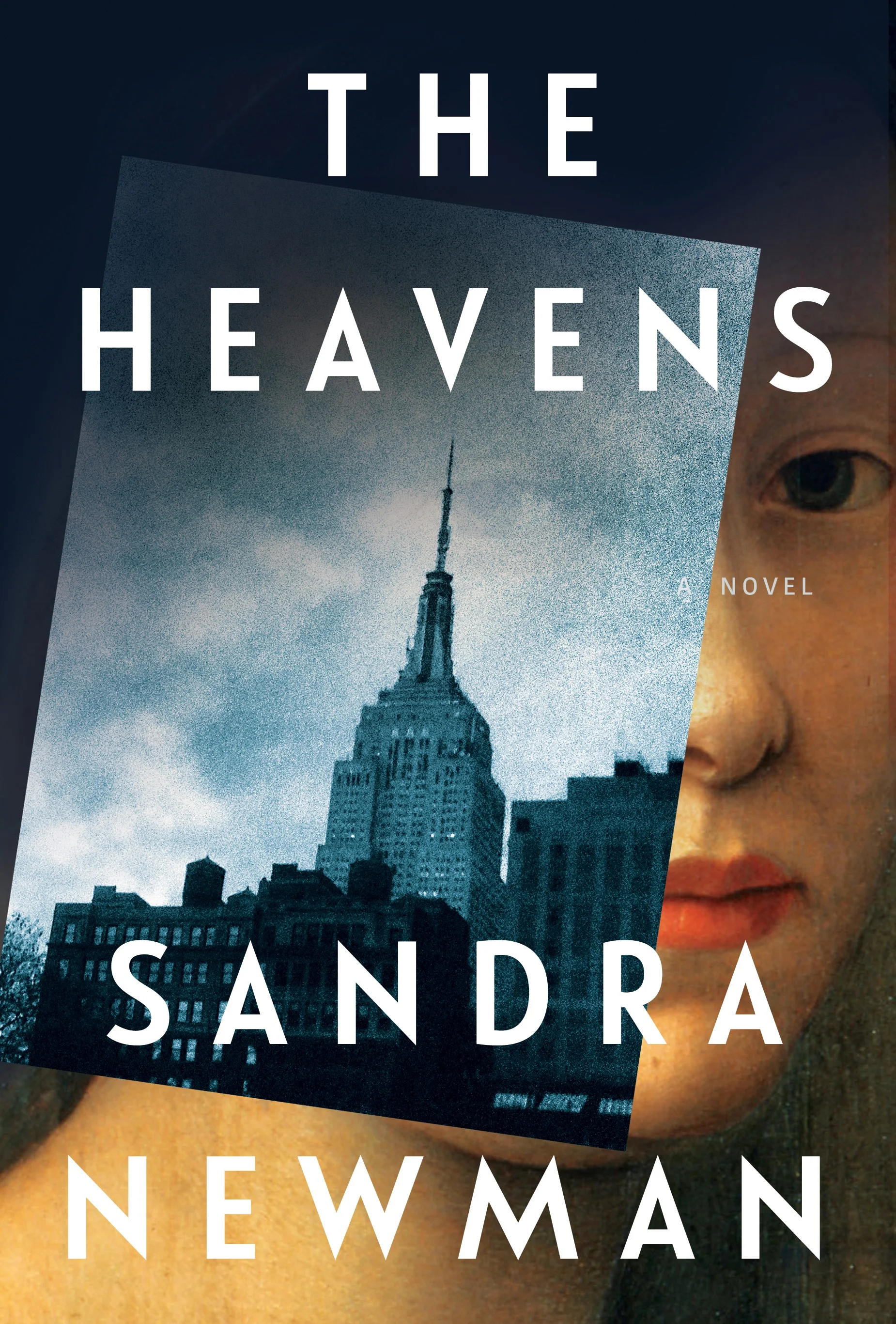

Sandra Newman from Grove Atlantic

Early in the first chapter, Newman flags the Great Man theory of history—and the butterfly effect—as thematic touchstones. How she thrashes this theory is too good, too perverse and fresh to spoil, but it ties together all the above themes of progressive fallibility, despair, and chauvinism in one shocking, yet exquisitely subtle scene. Like in the best speculative fiction, not only do the characters and plots have their arcs; so does the philosophy. The Heavens, out on February 12 from Grove Atlantic, is a daring and brilliant piece of speculative literary fiction, and a thoughtful, timely, and unnerving meditation on what it means to hope against hope.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.