Ever wanted to curl up with a good tale, really sink your teeth into a ripping plot, and be finished before the fire dies out? Then pick up more novellas. E-books and e-zines can publish works of any length or price and are not subject to printed paper limitations that demand 300-400 page novels. This week we take a peek at the year’s best novellas. The Unbound Writers threw the titles of the Hugo Award nominations for Best Novella into a hat and passed it around. We found they were all worth a read.

Lisa Mahoney: Penric and the Shaman, by Lois McMaster Bujold and This Census-Taker by China Miéville

Lois McMaster Bujold Photo by Kyle Cassity.

Ms. Bujold is one of the most awarded science fiction and fantasy writers of all time. The worlds and galaxies she creates are rich in many details, including religions, like Penric’s World of the Five Gods: the Mother, Daughter, Son, Father, and Bastard, Penric’s god.

Besides a good story, this novella is a meditation upon divine omnipotence, fate, free will, and the efficacy of prayer. An investigator chasing a shaman accused of manslaughter believes he needs a sorcerer, Penric, to help him capture the accused. But a local preacher asks whether the Bastard sent Penric to help him in answer to his prayers:

“Then perhaps it’s not your skills as a sorcerer that are wanted but your skills as a divine.”

Penric was taken aback. “That... wasn’t a subject I spent much time on at seminary. It’s rather a horrible joke if so.”

Gallin half-laughed. “That’s no proof it wasn’t from your god.”

Penric helps the shaman regain his powers to help free two ghosts. Yet it is the Son of Autumn who claims the sundered souls whom the shaman and Pen rescue, not the Bastard. Everyone wonders if their own ideas and choices effected this rescue, or whether it was all a set-up, pre-ordained. Bujold, like many brilliant philosophers before her, doesn’t supply an easy answer.

Lisa previously reviewed This Census-Taker, by China Miéville in January of 2016

...Unlike in Miéville's longer works, in This Census-Taker, the imagined world’s broken political systems and the magic that may or may not saturate the boy’s rickety home aren't gradually clarified to us because they are not central to the nine-year-old narrator's circumscribed world. The boy lives on a mountain slope enough like our world that we recognize it, but the low level of technology, plastic trash, broken bridge and gangs of orphans hint at some apocalypse in the recent past. The boy’s father is a refugee from another country, having fled from something unspecified. He makes keys that seem to solve people’s difficulties, but because the boy has grown up in this world, he is not as curious as an adult stranger would be. We, following through the eyes of the boy, never need the exact magical or political systems explained to us. They are not what is important. What is important is that this is a story about a boy whose father has a violent temper and about the shift in the boy’s relationship with him as his fear of the man increases...

Amanda Baldeneaux: Every Heart a Doorway, by Seanan McGuire

Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children is a bit of a misnomer in claiming the word “home,” for children who come to Miss West’s school are as far removed from home as Dorothy was from Kansas. Literally. All of the boarding school’s students have returned (some more than once) from other worlds. Some, like Nancy, found a door to a ghostly underworld hidden in a cellar. Some, like twins Jack & Jill, found their doorway inside of a trunk in the family attic. Unfortunately for these portal travelers, the onset of adulthood or breaking a few rules or finding themselves in mortal danger lands them back in our world, sometimes temporarily, or, the more likely scenario, forever. Miss West’s pupils haven’t fared well back on Earth and long for re-entry into worlds of nonsense and logic, magical realms where those too touched by the rationality and caution of age are no longer welcome. Homesickness for the places they feel they truly belong bind the residents of Miss West’s school tightly together, the school their only refuge from a society that rejects their stories of travel as psychosis and lies. The school, while never truly home, promises acceptance and safety. At least it did, until students start turning up dead. As suspicious eyes turn to Nancy, the new girl with an affection for all things dead, she has to help root out the real murderer before she herself is killed, and all her journeys ended forever.

Seanan McGuire drops readers into the ever-after of children who’ve crossed thresholds out of our world and returned to exile and misunderstanding, making us wonder if that fever of homesickness felt in a corner of our own hearts isn’t the remnant of some forgotten adventure of our own childhood? And maybe, if we work hard enough to shine a light on the thing that tries to kill our sense of magic and wonder through adult sensibility, maybe we, too, can re-find our doors and finally go home again.

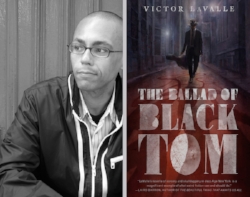

Jon Horwitz-White: A Taste of Honey, by Kai Ashante Wilson, and The Ballad of Black Tom, by Victor LaValle

There’s something queer about Kai Ashante Wilson’s A Taste of Honey. It begins with a foreign soldier calling out to a passerby, “Hey beautiful.” The passerby is a man, and there’s a moment of ambiguity as to whether the compliment was deliberate or mistaken. The soldier quickly dispels any confusion, “No - you, man. So beautiful!”

When the Unbound Writers divvied up the Hugo Award nominations for Best Novellla, “A Taste of Honey” fell to me by chance, and what a surprise to discover a story about queer characters, masculinity, and choices unique to the queer experience. A diplomatic mission between allied kingdoms brings Lucrio, a soldier from the visiting kingdom, to Olorum, the host kingdom, where he musters the courage to call out to Aqib, a beautiful youth passing in the night. Wilson imbues their initial encounter with tension: lingering touches and glances, things unsaid and things misunderstood, but all throughout, a budding connection. Within the space of ten days Aqib and Lucrio must decide how they will move forward with their connection, and of course, significant obstacles lay before them.

Looking at all of the nominated novellas as a group, it’s tempting to ponder what distinguished these works from the other 181 that were nominated by members of the World Science Fiction Society. Though I’m not a member of WSSF, a few noteworthy things distinguish A Taste of Honey. First, its subject matter enriches and diversifies speculative fiction. Like The Ballad of Black Tom, which I reviewed in October 2016. Wilson weaves a fantasy story around contemporary issues with which present-day societies are struggling. “A Taste of Honey” is redolent of societies’ struggles to accept and legitimize LGBTQ experience.

Second, it’s obvious that Wilson enjoys world-building. Class structures, nuances of language, and spirituality all accompany explanations of the more fantastic elements of the world, things like telepathy, telekinesis, clairvoyance, and uncanny scientific acumen. For the most part, his characters convincingly inhabit this world, and their actions and choices are firmly rooted within their socio-environmental context.

Lastly, Wilson structures the narrative of A Taste of Honey in such a way that time is unhinged. Lucrio and Aqib’s initial encounter is followed by a telling of events 11 days from their encounter, then returns to their first night, the day after, then speeds ahead again to the 13th day following their meeting. The narrative’s time is disrupted again when sections corresponding to Aqib’s age are introduced, and the initial encounter between Lucrio and Aqib is no longer narrative time’s anchor. The narration comes apart at its seams, and the reader must splice together Aqib’s life with fragile pieces, something Aqib is forbidden to do when he too discovers that the story of his life seems to be missing a key sequence.

The pay-off is worth it; the title hints at it. In an interview with the blog Push, Wilson discusses the usefulness of a title: it can save a writer many, many pages by focusing the reader’s attention. A Taste of Honey does exactly that while also weaving all of the narrative’s pieces of time together cohesively.

The competition is tight, and Kai Ashanti Wilson’s novella is an excellent contender. I’ll be munching on popcorn and eagerly awaiting the Hugo Award announcements in early August.

Jon Horwitz-White previously reviewed The Ballad of Black Tom in October of 2016

...Butler’s writings about performativity primarily focus on gender; however, her framework is useful in considering how LaValle presents race in The Ballad of Black Tom. The protagonist, Tommy Tester, is an adept performer, not necessarily of the blues music he feigns at playing, but of varying roles that signify what society understands to be blackness. A down-and-out musician, a gangster, an invisible man, a docile “Yes” man, Tommy Tester performs all of these characters to eke out a living for himself and his ailing father. Well versed in the requisite costumes, gestures and speech patterns, he sees his performances as manipulation:

“When he dressed in those frayed clothes and played at the blues man or the jazz man or even the docile Negro, he knew the role bestowed a kind of power upon him. Give people what they expect and you can take from them all that you need”

Notice LaValle’s choice of the word “need” as opposed to “want”...

Gemma Webster: The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe, by Kij Johnson

When Claire Jurat is enticed away from her studies at the Women’s College in Ulthar by the compelling Stephen Heller, her professor, Villett Boe, volunteers for the challenge of bringing her back before it’s too late. In this race against time and the foolishness of young love, the stakes are high. Claire is the granddaughter of a capricious sleeping god. If he wakes to find her gone from the dream lands he will surely destroy Ulthar and its idyllic surrounds.

To say that Villett Boe is a non-traditional adventure protagonist is an understatement. She is a 55 year old Maths Professor from the city of Ulthar. As a youngster she was a far traveler of the dream lands. Not only is she an expert in the realms and monsters of the world she has also encountered the irresistible dreamers from the waking world, aka our Earth, in the form of Randolph Carter--H.P. Lovecraft’s protagonist from The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath. The dream lands are Lovecraft’s creation but Boe is a native to them. This is a polar inversion of most Lovecraft protagonists who suddenly find themselves thrust into a strange and frightening land. For Boe the dream lands are not weird, they’re home. The dream lands are not strange and though they’re sometimes frightening she has the wits and wisdom to navigate the horrors.

“She had never met a woman from the waking world. Once she asked Carter about it. ‘Women don’t dream large dreams,’ he had said, dismissively. ‘It’s all babies and housework. Tiny dreams.’

Men said stupid things all the time, and it was perhaps no surprise that men of the waking world might do so as well, yet she was disappointed in Carter. Her dreams were large, of trains a mile long and ships that climbed to the stars, of learning the languages of squids and slime-molds, of crossing a chessboard the size of a city. That night and for years afterward, she had envisioned another dream land, built from the imaginings of powerful women dreamers. Perhaps it would have fewer gods, she thought as she watched the moon vanish over the horizon, leaving her in the darkness of the ninety-seven stars.”

In The Dream-Quest of Villett Boe, misogyny is rampant. In typical fashion the men bust out women-doubting tropes left and right; Boe is told to stop asking questions repeatedly, the men might shut down the Women’s College if Jurat cannot be returned, the waking-world men fail to acknowledge the interior lives of the women who are considered inconsequential to their own quests, and importantly the women have internalized and abide by these norms even with their hearts and minds in rebellion. However, Villett Boe’s young life and new adventure stand in quiet defiance of this misogyny. The terrors of the dream lands are the terrors of men. Villette Boe has repeatedly survived contact with these monsters in her youth and abandons her comfortable life to go back for more. She is kind of an old-school hero; long-suffering, smart, doesn’t make mistakes, and her setbacks are due to the difficulty of the task rather than her lack of preparation. She is the embodiment of female competence and bravery. This is what makes Villett Boe and her creator Kij Johnson worthy of their Hugo Nomination. Good luck!