Grocery store pumpkins are at high tide, and the aisles are stuffed with bags of fun-sized candy. Shorter days are bringing windy nights, apple cider, and scary stories told by the fire. In celebration of the season, we declare this “Crone Appreciation Week” here at Fiction Unbound.

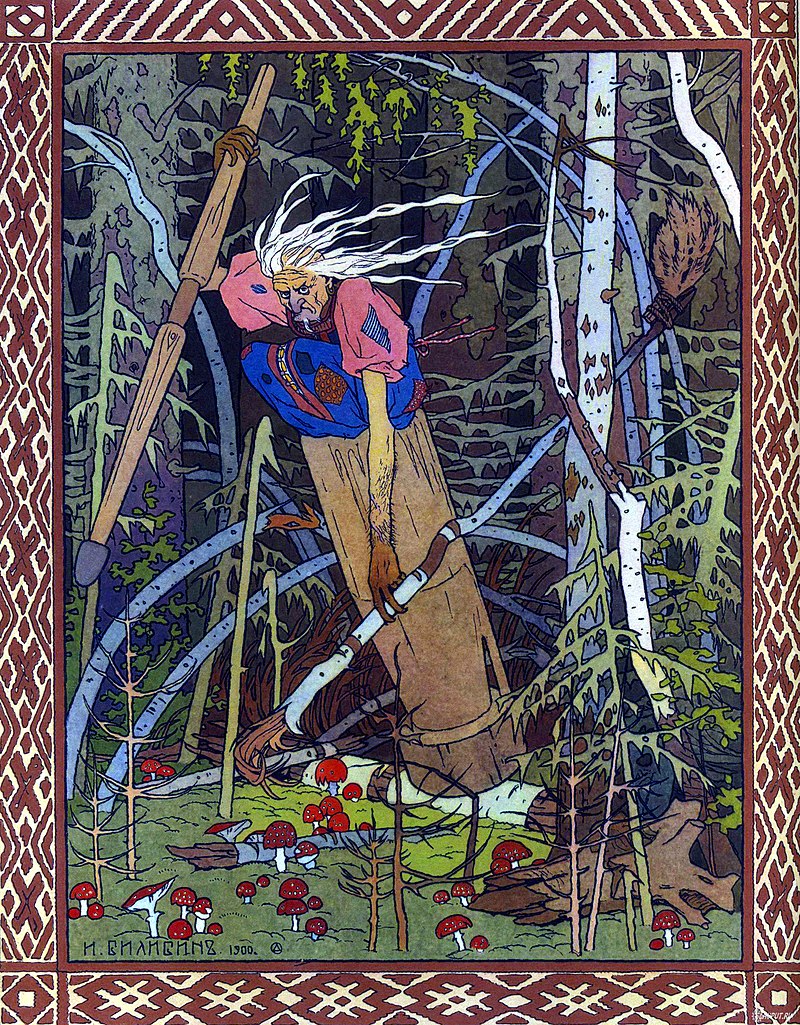

Baba Yaga is the archetypal crone. She is a slavic legend, an old woman, probably immortal, with iron teeth, who lives in a house that walks about on chicken legs and is surrounded by a fence of human bones. She flies in a mortar, the kind you grind herbs in, steering it with a pestle. Sometimes there’s a broom involved to sweep away her tracks. She’s rumored to eat children, but only little boys (that’s one way to smash the patriarchy).

Baba Yaga wins our Crone of the Year Award, as well as our hearts. It was little contest, given her unwavering iron nose, iron will, and commitment to shaping the female leaders of tomorrow. Jane Yolen’s updated novel-in-verse about the archetypal crone, Finding Baba Yaga, is well-timed to come out on October 30th, at the height of the season of the witch.

CS Peterson: Baba Yaga stories often begin with a young person wandering from home and losing their way in the woods. Yolen updates the legend by beginning with Natasha, a contemporary teen, running away from a deeply dysfunctional life at home. There is no Hansel and Gretel romance here. Natasha spends days and nights sleeping rough, as a homeless runaway. The reality of her situation is gritty and hopeless. Things get better when Natasha turns off the beaten road and enters the woods. But beware, as Yolen warns in the poems that bookends her novel:“You think you know this story. You do not.”

“this is a tale

both old and new,

borrowed, narrowed,

broadened, deepened,

rethreaded, rewoven,

stitches uneven”

The line starts off a little like the bride’s rhyme of what to wear: “something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.” But blue is missing in Yolen’s verse. All sorts of fairy tale expectations veer off to take different paths in this portrayal of the old crone in the woods.

Amanda Baldeneaux: This book is my first formal introduction to Baba Yaga, a character I’ve only met prior on the periphery of Western fairy tales. In Yolen’s version, we meet a woman who lives both in the present and out of time, a woman who can be found by taking one wrong turn off the interstate but who can come across occupied castles and monarchies as easily as she would a 7-11.

CSP: Yes! When Natasha enters the woods the story definitely takes a turn for the fantastical: walking houses, lessons from a magical crone on flying through the air. But the gritty undercurrent from the first poems remains, just below the fantasy surface. In Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, the protagonist tells two stories, one of animals, and one of human cannibals. Which story is true? Well, Pi asks, which one do you prefer? Yolen’s Natasha could ask the same of the reader. Does she really wander into a wood and apprentice herself to a magical crone, one who is at least as dangerous and unpredictable as Pi’s tiger? Maybe. Which kind of story do you prefer? There is power in a fairy tale to overlay trauma and transform it into something that is possible to hold in the mind. We are built of metaphor and narrative. As Yuval Harari theorizes in Sapiens, storytelling is the defining characteristic of our species, the thing that literally makes us human. Narrative is the tool we use to make sense of the chaotic world. Humans live in a dual reality; one exists objectively, the other we create in our minds to understand the first. Yolen’s book is about the power of words to create reality. It’s a meta-fairy tale, aware of its own magic.

AB: In Carrie Messenger’s “Reports from the Village of C, Near the Great Forest of Codru” (Pleiades, Summer 2017), Baba Yaga appears in a similar duality of fantastical overlaid with the very real famine facing Soviet Russia prior to WWII. Messenger’s tale is a combination of Hansel & Gretel and Baba Yaga stories. Here, the witch that the children find was once an educated woman, rejected by her family in a time of famine because of her age and supposed uselessness. The children find her inside her candy-hut with chicken feet, and true to the original Hansel and Gretel tale, overtake her to save themselves from the oven. Unlike the original, the story continues, following the children into adulthood. Hansel suffers PTSD the remainder of his life, while Gretel becomes a well-read, high-ranking official in the Soviet Army. At least, until the past catches up with her and she no longer feels compelled to be part of a society she can’t fully trust, and so wanders off into the woods. Which brings us back to Natasha. Both stories are ultimately about how the young maiden in the maiden-mother-crone triptych becomes the wise woman in the woods.

CSP: The transformation of a woman through these three phases is all over Yolen’s book. When Natasha leaves, her own mother has the flavor of Baba Yaga about her. A metaphorical fence of bones grows up between Natasha and her mother. Natasha suddenly sees her as old, “her face skull-like.” Natasha calls her a witch and flees. In Russian, baba means “grandmother,” while yaga carries different shades of meaning in the various languages where the crone’s stories live. In all of the translations, Baba Yaga embodies some kind of existential terror. She is Old Mother Mortality, who lives deep in the forest. Baba Yaga is relentless, irascible, unpredictable, irreverent, vengeful. She has a foul mouth and eats children. She is bones and skulls and a companion of Koschei the Deathless. But she is also ambiguous. Sometimes Baba Yaga helps heroes, takes them on as an apprentice. Sometimes she eats them.

AB: In Yolen’s version, Baba Yaga does take Natasha on as an apprentice, along with the beautiful Vasilisa. One of my favorite lines of Yolen’s is, “She wants them to learn to steer,” from the poem “Feisty Girls.” Baba Yaga isn’t just taking in strays, she’s running a leadership training program for young women, teaching them to “steer” their own destinies. Natasha is not just learning to be the designator of her own fate, she is a protégé, whether she likes it or not. The world she came from had no place for her, so what other options does she have?

Koshchey the Deathless, the only one who can give Baba Yaba a scar. Ivan Bilibin from 1902.

CSP: At one point she does have the option not to enter Baba Yaga’s house. Once Natasha takes the turn off of the road and into the magical woods, Yolen does wax a bit idyllic. Natasha finds “tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, Sermons in stones, and good in everything.” (As You Like It IIi) But then she enters Baba Yaga’s house and that is where the action is. Some say Baba Yaga is the personification of a wild storm. In Yolen’s book, she is the storm of life itself. Metaphors abound. The turning of the house is enough to make your head spin. But, as with life, if you expect the house to move in a predictable way, you will constantly be off balance.

AB: Natasha’s father would never approve of her new home with Baba Yaga in the woods, “a house that can walk about has rooms full of sand, weeds, seedlings, burrs.” There’s a heavy focus on the book of clean versus unclean. Natasha’s father is a pastor, but not a kind one. He and Natasha’s mother argue constantly and ignore Natasha at best, and wound her with critiques when they do focus their attention on her. Baba Yaga’s house is like an active mind, collecting things, filling itself. The house has nature on the inside, and that means a wilderness full of ideas and thoughts; these are not things Natasha’s rigidly religious father would approve of. The house reminds me of the Tardis in Doctor Who.

CSP: I so want to see a Doctor Who episode that includes Baba Yaga! She shows up in so many places. There are no less than two versions of Baba Yaga stories in Bernheimer’s updated anthology of fairy tales. In one, a woman dies but does not understand that she is dead. She runs into Baba Yaga who sets her straight. In another, Baba Yaga has a beautiful pelican child and Audubon appears as the seducing prince who kills Baba Yaga’s daughter so he can paint her.

AB: Another recent Baba Yaga publication is Taisia Kitaiskaia’s collected advice columns “Ask Baba Yaga,” referenced by Yolen in her forward as the inspiration for her book. I expected these to be light-hearted and silly, but instead fell in love with Kitaiskaia’s beautifully nuanced “advice” from Baba Yaga, who spoke through her in natural metaphors of sometimes harsh but always painfully on-point verse. In her forward, Kitaiskaia said she felt Baba Yaga speaking through her, meaning she also, at least temporarily, became the archetypal figure. Through her words, Baba Yaga showed herself a cryptic oracle, both poignant and empowering:

CSP: Yolen’s story-in-verse tracing a young woman’s growth into her own power couldn’t be more timely. Line up to get your copy on October 30. Read thoughtfully, put some stew in the crock pot, and go vote while you wait for it to cook.