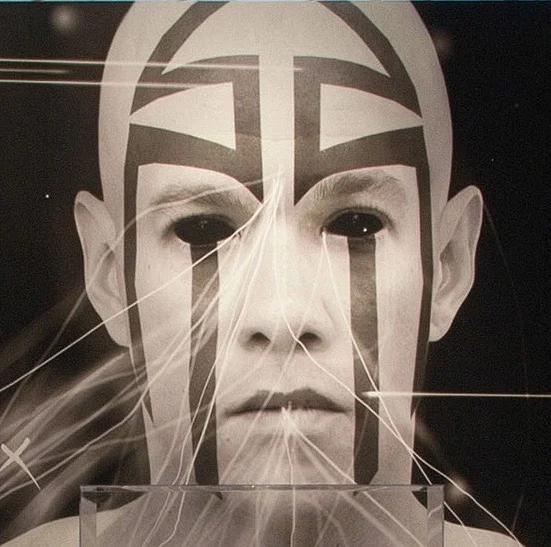

Author Peng Shepherd (photo credit: Rachel Crittenden)

In Peng Shepherd’s The Book of M, the apocalypse just makes things worse. Post-apocalyptic fiction from The Road to The Walking Dead often toys with a sort of brutal, atavistic fantasy of the complicated world dropping off, leaving the survivors completely, terribly independent. In this form of the genre, the nuclear cataclysm, pandemic, or zombie plague shatters the intricate economies that connect us, so that our hero carries out his simpler man v. man or man v. nature plot more as an individual, less as a citizen. It’s American as apple pie, really. But in The Book of M, the apocalypse binds the survivors to each other in an even more terrible, bewildering interdependence, shattering our fantasies of the individual.

It all starts in a Pune spice market, where an Indian man inexplicably loses his shadow. Soon, people all over the world start losing their shadows. Even more inexplicably, the shadowless start forgetting things like their family or their identities—then even more fundamental things, like how to read, or their need to eat, until their minds are completely erased. As the Forgetting plunges the world into chaos, Orlando “Ory” Zhang and his wife, Max, hole up in an abandoned hotel in the Virginia woods, sticking it out in classic survivalist mode. Until one day, Max loses her shadow.

What are we without our memories? According to Shepherd, not a whole lot, and anyone who’s seen a loved one through dementia will recognize the agony and fear watching a person slowly vanish. And if identity owes so much to memory, then, by The Book of M’s rules, we hang from our shadows as much as they hang from us. Shepherd’s most uncanny set pieces explore the disorientation of dependency, of discovering your true center of gravity is outside your body. At one point, Max, speaking into the tape recorder Ory has given her to save her memories, encounters a painted shadow on the cement:

A shadow, and no person. It looks even stranger than a person with no shadow. I stood above it, in the exact same position—one arm raised as if talking, the other on my hip—and stared. I stood there for hours like that. … It was eerie, like putting on clothes that aren’t yours, or going with it when someone at a crowded party mishears your name and calls you something slightly different for the rest of the loud, buzzing night.

That sense of dependency deepens as we come to appreciate the final piece of the Forgetting: when the shadowless forget, sometimes they alter reality according to that misunderstanding. When patient zero forgets the Pune spice market, the whole thing disappears—stalls, shoppers, and all. A shotgun shoots literal lightning storms into men’s chests, because some shadowless forgot what guns do. So Max takes off, fleeing their hideout while Ory is out scavenging: she can’t take the risk of forgetting Ory out of existence.

John Tenniel, “The Red King asleep,” in Through the Looking-Glass.

Heartbroken and determined to stay together, Ory mistakenly pursues Max to nearby Washington, D.C., which has become a warzone between shadowed and shadowless survivors. The shadowless are led by an ogre-like shadowless called the Red King, whose last, potent shred of memory—something to do with books—serves as an idée fixe uniting his army. The reference is to an episode in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, in which Tweedledee and Tweedledum show Alice the sleeping Red King, claiming she is a figment of his dream. Alice is upset, naturally, and Shepherd’s apocalypse subtly elaborates Alice’s distress into a literally nightmarish dependency, in which the shadowed survivors are living through the bad dreams of the shadowless’s superpowered imaginations. It’s a timely reflection of today’s political climate, which can often feel like we’re living out someone else’s nightmare.

The Red King isn’t Shepherd’s only apt literary allusion: in the long-shot hope of a cure, Max sets off for New Orleans with a band of shadowless led by Ursula, who I’ve decided is just who Ms. Le Guin herself would be in the apocalypse, complete with rifle, RV, and buzzcut. (Ursula Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven featured similar reality-revising powers on a more intimate, but still unsettling scale.) The chapters of Max, Ursula, and the others fighting to hold their destination ahead, even as they’re doomed to forget where they’re going, are riveting, fresh adventure in an often stale genre, and a deeply emotional read.

Zero Shadow Day in India, when the sun’s exact alignment causes vertical objects to cast no shadow. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons.)

Recently, I was talking genre with Clarion friend and casual genius Sanjena Sathian, and she suggested the following rule: the difference between speculative fiction’s “literary” or “genre” pedigree has less to do with quality of writing and is more about how the speculative element is organized into a logic. If the logic is scientific, it’s science fiction; if it’s a magical system, it’s fantasy. Literary fiction systematizes its unreal elements less, but they sometimes follow a sort of mythic logic (magical realism), or maybe a dream logic (absurdism). Ironically, this means “genre” speculative fiction has more realism, in that its characters will generally interact with the unreal element the way people really would—with awe, horror, indifference, depending on the world-building—while “literary” speculative fiction can’t afford that kind of naturalism, since it would break the dreamy poetry.

The Book of M, though, puts down realistic characters in an absurdist universe. When our heroes talk to wolves or watch a living Statue of Liberty leveling New York City, they react not with the lyrical ennui of a Murakami character but with the oh-shit confusion and fear the situation demands. If it’s one thing we have confirmed from the last two years, it’s that absurdism is downright terrifying to live through. And if M’s magical system is at times clunky, that’s part of the novel’s impact. When the apocalypse comes, Shepherd seems to say, it won’t be brutally simple: it’ll be as complex, incomprehensible, and out of our hands as our present prosperity is.

And yet, there is a sort of dream logic to shadows and memory: each of these involves a flattening. The shadow is a two-dimensional projection of a three-dimensional figure. The memory is only a one-sided, partial narrative of the thing in itself. I wish I could gush more about this—without spoilers, I’ll say only that Shepherd makes this idea pay off with the end of Max and Ory’s story, both a satisfying, emotional denouement and a formally brilliant coup de théâtre.

The Book of M is Peng Shepherd’s début novel and is out in hardcover now. It’s a mature, compelling adventure that keeps the apocalypse fresh, even as our own overtakes us.

In a world on the brink of collapse, a quest to save the future, one defeat at a time.