In the third and final entry in our Xenogenesis appreciation, Gemma Webster and Theodore McCombs talk Imago (1989), Octavia Butler’s conclusion to the trilogy. The first book, Dawn, followed Lilith Iyapo’s captivity with the Oankali, an alien race of tentacled, insatiably curious genetic engineers who go planet to planet seeking out new life to collect and, on occasion, form new species with through interbreeding. This is their plan for humanity, whom they’ve just salvaged from nuclear apocalypse.

Lilith helps her fellow human survivors escape the Oankali, and by the second book, Adulthood Rites, these “resister” villages are widespread. But the Oankali have made humans sterile, able to reproduce only with Oankali mates, because they fear the “human contradiction”: that fatal combination of intelligence and hierarchical behavior that led to humanity’s near self-destruction in the first place. The resisters resort to stealing the new Oankali-human “construct” children like Akin, Lilith’s son. As Akin comes to know his human captors, he advocates for the resisters and convinces the Oankali to establish a colony of pure, fertile humans on Mars.

Imago picks up several years later, with the first construct ooloi, Lilith’s child Jodahs. Oankali have three sexes: male, female, and ooloi (“it”). These ooloi are natural genetic manipulators, able to cure genetic diseases or enhance strength with a touch. They are essential to Oankali reproduction, the chefs who combine their mates’ genetic ingredients into a soufflé baby. And they are mindblowingly good lays. Ooloi give their mates such transcendent pleasure, it seduces them into a sort of biochemical dependence. But Jodahs is a dangerous unknown. As a construct, it wields humanity’s “gift” of cancer, which it uses to change shape or regrow limbs; but it can also create deformities and plague through sheer carelessness. What will Jodahs become? The triumph of Oankali-human union—or the grisly failure of Lilith’s brood?

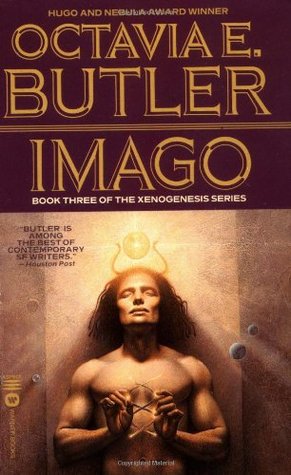

A very masculine version of Jodahs the ooloi construct

Theodore McCombs: Let’s talk about sex and structure in the Xenogenesis trilogy (baby). Butler seems to want us to notice how the trilogy tracks the Oankali triad of sexes. Dawn followed Lilith, a human woman; Adulthood Rites is the coming-of-age story of the first construct male. And Imago features an ooloi’s point of view, at last.

Arguably, Dawn and Adulthood Rites are ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ books: Dawn is a sort of space-Gothic novel, about a captive heroine using her wits and resourcefulness to navigate her captors’ control of her; Adulthood Rites is a very familiar story of a young man finding his place in the world. How is Imago a more ‘ooloi-ine’ book?

Gemma Webster: In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf made a case in support of Coleridge's assertion, “The truth is a great mind must be androgynous.” Woolf posits that perhaps Coleridge

meant that the androgynous mind is resonant and porous; that it transmits emotion without impediment; that it is naturally creative, incandescent and undivided.

Woolf suggests that the purely masculine or purely feminine mind cannot create: just as in biology, male and female must mix together to procreate, in the creative mind, masculine and feminine must combine in a single person. In the Xenogenesis series, similarly, the ooloi is a necessary intermediary in the procreative process. Interestingly, both of the preceding books in the series are written in third person and Imago is written in the first person. It is a much more emotional story.

TM: It’s intriguing to think about how we would have read an ooloi narrative in close third person, always dealing with that ‘it’ pronoun. I think it would have been so jarring and distancing.

GW: Giving us that close-in experience with the "androgynous" point of view was for me particularly germane to the writing experience. The writer is always having to embody characters of every gender (in this case, a third gender). But just like Woolf says, the writer's mind has to have both masculine and feminine intertwined for the creation of the piece itself. The dynamic between the creating process and biological creation really came together for me in the third book.

The novel, as a form, is also necessarily about leaving the status quo. Stories have their inciting incident and conflict; nature refuses to be static. That first-person point of view puts us right in the discomfort of both of those situations.

TM: And I think that bears out across the trilogy, in that one of its stronger through-lines is this idea of resistance: Lilith’s desire to escape the Oankali and spoil their plan; Akin’s rebellion and his endorsement of the resister project. The protagonist chafes against the world that's been set up around them, trying to assimilate her or him. But what status quo, exactly, is Jodahs fighting? Maybe the most unsettling thing for Jodahs is that it's responsible for fashioning that new normal.

Of course, there are major resister characters in Imago, but there wasn’t any big, trilogy-capping finale to the resistance. The Mars colony is still out there, I suppose, but as soon as the Earth-based resisters meet Jodahs, they basically throw up their hands. Jodahs is so damn alluring, they give up resistance. Resolution through sexiness. Not what I would have expected.

GW: I think that theme of the ooloi's sexual allure, across all three books, shows that the Oankali demand more than assimilation from their trading partners. They acquire their genes and they modify them so that there is no return (without benevolent ooloi permission). Jodahs is the evolved ooloi, even sexier than the previous generation. The chemical bonds of sex and family and love even, have become an even tighter trap for humans.

TM: Captivity is another through-line for the trilogy: Lilith is captive (sort of) on the Oankali ship, and Akin is kidnapped by the resister village, but Jodahs, here, plays the captor with its human mates. It omits some vital information as they help it through its critical metamorphosis: that they will be chemically bonded to it once it reaches adulthood, and will never quite be able to live without it.

GW: And Lilith lets it do it! (The "it" pronoun really does get cumbersome.)

TM: Exactly—she’s come disturbingly far from her initial position of subverting the Oankali plan. Although cast as humanity’s “Judas goat” in Dawn, she really was trying to help the resistance by being practical and strategic. Now she really has betrayed full humans, all to protect her kid. Her kid whose name bears a striking resemblance to that famous biblical traitor, incidentally.

The Spanish version went with the really alien concept for Jodahs.

GW: Lilith gets a nice moment of ambivalence in this book, one of her best. Her past self (the prisoner/rebel in Dawn) collides with the new self (the "collaborator" and mother to so many construct children). Her decision to silently betray Jodahs's human mates carries real weight, even though it happens quickly on the page. It felt really human and complex. We see that her hierarchical behavior has been re-ordered rather than removed. It brings us back to the question, What is freedom, when the body can be compelled? Her chemical dependence on her ooloi mate Nikanj is one compulsion, but it isn't the reason for her decision. Is motherhood the next level of the trap?

Lilith's choice is just one example of how this book combines the family drama set in the world of the space opera. That gives this story a deeper intimacy than the preceding books; narrowing down instead of encapsulating the trilogy.

TM: That's a really interesting choice on Butler's part. The act of what to write about in a novel is a political choice, after all: You are declaring that this character, these themes, are deserving of the reader’s attention. Does this shift, from the vast reach of Dawn and Adulthood Rites to Imago’s intimate family drama, reflect some comment by Butler on the individual’s place in these huge events? Lilith and Akin are both figures of almost messianic-level importance to these two species’ destiny; so is Jodahs, but we see far more of it coming to understand itself—another coming-of-age story—instead of its impact on the Oankali-human project.

GW: Hence the title Imago. In entomology, "imago" is the last stage of insect morphology. Jung used the the term to refer to the personality's formation through identification with the collective unconscious. Physical maturity and psychological connection/empathy are the end results of the coming-of-age story.

The end of each of these stories is a return to the conquering/empowered system. The co-evolution of the species is unavoidable. It is natural and appealing (chemically if not otherwise) to both humans and Oankali. Only those on the Mars colony have opted out. There is a sense of inevitable doom for their future as well. The hope actually sort of appears to be something in the middle. A sort of rebellion within the system, a merging and modifying rather than a reversion. As the combined entity of everything that is good and bad from human and Oankali, Jodahs gets to become the creator of its own town/ship/family. My final takeaway is, start locally to create new worlds.

Read Similar Stories

Need some book recommendations for Valentine's Day? Well, frak, don't ask us.