Cosplay, Capitalism and the Enthusiasm Market

by Theodore McCombs

The X-Men's Nightcrawler (Denver Comic Con 2016)

Lady Loki (Denver Comic Con 2016)

Donald the Hutt (Denver Comic Con 2016)

More than any feature of Comic Con, cosplay — character roleplay defined by ambitious, and usually amateur costuming — is the perfect public expression of fandom. Cosplay is the tension between the limitless enthusiasm of a fan and constrained means, resolved (for better or worse) by her creativity: very few people have the costume and makeup budget of the most shoestring movie or show; cosplaying cartoon characters is always an exercise in falling beautifully short.

I wish I had the space to share all my favorites from Denver Comic Con this year, but my running favorite, from last year's Con, still stands out in all his terrible glory: Grayskull Skeletor, from the 1987 Masters of the Universe movie.

Masters of the Universe is a highlight among pleasantly bad 80s fantasy movies. The cast is bizarre: Dolph Lundgren, hot off his wordless Rocky IV performance, as the heroic muscle toy He-Man; Frank Langella as wicked space wizard Skeletor; a pre-Friends Courtney Cox as Girl Who Makes Bad Decisions for Sake of Plot. The story, the effects, and the action are, at best, shabby and lovable. Meg Foster is a vision, and Langella owns every scene. Its schlockiness, at times, touches the sublime.

Skeletor HAS THE POWER... and a cute tote with gifts from our sponsors.

Meg Foster as Evil Lyn (via Wikipedia)

The backstory to the movie’s making is a perfect storm of suck, and Slashfilm’s oral history of the movie’s production is well worth a read in full. The director’s only credit of note was Conan the Barbarian — no, no, not the movie, the Universal Studios live show. The film studio Cannon was months away from bankruptcy. The budget kept shrinking, Dolph Lundgren barely spoke English, and also it was from the beginning a pretty thin idea. Because it all started in the capitalist muck of Mattel’s product line development: He-Man and the Masters of the Universe was a desperate but brilliant effort to compete with the Star Wars action figures by jury-rigging a fantasy universe that appealed to boys. The Saturday morning cartoon was a mercenary but wildly successful stab at synergistic marketing, and the film similarly aimed to drive up sales with a Star Wars-like cinema event: it just had the bad luck to arrive after interest had peaked.

He-Man was conceived as a pure, naked commodity, a way to monetize masculinity fantasies and sell patriarchy to itself. I loved it. I meticulously collected all the bulb-chested action figures and — though I was confused by how different the film was from the canon established in the toy comics and cartoon — I assumed the producers must have known what they were doing, and accepted the spectacle. (And though the producers assuredly did not know what they were doing, I also was content to accept Dolph Lundgren as a naked commodity.)

After bankruptcy, the production studio reorganized into The Cheesecake Factory. (GIF by He-Man Reviewed.)

Skeletor’s transfiguration with the power of Grayskull is the gaudy, bonkers aesthetic climax of the film, an inspired moment in a deeply uninspired piece of art, and to see, at Comic Con, a fan reclaim that moment is itself inspiring. The Masters of the Universe universe was born in greed and died in greed, but it provided a vehicle for our imaginations. From muck of corporate forces trying to conjure and profit off our enthusiasm, we fished out a genuine enthusiasm and, nearly thirty years later, some guy made a work of art out of it.

I think it’s that same resilient enthusiasm that drives speculative “commercial” fiction. As Catie remarked last week about YA dystopias, the fact that cynical market forces have slobbered over our toys doesn’t dampen our enthusiasm for those stories, if they help us relate to the world. Cosplay is a way to reclaim the emotion of art from the schlock, to affirm what we love among the commercial realities that hardly deserve our tolerance. The same instinct crosses over into fiction: we find what we love where we find it, and once we take it from the corporate bobbleheads who slapped it together, it’s ours for good.

Voyage to the Bottom of the Comic Con Literary Track

by Sean Cassity

I’d swear it was a secret, parallel convention hidden within Denver Comic Con if the panel rooms weren’t so large and so densely packed with fans. It is not the aspect of any comic con that gets any real attention. It’s not the cosplayers, who are unavoidable, ready to begin astounding you even as you search for the end of the line that can seem only reluctantly, eventually, to let you in. It’s not the show floor where numerous vendors with loud booths eager to sell your fandom back to you guard the path, and where you must trek deep into the hall to find the creators of the things you love sitting at sparse tables, often unattended by the very fans whose awe they have inspired. No, if you pierce the bannered celebration of comics and movies and tv shows and cartoons, if you flip past the ads in your program and you know what you’re looking for, you can find panels in nondescript back rooms where Authors talk about Books. These are the rooms where I spend 80% of my time at any comic con I attend.

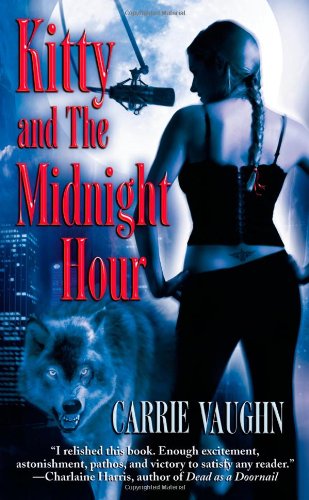

More werewolves with Stephen Graham Jones's Mongrels

As clever as people feel presaging the end of reading in the television age, the MTV age, the internet age, the Twitter and SnapChat age, at 1 pm on an afternoon in Denver, I shared a room with hundreds of people who stepped from a bacchanal of easily inhaled media to listen to a panel called “The Writing Process of Best Sellers.” None of us expected to leave this 50 minute panel armed to knock Nicholas Sparks off his smarmy little throne. We knew we’d hear answers to questions about writing routines. We knew all the panelists would recount how many bad stories they wrote before their first good one. But we wanted to commune with the authors because we had been affected by their books. We wanted to peek into the black box of authorship, even if the box still contained the same advice that was in there the last time we peeked. It was still pleasant to hear it phrased in different way. In a world of insecurity where we fret our last Facebook comment about fracking may have just cost us the love of a high school acquaintance we haven’t seen in 15 years, it’s reassuring to hear Terry Brooks confess he didn’t dare to quit his day job for nine years after his Shannara books had already sold millions of copies or that Carrie Vaughn, when she worries to her mother that this is the Kitty the werewolf novel that is going to sink her career, gets reassured she had said the exact same thing about her last four novels.

While that panel may have been full, the next author panel in the same room, “The Art of the Complex Villain,” featuring Stephen Graham Jones and Molly Tanzer, among others, was even more crowded.

Since that weekend my writing is just as likely or unlikely to be best seller material. And, yes, my villains are still the heroes of their own story. It’s not craft altering epiphanies I expect out of author panels at a comic con. But it is an opportunity to sit in an audience of other readers and with our numbers confirm that no matter how much passive media we pour out of screens and into our pupils, the interactive, imagination-engaging experience of reading maintains a high altar in the temple of our fandom.

In the crucible of catastrophe, we learn deeper truths about love, loyalty, and compassion.